Be patient with me , she thought.

Metzler was a good man. He acted as if he’d heard her say it. Maybe her anxiety showed in her eyes. He linked his pad to the wall display and said, “Look at this,” drawing everyone’s attention away from Vonnie.

Four days ago, ESA Probes 112 and 113 had stolen into a branch of catacombs occupied by the smaller breed of sunfish. Each probe carried a dozen spies with it, like beetles clinging to its top, because spies weren’t capable of covering as much ground as probes yet were better suited for surveillance.

Spreading through the ice and rock, patiently forming themselves into a dish-like array, the spies had watched the sunfish for fifty-two hours before Probes 112 and 113 emerged from hiding.

Technically, it wasn’t Second Contact. The Americans had pursued two groups of sunfish into the ice. They’d also reported more carvings, fungus, bacterial mats, and eel-like fish in a cavern half-flooded by a fresh water sea. More startling, the Americans had also found a vein of shells and dirt suspended in the ice with the corpse of what appeared to be a warm-blooded, shell-eating creature like a ferret. The corpse had been ravaged by compression, but it was unquestionably a fur-bearing animal — an eight-legged thing with beaver-like teeth, talons, and an elongated body made for burrowing and climbing.

If the Chinese were having similar success, they’d made no announcements. Vonnie thought the Brazilians must have encountered sunfish even if their focus had turned to destroying Lam. The FNEE mecha were too deep. At the very least, they must have found carvings or ruins.

In both of their encounters, NASA’s probes had been attacked. The first time, NASA rolled its mecha into balls, meekly accepting the sunfishes’ beatings. That had cost them every probe in the scout team, which they deemed an acceptable loss. Vonnie fretted it sent the wrong message. She’d told a NASA biologist that now the sunfish thought their metal doppelgangers were easy prey. “No,” the biologist said. “Now they know the probes are inedible and nonaggressive. Next time they might accept us.”

The next time, the sunfish had dropped three tons of rock on NASA’s probes before swarming the sole survivor. Attempts to communicate via sonar and the sunfishes’ shaped-based language were ignored.

NASA had tagged four sunfish with nano darts, expecting to monitor the tribe with these beacons… but the sunfish tore open the infinitesimal holes in their skin, then bared their wounds to their comrades, who chewed into their flesh before regurgitating the gory meat. The biologists agreed the sunfish were extremely sensitive to parasites. That indicated a prevalence of other bugs or microorganisms as yet undiscovered. On Europa, it appeared, pests and disease were as virulent as the higher lifeforms. Contagion and blight might have done as much damage to the sunfish empire as volcanic upheavals.

“Here’s what’s driving me crazy,” Metzler said, opening a sim full of mathematics. Vonnie recognized some of the data as Lam’s.

“There’s not enough food in the biosphere for predators their size,” she said.

“Not by a third.”

“We know they’re omnivores. They could get a lot of the mass they need from vegetation.”

“What kind of vegetation? We haven’t found anything more advanced than fungi, and I don’t think we will. Not without photosynthesis. There won’t be anything like terrestrial plants or algae.”

“Maybe sunfish don’t need as many calories as we would if we were their size,” Ash said. “Couldn’t their intake be explained by a difference in Europan metabolism?”

“If they hibernated for extended periods, I’d say yes,” Metzler said, “but their genome doesn’t show protein expression patterns that resemble anything like hibernating species on Earth. The only behavior we’ve recorded has been sustained activity. They never stop. They don’t even sleep.”

“I’ve seen them rest,” Vonnie said, remembering the very first group of sunfish she’d met.

“That was in a low-atmosphere environment with almost zero oxygen,” Metzler said. “We think they were harvesting fungal spores from the rock. They were moving at half-speed to conserve their time in the area. Uh, they also might have bled one of their friends for the oxygen in his system.”

“What?”

“We’ve put together a few sims using your files. At the back of the crevice, it looks like they were holding down the smallest sunfish. They were drinking from him. Then he might have been dinner, too.”

“God.” Vonnie shook her head. “That would fit with their pack mentality, but you’re making a lot of assumptions.”

