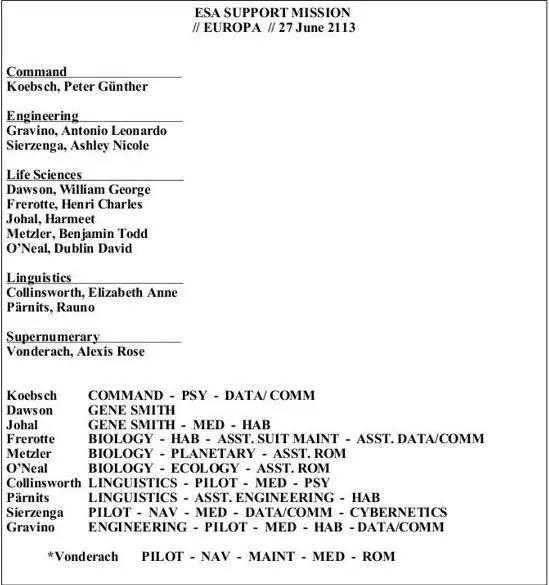

Koebsch turned beet-red as he played the satellite footage again. “We can’t stop them,” he said. “They’re not answering our signals.”

“What about emergency protocols?” Metzler asked.

“They’re blocking everything,” Koebsch said. “They knew we’d yell as soon as they breached the ice.”

“How long until we hear from Earth?”

“Nine minutes.”

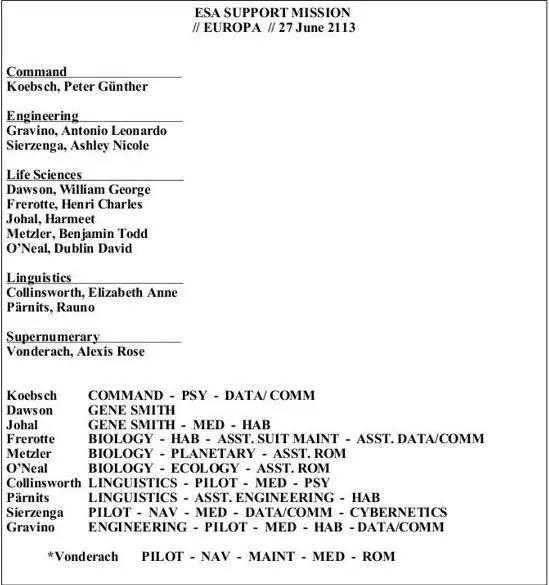

Vonnie grimaced at her showphone. She was in Lander 04 with Ash and Frerotte, but everyone had linked to their group feed, which arranged their faces in miniature around a larger holo display. The display showed fourteen mecha dropping into a rift in the ice, followed by five armored men, then six more mecha.

Five of the machines had been adapted with additional arms — short arms lined with pedicellaria. The Brazilians apparently planned to communicate with the sunfish, but it was a rushed effort. Their other mecha were crawlers, diggers, sentries, and gun platforms.

“There’s no way they’re set,” Metzler said.

Most of the ESA crew wore expressions of exasperation or disbelief. Metzler was pissed off.

In his forties, squat and ugly — so ugly he was cute, like a bulldog — Ben Metzler was a hothead and a wise-ass. In some ways, his biting opinion of people reminded her of Lam.

“The Chinese will go next,” he said. “You watch. They’ll go next and then we’ll be ordered in, too, just to show everyone who’s got the biggest dick. We’re going to contaminate this whole area.”

“I thought the Brazilians agreed to the A.N. resolutions,” Vonnie said.

Koebsch nodded. “They did.”

All sides had declared an intent to coordinate their actions and share information freely. When the time was right, the Allied Nations planned for a unified expedition. The goal was to establish a single party of translators and diplomats, but humankind was as divided as the sunfish.

The ESA wasn’t alone in running spy sats over Europa to watch their human counterparts. Some of their mecha were self-defense units, equipped mostly with electronic warfare systems. Many of their AI were committed to the same game of stealing each others’ datastreams while encrypting their own.

NASA and the ESA were old partners, often pairing with Japan, but China maintained its distance, and the Brazilians were the most recent addition to Earth’s spacefaring groups. They’d cultivated a national spirit as upstarts and underdogs.

Vonnie understood their eagerness. She identified with their need to prove themselves. She’d felt the same emotions when she’d first landed on Europa.

Why hadn’t they learned from her disaster?

As much as Vonnie wanted to contact the sunfish again, it wasn’t envy that made her want to stop the Brazilians. Until they’d run a sufficient number of probes, fully decoded the carvings and mastered the sunfish language, blundering into the ice would only make things worse.

The Brazilians’ swagger was an insult.

“Sir, they’re going in with guns ,” Vonnie said to Koebsch. “They’re either hunting specimens or looking for a fight.”

“Brazil’s in trouble,” Metzler said. “They need money to upgrade everything they’ve got — ships, suits, you name it. If they’re the first ones in and they start capturing native lifeforms, they’ll have buyers lined up out the door with cash in hand. It doesn’t matter if they kill a few sunfish. A circus is exactly what they want.”

“We can’t wait for a decision back home,” Vonnie said.

