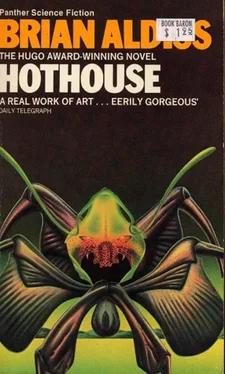

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'So we learned that the Lands of Perpetual Twilight, for all their apparent emptiness, have offered shelter to many creatures. Always these creatures are going the same way.

'Always they come from the bright green lands over which the sun burns. Always they are heading either for extinction or for the lands of Night Eternal – and often the two mean the same thing.

'Each wave of creatures may stay here for several generations. But always it is forced farther and farther from the sun by its successors.

'Once there flourished here a race we know as the Pack People because they hunted in packs – as the sharp-furs will do in a crisis, but with far more organization. Like the sharp-furs, the Pack People were sharp of teeth and brought forth living young, but they moved always on all-fours.

'The Pack People were mammal but non-human. Such distinctions are vague to me, for Distinguishing is not one of my subjects, but your kind once knew the Pack People as wolves, I believe.

'After the Pack People came a hardy race of some kind of human, who brought with them four-footed creatures which supplied them with food and clothing, and with which they mated.'

'Can that be possible?' Gren asked.

'I only repeat to you the old legends. Possibilities are no concern of mine. Anyhow, these people were called Shipperds. They drove out the Packers and were in turn superseded by the Howlers, the species that legend says grew from the matings between the Shipperds and their creatures. Some Howlers still survive, but they were mainly killed in the next invasion, when the Heavers appeared. The Heavers were nomadic -I've run into a few of them, but they're savage brutes. Next came another off-shoot of humanity, the Arablers, a race with some small gift for cultivating crops, and no other abilities.

'The Arablers were quickly overrun by the sharp-furs, or Bamboons, to give them their proper name.

'The sharp-furs have lived in this region in greater or lesser strength for ages. Indeed, the myths say they wrested the gift of cooking from the Arablers, the gift of sledge transport from the Heavers, the gift of fire from the Packers, and the gift of speech from the Shipperds, and so on. How true that is, I don't know. The fact remains that the sharp-furs have overrun the land.

'They are capricious and untrustworthy. Sometimes they will obey me, sometimes not. Fortunately they are afraid of the powers of my species.

'I should not be surprised if you tree-dwelling humans – Sandwichers, did I hear the belly men call you? – aren't the forerunners of the next wave of invaders. Not that you'd be aware of it if you were...'

Much of this monologue was lost on Gren and Yattmur, particularly as they had to concentrate on their progress across a stony valley.

'And who are these people you have as slaves here?' Gren asked, indicating the carrying man and the women.

'As I should have thought you might have gathered, these are specimens of Arablers. They would all have died out but for our protection.

'The Arablers, you see, are devolving. I may possibly explain what I mean by that some other time. They have devolved furthest. They will turn into vegetables if sterility does not obliterate the race first. Long ago they lost even the art of speech. Although I say lost, this was in fact an achievement, for they could only survive at all by renouncing everything that stood between them and vegetative level.

This sort of change is not surprising under present conditions on this world, but with it went a more unusual transformation. The Arablers lost the notion of passing time; after all, there is no longer anything to remind us daily or seasonally of time: so the Arablers in their decline forgot it entirely. For them there was simply the individual life span. It was – it is, the only time span they are capable of recognizing: the period-of-being.

'So they have developed a co-extensive life, living where they need along that span.'

Yattmur and Gren looked blankly through the gloom at each other.

'Do you mean these women can move forward or backward in time?' Yattmur asked.

'That wasn't what I said: nor was it how the Arablers would express it. Their minds are not like mine nor even like yours, but when for instance we came to the bridge guarded by the sharp-fur with the torch, I got one of the women to move along her period-of-being to see if we crossed the bridge uneventfully.

'She returned and reported that we did. We advanced and she was proved right, as usual.

'Of course they only operate when danger threatens; this spanning process is primarily a form of defence. For instance, when Yattmur brought us food the first time, I made the spanning woman span ahead to see if it poisoned us. When she returned and reported us still alive, then I knew it was safe to eat.

'And similarly when I first saw you with the sharp-furs and – what do you call them? – the belly-tummy men, I sent the spanning woman to see if you would attack us. So you see even a miserable race like the Arablers have their uses!'

They were forging slowly ahead through foothills, travelling through a deep green gloom nourished by sunshine reflected from cloud banks overhead. Ever and again they caught a glimpse of moving lights over on their left flank; the sharp-furs were still following them, and had added more torches to their original one.

As the sodal talked, Gren stared with new curiosity at the two Arabler women leading their party.

Because they were naked, he could see how little their sexual characteristics were developed. Their hair was scanty on the head, non-existent on the mons veneris. Their hips were narrow, their breasts flat and pendulous, although, as far as one could judge their age, they did not seem old.

They walked with neither enthusiasm nor hesitation, never glancing back. One of the women carried on her head the gourd that held the morel.

Through Gren ran a sort of awe to feel how different must be the understandings of these women from his own; what could their lives be like, how would their thoughts flow, when their period-of-being was not a consecutive but a concurrent vista?

He asked Sodal Ye, 'Are these Arablers happy?'

The catchy-carry-kind laughed throatily.

'I've never thought to ask them such a question.'

'Ask them now.'

With an impatient flip of his tail, the sodal said, 'All you human and similar kinds are cursed with inquisitiveness. It's a horrible trait that will get you nowhere. Why should I speak to them just to gratify your curiosity?

'Besides, it needs absolute nullity of intelligence to be able to span; to fail to distinguish between past and present and future needs a great concentration of ignorance. The Arablers have no language at all; once introduce them to the idea of verbalization and their wings are clipped. If they talk, they can't span. If they span, they can't talk.

"That's why it is always necessary for me to have two women with me – women preferably, because they are even more ignorant than the men. One woman has been taught a few words so that I can give her commands; she communicates them by gesture to her friend, who can thus be made to span when danger threatens. It is all rather roughly devised, but it has saved me much trouble on my journeys.'

'What about the poor fellow who carries you?' Yattmur asked.

From Sodal Ye came a vibrating growl of contempt.

'A lazy brute, nothing but a lazy brute! I've ridden him since he was a lad and he's very near worn out already. Hup, you idle monster! Get along there, or we'll never be home.'

Much more the sodal told them. To some of it Gren and Yattmur responded with concealed anger. To some of it they paid no heed. The sodal orated unceasingly, until his voice became merely another factor in the lightning-cluttered gloom.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.