He ran fingers across his scalp. Sudden fear his hair might be falling out in clumps.

Sicknote stood by the barricaded door, forehead pressed to the wood panels like he was deep in prayer.

‘Told you to keep away from that door.’

Sicknote smiled and backed off.

‘You want to go outside, is that it? Want to commune with those bastards in the hall? Embrace the darkness, all that shit? Happy to oblige. Glad to see the back of you.’

Sicknote giggled and walked to the back of the plant room. He sat, rocked, and chewed his nails.

‘Stay there. Seriously. Stay put. I got too much to worry about. If you’re going to freak out for real, I’ll push you out the door. Won’t hesitate.’

Lupe sat opposite Tombes.

‘It’s all right,’ said Lupe. ‘I’ll keep my eyes on him. He won’t try anything.’

‘If he pulls any shit, I got to take steps. I don’t want to hurt the guy. I don’t want to hurt anyone. I get it: he’s nuts. It’s not his fault. But a situation like this, what else can I do?’

‘I’ll watch the guy, all right? He’s my responsibility. If there are problems, I’ll deal with it myself.’

Lupe knelt beside Ekks.

She examined his signet ring. A silver snake, eating its own tail. She tried to twist the ring from his finger. His hand slowly balled into a fist.

She studied his face. Silver hair. Wide, Slavic lips.

She leaned close and listened to breath escape his parted lips.

She clapped her hands. He didn’t flinch. His eyelids didn’t flutter. His jaw didn’t clench.

‘I doubt he is faking,’ said Cloke. ‘Nobody is that good an actor.’

‘I wouldn’t put it past this fuck. He’ll wake up when it suits him. Not before. He’ll lie there, listening to us talk, map our minds, figure out which strings to pull.’

‘You’re building this guy up into some sort of satanic manipulator.’

‘Damn right.’

Cloke threw the notebook aside. He rubbed his eyes.

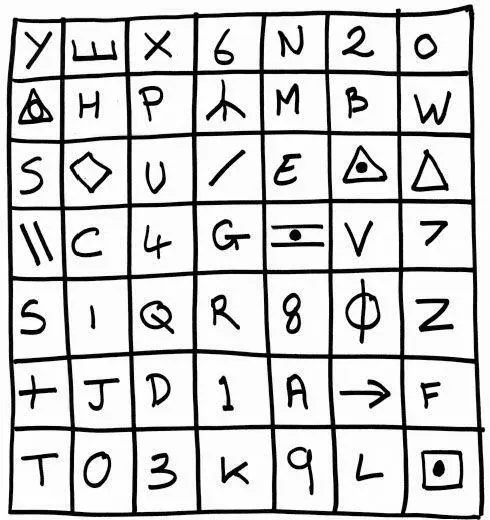

‘No luck with the code?’ asked Lupe.

‘I’m not a cipher expert. I haven’t got the right sort of mind, the right kind of logic. I’ve never won a game of chess in my life.’

‘I thought you were a scientist.’

‘A very average one. Doomed to be mediocre. Some of my college class were effortlessly accomplished. Not me. I had to study night and day. Everything came hard. That’s why I hate this damned code. A reminder of my limitations. All the times I sat over a textbook, frustrated and helpless, willing the words to make sense. We need to find a geek. Someone with an aptitude for frequency analysis.’

‘We had codes in jail,’ said Lupe. ‘We used to scribble them on the inside of cigarette packets. Little pencil marks on the foil. They’d change hands in the yard.’

‘Contract killings?’

‘No. Little stuff. Drug deals, sports bets, love tokens.’

Cloke picked up the notebook and thumbed pages.

‘I can’t help imagining what it would have been like to be down here, with Ekks, fighting the disease by his side. Dark and desperate hours.’

‘You would have died with the rest of them. Blown your brains out in that subway car.’

‘I’m a vector specialist. Competent enough in my field. I might have achieved something.’

‘You wouldn’t have achieved a damn thing,’ said Lupe. ‘Just an ugly, squalid death.’

Cloke shrugged. He turned his attention back to the notebook.