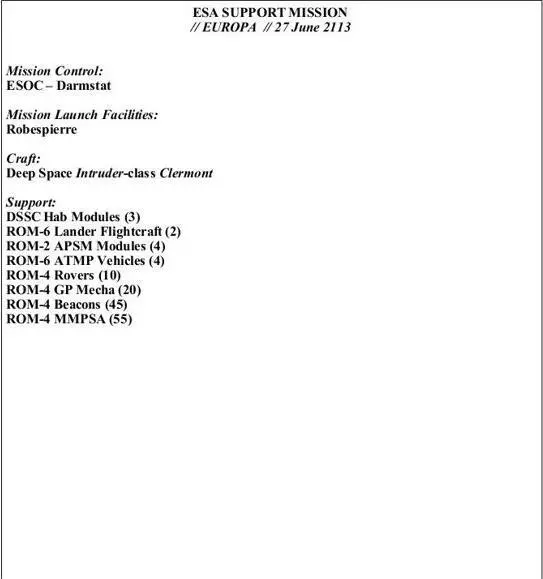

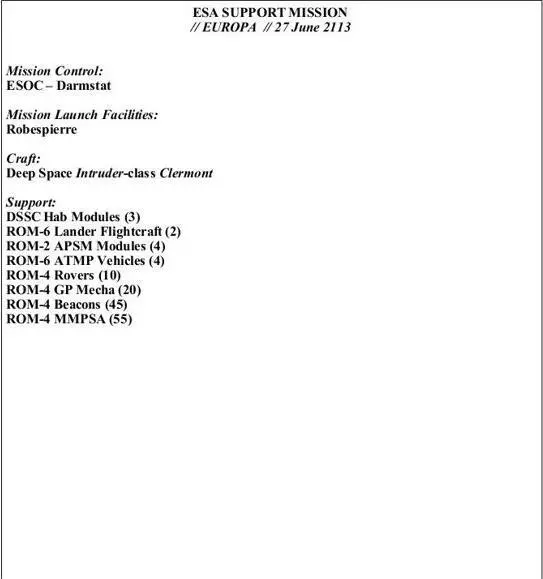

Earth was a quarter of the way around the sun from Jupiter. Each radio burst took eleven minutes to travel from the ESA camp to Berlin, the European Union capital, plus eleven minutes back again. It was a tedious way to have a conversation.

“What do you propose?” Koebsch asked.

“Let me have the display, please.” Vonnie brought up real-time surveillance of the Brazilian camp.

The place looked deserted. FNEE, the Força Nacional de Exploração do Esp , had sent less people and less mecha than any of the other three nations on Europa. Their activities had been limited, which made them easier to monitor, and yet they’d chosen a location above a more extensive system of vents than the crevices beneath the ESA camp.

“Typical,” Metzler grumbled. “We should have predicted they were up to something.”

“If five of them went in, they only left two people behind for command-and-control,” Vonnie said, highlighting one of the Brazilian hab modules where ESA satellites detected the most electronic noise. “Here.”

“You’re not talking about storming their base,” Koebsch said.

“Nothing so heavy-handed. They’ll be overwhelmed with their telemetry, and I know we’ve hacked into their net,” Vonnie said, looking at Ash and Frerotte.

Ash pursed her lips, but she nodded.

“We can shut down some of their mecha and lose the rest,” Vonnie said. “That’ll stop ’em.”

“We don’t want to hurt anybody,” Koebsch said.

“If they get stuck, they’ll send a mayday and we can walk them out. Piece of cake. That’s why we need to stop them before they go too far.”

“What do the Americans say?” Metzler asked.

“They’ll help us if they can, but we’re right on top of the problem,” Koebsch said. The ESA and Brazilian camps were only sixteen klicks apart, whereas the Americans and the Chinese were closer to the southern pole. “Ash?”

“Sir, we’re lightyears ahead of anything Brazil has in AI,” she said. “We can do it.”

Vonnie’s crew went on the offensive even as they continued to send urgent queries to Earth. Koebsch wanted the cover of waiting for instructions. Later, if necessary, he could present a convincing record that his team had been frantically, helplessly observing the Brazilians and nothing more.

Ash spearheaded the assault. She already had her elements in place. Part of her job was to ensure the ESA camp was equipped to repel cyber invasions. By necessity, some of those guardians were made to counterstrike. The most insidious weapons in her arsenal were SCPs. Sabotage and control programs were dark cousins of AI, as far evolved from their origin — computer viruses — as people were evolved from the first small hairy mammals of the Mesozoic Era two hundred million years ago.

A malevolent, replicating intelligence whose sole purpose was to corrupt healthy systems, an SCP normally included the seeds of its own destruction, a kill code, like a fuse, to prevent it from coming back at its master. Now Ash specifically tailored fifteen SCPs to pirate and transmit the Brazilians’ datastreams to the ESA camp, which would let her substitute her own signals into the Brazilian grid.

Koebsch swiftly double-checked and authorized her plan. But when she began her uploads, he questioned her.

“What were those? You sent five packets that weren’t on our list, didn’t you?” Koebsch asked, and Ash said, “I always have a few tricks up my sleeve, sir.”

Listening to the group feed, Vonnie, Metzler, and Frerotte donned their armor and walked outside, needing room to operate. They entered a maintenance shed where they would be hidden from spy sats.

Inside the shed, Vonnie studied her companions, itching to go, remembering Bauman and Lam. For the moment, no one said anything. They simply monitored their link with Ash.

She danced.

Surrounded by a virtual display, Ash tapped her gloves into a hundred blocks of data, moving like a conductor. “Slow down, slow down,” Ash said to one program as she cut her fingers through its yellow alarm bars.

Читать дальше