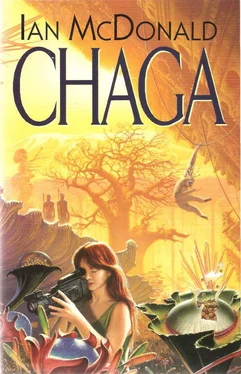

Ian McDonald - Chaga

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Chaga» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1996, ISBN: 1996, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Chaga

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0-575-06052-2

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chaga: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Chaga»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Chaga — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Chaga», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She laid her hands on the table, palms up. They were trembling.

‘Shepard, I’m sorry. I hurt you. I was crass, insensitive, selfish, treacherous, crazy; I was a hundred different sins that night, all of them deadly.’

‘You found the one wound, and you went right for it.’

‘I always do. It’s a talent of mine. It makes me good at football and terrible at relationships. I can’t help it, I probably won’t ever be able to stop it, pressing them where it hurts most. But I don’t do it deliberately. Shit, Shepard, it only works on people I love.’

‘Like now?’

‘Does this hurt?’

‘Does it ever not?’

‘How long is ever?’

‘Four years and nine months and I forget the days.’

‘Oh shit,’ Gaby McAslan said. ‘I think I’m going to have to cry now and my mascara will smudge and everyone will know. Did you really think of me all that time, Shepard? You can lie to me about this. I won’t mind, but try and make it sound convincing.’

‘Who’s lying?’ Shepard said.

‘Liar,’ Gaby whispered. ‘Do you forgive me?’

‘Long ago.’

‘Then why the fuck,’ Gaby said, in a voice so low it could hardly be heard over the rising wind, ‘did it take you four years nine months and you forget the days to tell me?’

‘A thousand stupidities. A thousand mistrusts. A thousand fears. Men are emotional cowards.’

‘You were scared? Of me?’

He said nothing. Fair comment, she thought.

‘That’s a pretty lame excuse, Shepard.’

‘What’s yours?’

‘I didn’t know if you would talk to me, let alone forgive me.’

‘Me, forgive you? But when I saw you that instant in Nairobi, in the Kenyatta tower…’

‘When I came looking for you.’

‘Exactly.’

They looked at each other over the table. The wind from out of Africa set the candle flames bickering in their glass jars and bamboo blinds billowing.

‘Do you remember in old Tom and Jerry cartoons when Spike the dog used to do something dumb?’ Gaby asked.

‘And his head would turn into a braying jackass’s?’

‘Exactly.’

‘Hee haw hee haw.’

‘I am going to cry now,’ Gaby McAslan announced.

While they made fools of themselves and each other, the voices from the telescope deck had grown louder, as had the noise from the main bar, which had gradually filled until all you could see were people’s backs pressed against the glass. Suddenly someone discovered there was an outside, and the doors slid open and the people inside poured out outside. They rushed to the rail. They seemed to be expecting an event.

‘Robert A. Heinlein’s coming down early because of the storm.’ Shepard had to raise his voice. As he spoke, miles of runway lights went on across the lagoon. Pentagrams and hexagrams of power, section by section. A hush fell over the space-watchers. ‘Is there some place quieter we could go?’ Shepard asked. ‘Someone’s bound to recognize my hair-style and want to talk to me about space.’

‘There’s my room,’ Gaby said. ‘It’s down by the pool. No one goes there, it’s not on the space side of the hotel. We don’t have to go into my room; we can just sit around the pool if you like.’

They agreed to sit on the edge of the pool with their feet in the water. Gaby listened to the stratospheric rumble of the chase planes up on the edge of the storm, hunting the in-coming shuttle with battle radar.

‘How can you contemplate this?’ she asked. She watched the circles of ripples spread out from her gently moving ankles and interfere with each other.

‘They say it’s just like a bus with wings.’

‘That pulls four gees, with five hundred tons of high explosive up its ass.’

‘If you got the chance, you’d do it too.’

Without a second thought, she said to herself.

‘Aaron’s coming down for the launch,’ Shepard said.

‘How old is he now?’ Gaby asked.

‘Almost sixteen. Terrifying amount of growing in four and a bit years. He likes me to think he’s coping well, he’s cool, he can tough it out, but he’s overcompensating. He was at the age when children use their bodies instinctively when it was taken from him, and he tries to make up for the loss with wheelchair sports: archery, basketball. He wants to train for a marathon. He pushes himself too hard – he’s just a kid still.’ Shepard emptied his glass and set it to float in the pool. The ripples carried it out into the deep water. ‘There’s an operation they want to try. It’s something they’ve developed in Ecuador from symb technology. They can splice symb neural fibres on to human nerve endings. If it works, he would walk again, run again. Be like he was. He won’t admit it, but he’s scared of it. I think he likes to be extraordinary. I think he’s afraid to go back to being an ordinary archer, an ordinary basketball player, an ordinary long distance runner. Is that a terrible thing to say about your son?’

‘Shepard, I don’t know what to say about Aaron, and Fraser. It just seems… wrong. That most of all. Wrong; an offence against nature. It’s not meant to happen like this. Parents aren’t supposed to outlive their children. Parents aren’t supposed to bury them and grieve for them and try and live the rest of their lives while thinking every day about what they should have been doing, where they should have been, what they should have achieved and experienced.’

‘It was the clothes that killed me,’ Shepard said. ‘Going through the closets, gathering all the things he used to wear; the shirts and the pants and the T-shirts and the shoes and the underwear. I couldn’t see them without seeing him in them; all these clothes he had chosen because he liked the shape or the colour or the pattern or the fashion, that he loved to wear. Laying them out and thinking, he won’t change into this T-shirt any more, or put on these short pants, or decide he feels like wearing this hat today. Things for which he has no more use. I gave them all away. I couldn’t even bear the thought of Aaron in them as hand-me-downs.

‘It’s like a fire underground, Gaby, that’s been burning down there in the dark for years, that dies down in one place and you think maybe it’s gone out, but it’s just moved somewhere else. There are coal-mine fires in Pennsylvania that have burned down under the earth for whole lifetimes.’

‘I envy you that fire,’ Gaby said. ‘Really. Truly. My ovaries kick me every time you mention their names, Shepard. I goggle at babies in buggies. I linger in children’s clothing stores; the sad woman by the 0 to 6 months who’s too scared to pick up and feel that cute little red dress. My biological clock is saying “Hurry up now, it’s time.” Looming thirtysomethinghood. I always envied you your kids, did you know that, Shepard? I used to think I envied their claim over you; now I know it was that they were kids that I envied. I’m tired of having nothing outside of me to care about.’

The wind was blowing hard now, flapping their clothes, ruffling the surface of the pool into wavelets that swamped the whiskey glass and sent it to the bottom of the deep end.

‘Gaby,’ Shepard said, ‘come and swim with me.’ His voice was thick with want. He stood up, took off his Indian-style suit that did not really flatter him. His body was as hairless as his head. ‘It’s how we train for freefall. Swim with me, Gaby. I love to see women in water. Women swimming.’

Dizzy with anticipation, Gaby stripped down to her panties and followed Shepard into the pool. He was waiting for her in the deep water where the whiskey glass had sunk. She swam towards him, pleasuring herself in the slide of water past her body. So wet women do it, Shepard? She trod water beside him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Chaga»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Chaga» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Chaga» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.