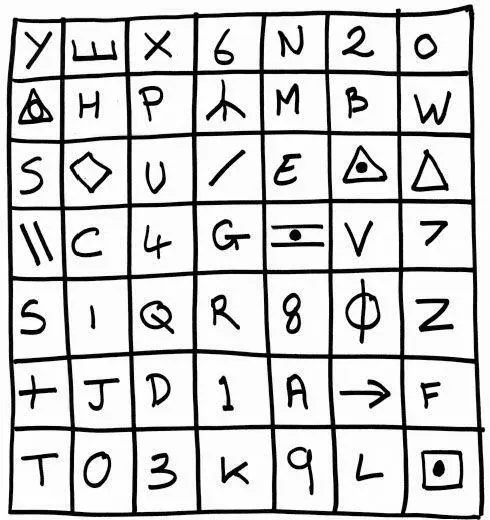

‘We need some kind of key, is that right?’ said Lupe. ‘Some kind of guide to unlock the text.’

‘Yes.’

‘He would have to write it down, yeah? It would be complicated. He couldn’t keep it in his head.’

‘Probably.’

‘What would it look like?’

‘Most likely some kind of grid or number sequence.’

‘Maybe he wrote it on his body. Have you checked him for biro marks? Little tattoos?’

‘We gave him a thorough examination. There were no marks.’

‘But you frisked him, right? You searched his pockets?’

‘It didn’t occur to me.’

Lupe leaned over Ekks and patted him down.

A dog tag hung round his neck. A tab of stamped metal with a rubber rim. She broke the ball-chain and examined the tag.

‘Feels thick.’

She peeled away the rubber rim. Two tags sandwiched together. A folded scrap of paper the size of a postage stamp between them.

‘I’ll be damned,’ murmured Cloke.

‘Is this it? The key to the cipher?’

‘Almost certainly.’

‘Then get to work.’

Tombes crouched in the corner of the room. He checked his Motorola for charge. The green power light fluttered amber. Low battery.

‘Donahue. You there?’

He held the radio close to his ear.

‘ Where else would I be? ’ Her voice little more than a whisper.

‘How you doing?’

‘ All right, I guess. Going crazy sitting in the dark. I keep hearing noises, like there’s something in the room. ’

‘What kind of sounds?’

‘ Breathing. Shuffling. Each time I check, there’s nothing. Mind playing tricks. ’

‘Feeling okay?’

‘ Nausea. Got a murderous, fuck-ass headache. ’

‘Try not to puke. You could be trapped with the stink for hours. That door still holding?’

‘ They stopped pounding the damn thing a while back. Let me check. ’

Brief pause.

‘ Yeah. Yeah, she’s good. She’s holding. ’

‘Don’t make a sound. Relentless sons of bitches. Patient, like sharks circling a boat. They’ve got our scent. Blood in the water.’

‘ Royal clusterfuck. The whole thing. ’

‘I can’t talk long. Battery is running low. I’ve got to conserve power. But you stay safe, you hear? The minute you got a problem, sound off. We’ll come running.’

‘ Okay. ’

‘Take it easy. Try to get some rest, if you can.’

David Moxon

Bellevue Dept of Neuroscience

I kept Knox company the night he died.

Ekks insisted the condemned man be extended every consideration. At the very least, he should expect the same privileges as a man on death row. He should be told his fate. He should be given a chance to make his peace with himself, his God. He should be given pen and paper, an opportunity to make a final statement.

I wasn’t present when Knox was told he was to be dissected. I heard about it later.

They took him from his chalk-outline cell. He was cuffed and led to the train, told it was part of a routine medical examination. He had endured long days without sunlight. They said they were checking for vitamin D deficiency.

He was isolated in one of the carriages. He was stripped and photographed. They shaved his head. They returned his clothes and chained him to a seat. Then they explained he was marked for death.

Harold Donner, one of the doctors from Bellevue, delivered the news. Knox was to die. He would be deliberately infected, so that Ekks and his team could study the first moments of infection. There would be no anaesthetic, no sedative. Nothing that might interfere with the validity of the results.

Knox screamed and raged. He thrashed, tried to break his cuffs, tried to break the chain that held him tethered to the seat. He begged. He pleaded. He wept.

Donner shook his head. He said he was sorry.

Knox demanded to speak to Ekks. Ekks wouldn’t talk to him. Said he was busy.

The procedure was scheduled to begin at midnight.

Knox had twelve hours to prepare himself for death.

My task?

To keep him company during the last hours of his life. Talk. Pray. Fulfil any request within my power. Above all, I was to ensure he did not escape or injure himself. When midnight came, the tie-down team would lead him to the adjacent carriage and strap him to the examination table. Then he would face the needle. A sample of the pathogen would be drawn from biological material supplied by NORAD. It would be injected into his arm.

Читать дальше