Jeff Carlson

THE FROZEN SKY

Vonnie ran with her eyes shut, chasing the sound of her own boot steps. This channel in the rock was tight enough to reflect every noise back on itself, and she dodged through the space between each rattling echo.

She knew the rock was laced with crevices and pits. She knew she might catch her leg or fall with every step.

But she ran.

She crashed one shoulder against the wall. Impact spun her sideways. She hit the ground hard. Sprawled on the rock, Vonnie pushed herself up and glanced back, forgetting the danger in this simple reflex.

The bloody wet glint in her retinas was only a distraction, a useless blur of heads-up data she couldn’t read.

Worse, her helmet was transmitting sporadically, its side mount and some internals crushed beyond saving. She’d rigged a terahertz pulse that obeyed on/off commands, but her sonar and the camera spot were dead to her, flickering at random — and the spotlight was like a torch in this cold.

Vonnie clapped her glove over the gear block on her helmet, trying to muffle the beam. She wasn’t concerned about the noise of her boot steps. The entire moon groaned with seismic activity, shuddering and cracking, but heat was a give-away. Heat scarred the ice and rock. For her to look back was to increase the odds of leaving a trail.

Stupid. Stupid.

She’d never wanted to fight. Yes, the sunfish were predators. Their small bodies rippled with muscle, speed, and unrelenting aggression, but they were also beautiful in their way. They were fascinating and strange.

Were they smarter than her?

The sunfish had outmaneuvered her twice. More than anything, what Vonnie felt was regret. She could have done better. She should have waited to approach them instead of letting her pride make the decision.

In some ways Alexis Vonderach was still a girl at thirty-six, single, too smart, too good with machines and math to need many friends. She was successful. She was confident. She fit the ESA psych profile to six decimal points.

Now all that was gone. She was down to nerves and guesswork and whatever momentum she could hold onto.

She lurched forward, pawing with one hand along the soft volcanic rock. With her helmet’s ears cranked to maximum gain, each rasping touch of her boots and gloves was a roar. Larger echoes hinted at a gap above her on her left. Could she climb up? Trying to listen for the opening, she turned her head.

Her face struck a jagged outcropping in the wall. Startled, she jerked back. Then her hip banged against a different rock and she fell, safe inside her armor.

Standing was a chore she’d done hundreds of times. She did it again. She kept moving.

Vonnie didn’t think the sunfish could track the alloys of her suit, but they seemed like they were able to smell her footprints. Fresh impacts in the rock and ice left traces of dust and moisture in the air. There was no question that the sunfish were highly attuned to warmth. She’d killed nine of them in a ravine and covered her escape with an excavation charge, losing herself behind the fire and smoke… and they’d followed her easily.

What if she could use that somehow? She might be able to lead them into a trap.

Vonnie was no soldier. She had never trained for violence or even imagined it, except maybe at a few faculty budget meetings. That was an odd flicker of memory. Vonnie clung to it because it was clean and bright. She would have given anything to return to her old life, the frustrations and rewards of teaching, her classroom, and her tidy desk.

She fell once more, off-balance with her hand against her head. A heap of rubble had caught her boots and shins. She scrabbled over what appeared to be a cave-in. The noises she made were loud, clattering booms — but the echoes stretched at least ten meters above her, defining a tall chasm.

I can pin them here , she thought.

If she burned the rock and left a false trail, she could drop the rest of the broken wall on them when they passed. Then they would give up. Didn’t they have to give up? After the bloodbath in the ravine, she’d killed two more in the ice, and others had been wounded. Could the sunfish really keep soaking up casualties like that?

Vonnie could only guess at their psychology. Although she was blind, she knew of the existence of light. Although she was alone, she believed someone would find her.

She thought the history of this race was without hope. The sunfish had a phenomenal will to live, but the concept of hope required a sense of future . It required the idea of somewhere to go.

The sunfish had never imagined the stars, much less reached up to escape this black, fractured world.

This damned world.

No less than four Earth agencies had landed mecha on the surface to strip its resources. Then they’d sent a joint team in the name of science, handpicking three experts from China, America, and Europe — and Bauman and Lam had both died before First Contact, crushed in a rock swell. Would it have made any difference?

The question was too big for her. That the sunfish existed at all was a shock. Humanity had long since found Mars and Venus stillborn and barren. After more than a century and a half, the SETI radioscopes hadn’t detected any hint of another thinking race within a hundred and fifty lightyears of Earth.

Looking so far away was like a bad joke. The sunfish had been inside the solar system for millennia, a neighbor and a counterpart. It should have been the luckiest miracle. It should have been like coming home, but that had been Vonnie’s worst mistake: to think of the sunfish as similar to human beings. They were a species that seemed to lack fear or even hesitation, which might be exactly why her trap would work.

She decided to risk it. She was exhausted and hurt. If she stopped running, she would have time to attempt repairs and regain the advantage.

I hope they don’t come , she thought.

But she found a small shelf in the cliff above the rock slide, then settled in to kill more of them.

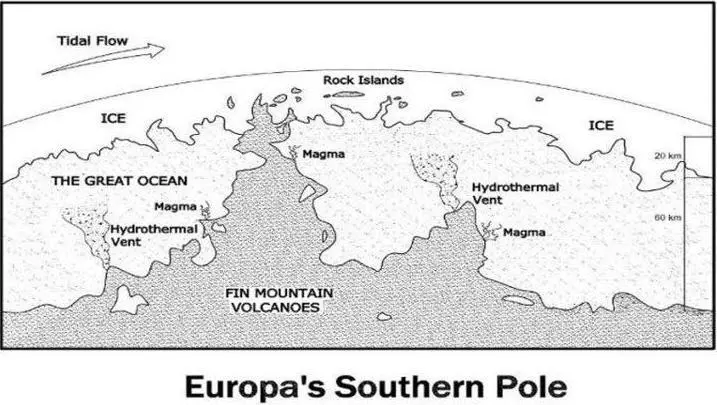

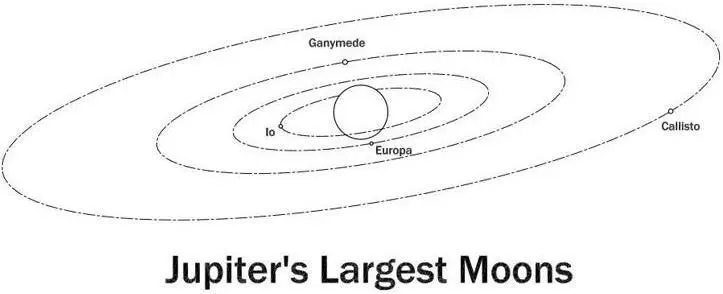

Jupiter’s sixth moon was an ocean, a deep, complete sphere too far from the sun to exist as liquid on its surface — not at temperatures of -162° Celsius. Europa was cocooned in ice. The solid crust ran as thick as twenty kilometers in some regions, which meant that for all intents and purposes, it enveloped Europa like a single continent

Human beings first walked the ice in 2094, and flybys and probes had buzzed this distant white orb since 1979. Europa was an interesting place.

For one thing, it was as large as Earth’s moon — nearly as large as Mercury — which meant it could have been a planet in its own right if it orbited the sun instead of Jupiter. It also had a unique if extremely thin oxygen atmosphere caused by the disassociation of molecules from its surface. It was water ice.

It was a natural fuel depot for fusion ships.

Before the end of the twenty-first century, the investment of fifty mecha and two dozen more in spare parts was well worth an endless supply of deuterium at the edge of human civilization. The diggers and the processing stations were fusion-powered, too. So were the tankers parked in orbit.

Читать дальше