He stood there staring. For a moment the disintegration of the figure filled him with a sense of grotesque horror and dismay. For a moment it seemed beyond the sanity of things. Then, as he realised the deception his senses had contrived, he sat down again, put his elbows on the table and buried his face in his hands.

About ten he came and told me. He told me in a clear hard voice, without a touch of emotion, recording a remarkable fact. “As I told you the other thing, it is only right that I should tell you this,” he said.

Then he sat silently for a space. “She will come no more,” he said at last. “She will come no more.”

And suddenly he rose, and without a greeting, passed out into the night.

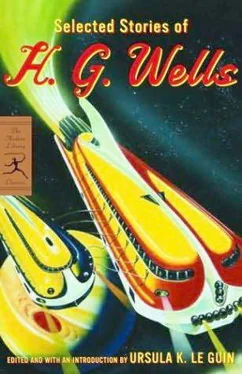

To my mind, fable differs from fantasy chiefly by having a didactic aim. Aunt Fantasy tells her tales for their own sake; Uncle Aesop wants us to get the point. (In science fiction, there is a similar difference between stories of other times or planets and the didactic utopia/dystopia.) Fable is often funny or satirical, and uses a pretty broad brush.

These four stories all make their point boldly. “A Vision of Judgment” is an early story, brash and brilliant. H. G. Wells was not what anyone would call a God-fearing man. I think he felt God had a right to ask for respect, but not for fear.

The next two tales, “The Story of the Last Trump” and “The Wild Asses of the Devil” appeared as chapters of a 1915 novel, Boon. Wells himself put “Last Trump” into a collection, The Door in the Wall; and let us again be grateful to John Hammond for including “Wild Asses” in The Complete Short Stories of H. G. Wells, for both pieces stand on their own as inventive and entertaining tales.

“Answer to Prayer” was written much later than all but one of the stories in this book, in 1937, when Wells was seventy-one. It is very short and not sweet.

BRU-A-A-A.

I listened, not understanding.

Wa-ra-ra-ra.

“Good Lord!” said I, still only half-awake. “What an infernal shindy!”

Ra-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra. Ta-ra-rra-ra.

“It’s enough,” said I, “to wake—” and stopped short. Where was I?

Ta-rra-rara—louder and louder.

“It’s either some new invention—”

Toora-toora-toora! Deafening!

“No,” said I, speaking loud in order to hear myself. “That’s the Last Trump.”

Tooo-rraa!

The last note jerked me out of my grave like a hooked minnow.

I saw my monument (rather a mean little affair, and I wished I knew who’d done it), and the old elm tree and the sea view vanished like a puff of steam, and then all about me—a multitude no man could number, nations, tongues, kingdoms, people—children of all the ages, in an amphitheatrical space as vast as the sky. And over against us, seated on a throne of dazzling white cloud, the Lord God and all the host of his angels. I recognised Azreal by his darkness and Michael by his sword, and the great angel who had blown the trumpet stood with the trumpet still half-raised.

“Prompt,” said the little man beside me. “Very prompt. Do you see the angel with the book?”

He was ducking and craning his head about to see over and under and between the souls that crowded round us. “Everybody’s here,” he said. “Everybody. And now we shall know—

“There’s Darwin,” he said, going off at a tangent. “ He’ll catch it! And there—you see?—that tall, important-looking man trying to catch the eye of the Lord God, that’s the Duke. But there’s a lot of people one doesn’t know.

“Oh! there’s Priggles, the publisher. I have always wondered about printers’ overs. Priggles was a clever man… But we shall know now— even about him.

“I shall hear all that. I shall get most of the fun before… My letter’s S.”

He drew the air in between his teeth.

“Historical characters, too. See? That’s Henry the Eighth. There’ll be a good bit of evidence. Oh, damn! He’s Tudor.”

He lowered his voice. “Notice this chap, just in front of us, all covered with hair. Paleolithic, you know. And there again—”

But I did not heed him, because I was looking at the Lord God.

“Is this all?” asked the Lord God.

The angel at the book—it was one of countless volumes, like the British Museum Reading-room Catalogue, glanced at us and seemed to count us in the instant.

“That’s all,” he said, and added: “It was, O God, a very little planet.”

The eyes of God surveyed us.

“Let us begin,” said the Lord God.

The angel opened the book and read a name. It was a name full of A’s, and the echoes of it came back out of the uttermost parts of space. I did not catch it clearly, because the little man beside me said, in a sharp jerk, “ What’s that?” It sounded like “Ahab” to me; but it could not have been the Ahab of Scripture.

Instantly a small black figure was lifted up to a puffy cloud at the very feet of God. It was a stiff little figure, dressed in rich outlandish robes and crowned, and it folded its arms and scowled.

“Well?” said God, looking down at him.

We were privileged to hear the reply, and indeed the acoustic properties of the place were marvellous.

“I plead guilty,” said the little figure.

“Tell them what you have done,” said the Lord God.

“I was a king,” said the little figure, “a great king, and I was lustful and proud and cruel. I made wars, I devastated countries, I built palaces, and the mortar was the blood of men. Hear, O God, the witnesses against me, calling to you for vengeance. Hundreds and thousands of witnesses.” He waved his hands towards us. “And worse! I took a prophet—one of your prophets—”

“One of my prophets,” said the Lord God.

“And because he would not bow to me, I tortured him for four days and nights, and in the end he died. I did more, O God, I blasphemed. I robbed you of your honours—”

“Robbed me of my honours,” said the Lord God.

“I caused myself to be worshipped in your stead. No evil was there but I practised it; no cruelty wherewith I did not stain my soul. And at last you smote me, O God!”

God raised his eyebrows slightly.

“And I was slain in battle. And so I stand before you, meet for your nethermost Hell! Out of your greatness daring no lies, daring no pleas, but telling the truth of my iniquities before all mankind.”

He ceased. His face I saw distinctly, and it seemed to me white and terrible and proud and strangely noble. I thought of Milton’s Satan.

“Most of that is from the Obelisk,” said the Recording Angel, finger on page.

“It is,” said the Tyrannous Man, with a faint touch of surprise.

Then suddenly God bent forward and took this man in his hand, and held him up on his palm as if to see him better. He was just a little dark stroke in the middle of God’s palm.

“ Did he do all this?” said the Lord God.

The Recording Angel flattened his book with his hand.

“In a way,” said the Recording Angel, carelessly.

Now when I looked again at the little man his face had changed in a very curious manner. He was looking at the Recording Angel with a strange apprehension in his eyes, and one hand fluttered to his mouth. Just the movement of a muscle or so, and all that dignity of defiance was gone.

“Read,” said the Lord God.

And the angel read, explaining very carefully and fully all the wickedness of the Wicked Man. It was quite an intellectual treat.—A little “daring” in places, I thought, but of course Heaven has its privileges…

Читать дальше