No one was more surprised than he when the little automaton gentleman dressed in Deuteronomy green who had sounded the time for Desolation Road defied his time-frozen mechanics to waltz out and strike the bronze bell with his little mallet. On the last note of the fifteen the little man seized arthritically forever and two pairs of high-heeled hand-tooled leather gaucho boots kicked up the dust and turned toes toward Mr. Jericho’s battered brogues.

“Formal rules?”

“Formal rules.”

“No poisons?”

“No poisons.”

“Might as well begin then.” And two steel needles kicked puffs of dried whitewash out of the wall at the end of the street.

—My but they’re quick! Mr. Jericho crawled out of the far side of the veranda under which he had rolled and looked for cover. A needle grazed his left earlobe and buried itself in the warped wooden planking of the veranda.-Fast, very fast, too fast for an old man? Mr. Jericho jumped behind a low wall and squeezed his first needle off at the snake-quick figure in black silk that had fire on him.-Run run run! the Exalted Ancestors shouted, and he ran ran ran just as a string of needles pitted and cracked the white plasterwork where he had been crouching.-Always remember there are two of them, the limbosouls told him.

—I’m not about to forget it, he told them, and rolled and fired all in one cat-graceful action. The needle howled wide of the black-hatted figure diving down from the roof.

—One in the street, one in the alley. They’ve got you running. You get them running. You built this town with your own hands, you know it. Use that knowledge. The Ancestors were dogmatic. Mr. Jericho zigzagged down Alimantando Street toward the timelost patch of jungle vinery and drew a stitching of needles closer and closer to his twinkling heels. He leaped for the veranda of the Pentecost sisters’ General Merchandise Store and the last needle embedded itself in his footprint.

—They are good. A perfect team. What one sees, the other sees, what one knows the other knows. He consciously brought his breathing under discipline in the Harmonic Mode and let his Ancestors kick him into the sensory state of the Damantine Praxis. Mr. Jericho closed his eyes and heard dust motes fall in the street. He took a deep breath through his nostrils, tagged a stench of hot tense sweat, popped up at a window, and pumped off two needles.

—Knowledge. An unbidden memory, demanding as unbidden memories always are, bubbled to the front of his head: Paternoster Augustine’s garden; a pergola amid trees and singing birds, velvet-smooth grass beneath feet, the scent of thyme and jasmine in the air, above his head the mottled opal of Motherworld.

“Learn all you can,” said Paternoster Augustine seated in a lepidoptiary of rare fritilliaries. “Knowledge is power. This is no riddle, but a true saying and much to to be trusted. Knowledge is power.”

—Knowledge is power, repeated the massed choir of all souls. What do you know about your enemies that will give you power over them? They are identical clones. They have been reared in identical environments so that they have developed the same responses to the same stimuli and thus can be considered to be one person in two bodies.

That was the sum total of his knowledge of AlphaJohn and BetaJohn. And now Mr. Jericho knew how to beat them.

A shadow squeezed off a needle from behind a pump gantry. Mr. Jericho shifted his head the moment he sensed the metal latticework cool in the man’s shadow. He slipped from the General Merchandise Store veranda, crept tigerman through the jungle vines, and made a low fast run through the maize fields for his destination. The solar power plant. Mr. Jericho crawled soily-bellied through the geometrical domain of reflections and held his antique needle-pistol pressed close to his chest. He smiled a thin smile. Let the smart boys come hunting him here. He waited as an old, dry black spider waits for flies. And they came, cautiously advancing through the field of angled mirrors, starting at reflections and flibbertigibbets of the light. Mr. Jericho closed his eyes and let his ears and nose guide. He could hear the heliotropic motors shifting the lozenges to track the sun; he could hear water gurgling through black plastic pipes; he could hear the sounds and smell the smells of confusion as the clones in the mirror-maze found themselves cloned. Mr. Jericho heard AlphaJohn wheel and fire at the looming shape rearing up behind him. He heard the glass crack into a spiderweb of fissures, the reflection shot through the heart. There was quiet for a while and he knew that the Johns were conferring, ascertaining each other’s position so they would not fire on each other. Telepathic conference done, the hunt resumed. Mr. Jericho rose to the crouch and listened.

