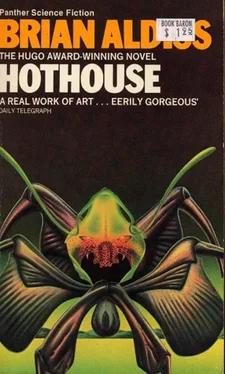

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Come on!' she called encouragingly. 'You fellows come with us and we'll look after you.'

'They've been trouble enough to us,' Gren said. Stooping, he collected a handful of stones and flung them.

One tummy-belly was hit in the groin, one on the shoulder, before they broke and fled back into the cave, crying aloud that nobody loved them.

'You are too cruel, Gren. We should not leave them at the mercy of the sharp-furs.'

'I tell you I've had enough of those creatures. We are better on our own.' He patted her shoulder, but she remained unconvinced.

As they moved down Big Slope, the cries of the tummy-bellies died behind them. Nor would their voices ever reach Gren and Yattmur again.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

THEY descended the ragged flank of Big Slope and the shadows of the valley rose up to meet them. A moment came when they waded in dark up to their ankles; then it rose rapidly, swallowing them, as the sun was hidden by a range of hills ahead.

The pool of darkness in which they now moved, and in which they were to travel for some while, was not total. Though at present no cloud banks overhead reflected the light of the sun, the frequent lightning traced out their path for them.

Where the rivulets of Big Slope gathered into a fair-sized stream, the way became precipitous, for the water had carved a gully for itself, and they were forced to follow along its higher bank, going in single file along a steep cliff edge. The need for care slowed them. They descended laboriously round boulders, many of them clearly dislodged by the recent earth tremors. Apart from the sound of their footsteps, the only noise to compete with the stream was the regular groaning of the carrying man.

Soon a roaring somewhere ahead told them of a waterfall. Peering into the gloom, they saw a light. It was burning on what, as far as they could discern, was the lip of the cliff. The procession halted, bunching protectively together.

'What is it?' Gren asked. 'What sort of creature lives in this miserable pit?'

Nobody answered.

Sodal Ye grunted something to the talking woman, who in turn grunted at her mute companion. The mute companion began to vanish where she stood, rigid in an attitude of attention.

Yattmur clasped Gren's arm. It was the first time he had seen this disappearing act. Shadows all about them made it the more uncanny, as a ragged incline showed through her body. For a while her tattoo lines hung seemingly unsupported in the gloom. He strained his eyes to see. She had gone, was as intangible as the resonance of falling water.

They held their tableau until she returned.

Wordlessly the woman made a few gestures, which the other woman interpreted into grunts for the sodal's benefit. Slapping his tail round his porter's calves to get him moving again, the sodal said, 'It's safe. One or two of the sharp-furs are there, possibly guarding a bridge, but they'll go away.'

'How do you know?' Gren demanded.

'It will help if we make a noise,' said Sodal Ye, ignoring Gren's question. Immediately he let out a deep baying call that startled Yattmur and Gren out of their wits and set the baby wailing.

As they moved forward, the light flickered and went over the lip of the cliff. Arriving at the point where it had been, they could look down a steep slope. Lightning revealed six or eight of the snouted creatures bouncing and leaping into the ravine, one of them carrying a crude torch. Ever and again they looked back over their shoulders, barking invective.

'How did you know they'd go away?' Gren asked.

'Don't talk so much. We must go carefully here.'

They had come to a sort of bridge: one cliff of the gully had fallen forward in a solid slab, causing the stream to tunnel beneath it before splashing down into the nearby ravine; the slab rested against the opposite cliff, forming an arch over the flood. Because the way looked so broken and uncertain, its hazards increased in the twilight, the party moved hesitantly. Yet they had hardly stepped on to the crumbling bridge when a host of tiny beings clattered up startlingly from beneath their feet.

The air flaked into black flying fragments.

Savage with startlement, Gren struck out, punching at small bodies as they rocketed past him. Then they had lifted. Looking up, he saw a host of creatures circling and dipping over their heads.

'Only bats,' said Sodal Ye casually. 'Move on. You human creatures have a poor turn of speed.'

They moved. Again the lightning flashed, bleaching the world into a momentary still life. In the ruts at their feet, and just below them, and over the bridge side, reaching down to the tumbling waters, glistened such spiders' webs as Gren and Yattmur had never seen before, like a multitude of beards growing into the river.

She exclaimed about them, and the sodal said loftily, 'You don't realize the facts behind the curious sight you see here. How could you, being mere landlivers? – Intelligence has always come from the seas. We sodals are the only keepers of the world's wisdom.'

'You certainly didn't concentrate on modesty,' Gren said, as he helped Yattmur on to the farther side.

'The bats and the spiders were inhabitants of the old cool world, many eons ago,' said the sodal, 'but the growth of the vegetable kingdom forced them to adopt new ways of life or perish. So they gradually moved away from the fiercest competition into the dark, to which the bats at least were predisposed. And in so doing the two species formed an alliance.'

He went on discoursing with the smoothness of a preacher even while his porter, aided by the tattooed women, heaved and strained and groaned to pull him up a broken bank on to firm ground. The voice poured forth with assurance, as thick and velvety as the night itself.

'The spider needs warmth for her eggs to hatch, or more warmth than she can get here. So she lays them, sews them into a bag, and the bat obligingly carries them up to Big Slope or one of these other peaks that catch the sun. When they hatch, he obligingly brings the progeny back again. Nor does he work for nothing.

'The grown spiders weave two webs, one an ordinary one, the other half in and half out of the water, so that the lower part of it forms a net below the surface. They catch fish or small living things in it and then hoist them out into the air for the bats to eat. Any number of similar strange things go on here of which you land-dwellers would have no knowledge.'

They were now travelling along an escarpment that sloped down into a plain. Emerging as they were from under the bulk of a mountain, they slowly gained a better view of the terrain round about. From the tissue of shadows soared an occasional crimson cone of a hill lofty enough to bathe its cap in sunlight. Gathering cloud threw a glow over the land that changed minute by minute. Landmarks were thus by turns revealed and hidden as though by drifting curtains. Gradually the clouds blanketed the sun itself, so that they had to travel with additional caution through a thicker obscurity.

Over to the left appeared a wavering light. If it was the one they had seen by the ravine, then the sharp-furs kept pace with them. The sight reminded Gren of his earlier question.

'How does this woman of yours vanish, Sodal?' he asked.

'We have a long way yet to go before reaching the Bountiful Basin,' declared the sodal. 'Perhaps it will therefore amuse me to answer your question fully, since you seem a mite more interesting than most of your kind.

'The history of the lands through which we travel can never be pieced together, for the beings that lived here have vanished leaving no records but their unwanted bones. Yet there are legends. My race of the catchy-carry-kind are great travellers; we have travelled widely and through many generations; and we have collected these legends.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.