“Yeah. Presumably there are more diverse food chains further down, or the sunfish are farming somewhere we haven’t found yet, or both. It would be fantastic if we could get some mecha down to the ocean. A lot of our answers will be there.”

The ocean , Vonnie thought. “Have you asked Koebsch? There are soft spots on the equator where the ice is only five kilometers thick. We could drill through.”

“It’s under consideration. We already have our hands full.”

She smiled at the understatement. Earth had dispatched another high-gee launch loaded with new mecha and supplies, but the ship was piloted by an AI. They didn’t foresee adding more people soon. The costs were too steep.

“Tell me about Tom,” she said.

“Our star pupil.” Metzler opened a new file without playing it. “Listen, I should’ve warned you not to get your hopes up. What happened this morning was incremental at best.”

“You might get another kiss anyway.”

“Oh. Okay.”

“Would you two knock it off?” Ash said, but her tone was encouraging, and Vonnie was glad to be teased. Their friendship made the sunfish less intimidating.

She still had nightmares.

The emotions she felt toward the sunfish bordered on awe and reverence, but she still had bloody nightmares.

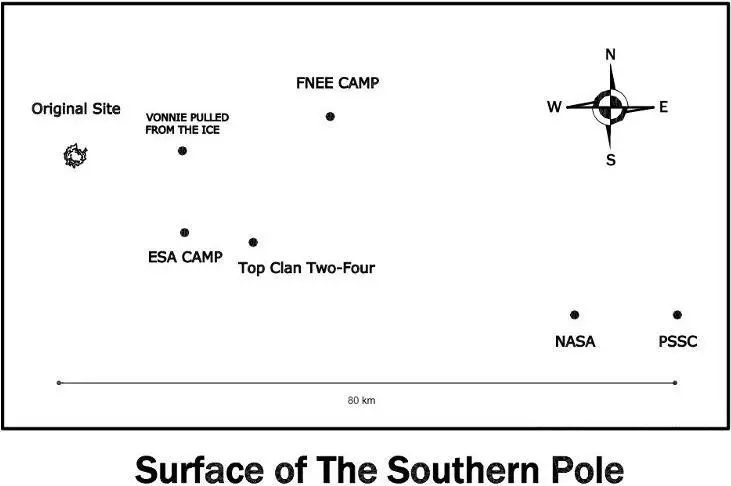

Surface of the Southern Pole Map

Constructed mostly of ceramics, ESA spies were stealthed against radar, X-ray, and infrared. That served them well in tracking the Brazilians, who hadn’t mastered neutrino tech and couldn’t buy it, since none of the major powers had made their neutrino instruments for sale.

Unfortunately, the sunfishes’ sonar abilities were exquisitely honed. There was no way to hide smooth, rounded objects from them — not even objects as small as a pill.

The ESA’s answer had been to house each spy in a rough camouflage shell. Wearing these shells, which included real water or native basalt, the spies possessed the same reflective signature as ice or rock.

Advancing through the catacombs, the spies had begun to gather useful information before they came within .5 km of the sunfish, discerning activity by vibrations and sonar calls. Then the spies had approached within a few hundred meters, and their datastreams grew richer.

“The sunfish are moving in fours just like the rows of carvings,” Vonnie said. “Look how they stay together.”

“I don’t see it,” Ash said.

“Watch.”

There were twenty-three sunfish within range of the spies’ array. They scurried and pounced through thirty meters of tunnel. Some of them shoved hunks of lava into the air like baseballs or bricks. Others collected these missiles against one wall. In between, more sunfish dragged larger rocks across the floor.

Vonnie was struck again by the alien beauty of this environment. There were hot spots spread through the rock measuring a toasty -46° to -41° Celsius. Those temperatures were far below freezing, but enough heat had radiated through the spongy old lava to bake the few water molecules in the area. Then the moisture had recondensed. Film-thin drips of ice speckled the tunnel floor. In radar, the ice looked like bright coin— but as always, it was the lithe, powerful sunfish who fascinated her.

Читать дальше