“Thirty-seven frames,” said Casper Milquetoast, the obiman. Side bets were not discussed. They were not important. The stake was the title of the Greatest Snooker Player the Universe Had Ever Known. Limaal Mandella won the toss and broke off to begin the first of the thirty-seven frames. As he had so correctly surmised years before when Trick-Shot O’Rourke had shown him the destiny he had refused to accept, snooker was the supreme game of rationalism. But the Anagnosta Gabriel was rationalism incarnate. To its superconducting soul the balls on the table were no different from the ballet of orbital technology ranging from grape-sized monitors to habitats tens of kilometres across, all of which it routinely choreographed. Behind Casper Milquetoast’s every cue action a tiny fragment of that computive power made precise calculations of spin, impulse and momentum. “Luck” had no analogue in the glossolalia of the Anagnostas. Always before, there had been the lucky fluke, the chance mistake by an opponent that put Limaal Mandella in a framewinning position; the accumulated run of misfortune that demoralized the enemy into self-defeat, but computers do not demoralize and they do not make mistakes. Limaal Mandella had always maintained that skill would always defeat luck. Now he was being proved correct.

In the midsession break (for even obimen must eat, drink and urinate) Glenn Miller drew Limaal Mandella aside and whispered to him, “You made some mistakes there. Bad luck.”

Limaal Mandella flew into a temper and pushed his sweating face close to the jazz musician.

“Don’t say that, never say that, never let me hear that again. You make your own luck, you understand? Luck is skill.” He released the shaken bandleader, ashamed and frightened at how high the tide of irrationality had risen around him. Limaal Mandella never lost his temper, he told himself. That was what the legends said. Limaal Mandella hid his soul. But his outburst had shamed and demoralized him and when play resumed the Anagnosta Gabriel capitalized on his every mistake. He was outrationalized. As he sat in his chair automatically wiping his cue while Casper Milquetoast’s computerguided hands built break after break, he learned how it felt to play himself. It felt like a great boulder rolling up and crushing him. That was how he had made others feel: crucified on their own self-hate. He hated the self-hatred he had summoned up in the countless opponents he had defeated. It was a dreadful, grinding, gnawing thing which ate the soul away. Limaal Mandella learned remorse in his quiet corner, and the self-hatred ate away at his power.

His hands were numb and stupid, his eyes dry as two desert stones; he could not hit the balls. “Limaal Mandella is losing, Limaal Mandella is losing": the word spiralled out from Glenn Miller’s Jazz Bar through the streets and alleys of Belladonna and behind it came a silence so profound that the click and the clack of the balls carried through the ventilators into every part of the city.

The computer ground him fine as sand. There was no pity, no quarter. Play would continue until victory was assured. Limaal Mandella lost frame after frame. He began to concede frames which with determination he might have won.

“What’s wrong, man?” asked Glenn Miller, not understanding his protege’s agony. Limaal Mandella returned in silence to the table. He was being destroyed before the spectators’ gaze. He could not bear to look up and see Santa Ekatrina watching. Even his enemies ached for him.

Then it was over. The last ball was down. ROTECH Anagnosta Gabriel operating through the synapses of the condemned murderer was the Greatest Snooker Player the Universe Had Ever Known. City and world hailed him. Limaal Mandella sat in his chair shot with his own gun. Santa Ekatrina knelt to take him in her arms. Limaal Mandella stared ahead of him, seeing nothing but the full tide of irrationality that had engulfed him.

“I’m going back,” he said. “I can’t stay here; not with the shame around me every minute of every day. Back. Home.”

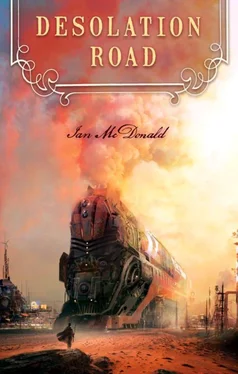

Five days later he snapped all his cues in half and burned them. On top of the fire he threw his contract with Glenn Miller. Then he took his wife, his sons, his bags, his baggage and as much money as he could bear the sight of and with that black money bought four tickets on the next train to Desolation Road.

At Bram Tchaikovsky Siation porters scratched at his coat-tails. “Carry your bags, Mr. Mandella, sir, please, carry your bags? Sir, Mr. Mandella, carry your bags?” He loaded the luggage onto the train. As it passed out from under the immense mosaicked dome of Bram Tchaikovsky Station, goondahs, gutter boys and urchins too poor for even a third class bench dropped from the signal gantries onto the roof. They leaned over and banged on the compartment windows, calling, “For the love of God, Mr. Mandella, let us in, kind sir, good sir, please let us in, Mr. Mandella, for the love of God, let us in!”

Limaal Mandella pulled the blinds, called the guard, and after the first stop at Cathedral Oaks there were no further disturbances.

35

The cylinder of rolled documents hung from Mikal Margolis’s shoulder twenty-five centimetres above the track. Mikal Margolis hung from the underside of a Bethlehem Ares Railroad Mark 12 air-conditioned first class carriage. The Bethlehem Ares Railroad Mark 12 air-conditioned first class carriage hung from the underside of Nova Columbia and Nova Columbia hung from the backside of the world as it circled the sun at two million kilometres per hour, carrying Nova Columbia, railroad, carriage, Mikal Margolis and document cylinder with it.

Ishiwara junction was half a world away. His arms were tough now, they could carry him all the world’s way around the sun hanging from the undersides of trains. He no longer felt the pain, of arms and Ishiwara Junction. He was beginning to suspect that he had a selective memory. Hanging beneath trains gave him much time for thought and self-examination. On the first such occasion after Ishiwara junction he had devised the scheme that had drawn him down the shining rails across junctions, switchovers, points, ramps and midnight marshalling yards toward the city of Kershaw. There was an irresistible attraction of dark for dark. The roll of papers across his shoulders would not permit him any other destiny.

He shifted to the least uncomfortable position and tried to picture the city of Kershaw. His imagination filled the great black cube with cavernous shopping malls where the exquisite artifacts of a thousand workshops commanded eye and purse; level upon level of recreation centres where every whim could be indulged from games of Go in secluded tea houses to concertos by the world’s greatest Sinfonia to basements filled with glycerine and soft rubber. There would be museums and auditoria, Bohemian artists’ quarters, a thousand restaurants representing the world’s thousand gastronomies and covered parks so cleverly designed you could believe you were walking under open sky.

He could see the clanging foundries where the proud locomotives of the Bethlehem Ares Railroad Company were constructed, and the Central Depot from which they were dispatched all across the northern half of the world and the subterranean chemical plants that bubbled their effluent into the lake of Syss and the factory-farms where strains of artificial bacteria were skimmed from tanks of sewage to be processed into the thousand restaurants’ thousand cuisines. He thought of the rainfall traps and the brilliantly economical systems of water reclamation and purification, he thought of the air shafts up which perpetual hurricanes spiralled, the dirty breath of two million Shareholders exhaled into the atmosphere. He imagined the outer skin penthouses of the managerial castes, their views of Syss and its grimy shore increasingly panoramic with altitude, and the apartments in the quiet family residential districts opening onto bright and breezy light-wells. He thought of the children, happy and well-scrubbed, in the Company schools learning the joyful lessons of industrial feudalism, which was not hard for them, he thought, for they were surrounded every second of every day by its pinnacle of achievement. Suspended beneath the first class section of the Nova Columbia Night Service, Mikal Margolis beheld the whole of the works of the Bethlehem Ares Corporation in his soul-eye and cried aloud, “Well, Kershaw, here I am!”

Читать дальше