He heard footfalls on soft red dust, footfalls approaching. He could tell that the target’s back was momentarily turned by the sound his heels made on the earth. Mr. Jericho smelled human sweat. A clone was entering the row of mirrors. Mr. Jericho squeezed his eyes tight shut, stood up, and fired twohanded.

The needle took AlphaJohn (or maybe BetaJohn, the distinction was trivial) clean between the eyes. A tiny red caste-mark appeared on his brow. The clone emitted a curious squawk and slipped to the ground. An echoing, answering wail came up from the depths of the mirror-maze and Mr. Jericho felt a glow of satisfaction as he loped through the rows of reflectors toward the cry. The twin had shared his clone-brother’s death. He had felt the needle slip into his forebrain and rive away light life love, for they were one person in two bodies. As Mr. Jericho and his Exalted Ancestors had surmised, Mr. Jericho found the brother gasping on the ground, eyes gazing at the high arch of heaven. A little stigmata of expressed blood sat on his forehead.

“Shouldn’t have given me the chance,” said Mr. Jericho, and he shot him through the left eye. “Punks.”

Then he returned to the Bar/Hotel, where the man in Deuteronomy green had frozen in commemoration of the last gunfight. He went up to the bar and told Kaan Mandella to drop whatever he was doing, pack all his wordly possessions, and come with him that very hour to the important places of the world, where together they would regain all the power and prestige and transplanetary might that had been Paternoster Jericho’s.

“If that was their best, they are no match for this old man, none of them. They have gone soft over the years, while the desert has made me old and hard, like a tree root.”

“Why me?” asked Kaan Mandella, head swirling whirling with the unexpectedness of it all.

“Because you are your father’s son,” said Mr. Jericho. “You are marked with the family curse of rationalism as Limaal was before you, I can see it, smell it, down there beneath the dollars-and-centavos business nose, deep down there you want order and power and an answer to every question and in the place where we are going that is going to be a very useful skill. So, are you coming with me?”

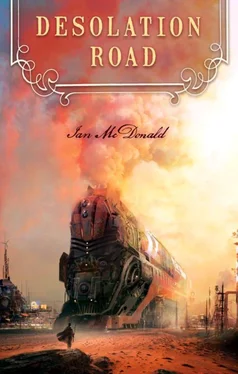

“Sure. Why not?” said Kaan Mandella with a grin, and that very afternoon the two of them, armed only with an antique manbone-handled needlepistol, successfully held up and hijacked the 14:14 Ares Express and rode it into Belladonna’s Bram Tchaikovsky Station and a destiny as glorious as it was terrible.

68

Now that the final summer had come, Eva Mandella liked to work outdoors under the shade of an umbrella tree by the front door of her rambling home. She liked to smile and talk to strangers, but she was now so incredibly ancient that she no longer dwelled in the Desolation Road of the 14th Decade but rather in a Desolation Road peopled with and largely constructed from the memories of every decade since the world was invented. Many of the strangers she smiled and talked to were therefore memories, as were the pilgrims and tourists for whom she still laid out every morning her hand-woven hangings worked with the traditional (traditional in that she had invented it and it was curious to her times and place) designs of condors, llamas and little men and women holding hands. Sometimes, rarely, there would be the clunk of dollars and centavos in her money-box, and Eva Mandella would look up from her tapestry loom and remember the day, month, year and decade. Out of gratitude for having drawn her back to the 14th Decade, or possibly out of denial of it, she would always refund the money to the curiosity-seeking tourists who bought her weavings. Then she would resume her conversation with the unseen guests. One afternoon in early August a stranger came and asked her, “This is the Mandella house, is it not?”

Читать дальше