“You and me both, Ma’am,” Tobias agreed in turn, giving her a look which held a hint of approval. “Never did seem fair to just throw ‘em away when they got too old,” he continued. “Of course, the older models-before the XXIVs and XXVs-probably had too many inhibitory features to make upgrading their AIs into new marks practical. They weren’t really designed to be upgraded in the first place.”

“I know.” Maneka started to say something more, then changed her mind as the two of them stepped into the shadow of the looming Bolo. She half-expected Tobias to immediately introduce her to the huge combat machine, but the sergeant waited patiently for her to absorb its full impact, first.

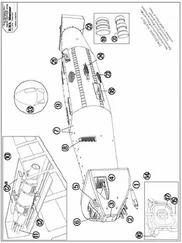

Unit 28/G-862-BNJ was a 15,000-ton Mark XXVIII, Model G, Bolo, one of the old Triumphants. His hull measured eighty-seven meters from his much-decorated prow to his aftermost antipersonnel clusters and point defense cannon. His bogey wheels were almost six meters in diameter, his tracks were eight meters wide, and the top of his center-mounted main battery turret rose twenty-seven meters above the ground, yet he was so broad and long that he still seemed low-slung, almost sleek. His indirect fire system was divided, with his four 30-centimeter rapid-fire breech-loading mortars mounted forward of his turret, and the twenty-four cells of his vertical-launch missile system mounted behind it. The secondary weapons of his infinite repeaters bristled in a lozenge pattern around the central turret, eight 10-centimeter ion-bolt rifles in four twin turrets on either flank, with a pair of single turrets mounted on the centerline fore and aft of the main turret. The broadside turrets were echeloned to allow at least five infinite repeaters to engage on any target bearing, and while the ion-bolt armament was far less powerful than the small-bore Hellbores mounted as secondary weapons aboard current model Bolos, Maneka knew the 10-centimeter version mounted in the Mark XXVIII would penetrate better than a quarter-meter of duralloy at close ranges. And if the 110-centimeter Hellbore of BNJ’s main armament was much lighter than the current-generation 200-centimeter weapons, it could still pump out 2.75 megatons/second.

BNJ’s glacis glittered with the welded-on battle honors of well over a century of active service. Maneka recognized perhaps half of the campaign ribbons, including awards for several of the Xalontese and Deng War campaigns. She felt embarrassed at not recognizing the others and made a mental note to look them up as soon as possible. But if she failed to recognize some of those, the awards for valor were another matter. She ran her eyes down the long, glittering row of platinum and rhodium stars and tried not to show her reaction to the discovery that BNJ had received no less than three Galactic Clusters. There were probably at least some equally or even more highly decorated Bolos still in service, but there could not have been many.

And yet, for all the Mark XXVIII’s undoubted firepower and all BNJ’s proven lethality and courage, Colonel Tchaikovsky and Sergeant Tobias were right. BNJ and his brothers and sisters were no longer fit for combat against first-line enemy opposition.

At the Academy, Maneka had studied everything she could get her hands on about the Melconian Empire’s ground combat systems, and she knew the human advantage in psychotronics and artificial intelligence generally gave even older Bolos like BNJ an enormous edge in any one-on-one confrontation with the Puppies’ manned armored units. The Melconian heavy combat mechs-the Surturs, as the Concordiat had code-named them-had heavy AI support, but the AIs in question were far less capable and required command inputs at almost every stage. They were roughly equivalent to an old Mark XX, or possibly only to a Mark XIX, albeit with far more powerful weapons than those ancient Bolos had mounted: fast, lethal, and capable as long as they operated within preplanned “canned” battle plans, but much slower than any current-inventory Bolo when faced with tactical situations outside their preprogrammed plans.

But if their cybernetics were vastly inferior to the Concordiat’s psychotronic-based systems, they were also less massive, and the Melconians had accepted the use of antimatter-reactors rather than the bulkier cold-fusion plants humanity employed. The result was an 18,000-ton fighting machine with two echeloned main turrets, each mounting the Melconian equivalent of three 81-centimeter Hellbores. The turret arrangement meant that each turret masked the other’s fire over an arc of about twenty-five degrees, but that still meant all six Hellbores could be brought to bear on a single target over a three hundred and ten-degree field of fire. That much main battery armament meant that the Surtur’s secondary armament was inevitably much lighter than current-generation Bolos mounted, although it was heavier than that of an older model, like BNJ, and the Surtur came in two distinct variants. One “standard” model, and a “support” model which suppressed the secondary armament almost entirely in favor of an indirect fire capability at least twenty-five percent heavier than BNJ’s.

The Surtur’s stablemate, the medium mech the Concordiat had code-named Garm, weighed in at barely nine thousand tons and was hopelessly outclassed against any Bolo. But the Melconians operated their armored forces in tactical units, called “fists,” each of which combined one Surtur with two of the Garms. With the lighter Garms to probe ahead and provide flanking units under the command Surtur’s tight tactical control, a Melconian “fist” was probably the most dangerous foe a unit of the Dinochrome Brigade had faced in centuries.

And there were a lot of fists out there. Which was one reason the Academy was now graduating two classes a year, instead of one.

As those thoughts flashed through her, BNJ’s forward main optical head unhoused itself and swivelled around to face her. She felt particularly buglike as the mammoth Bolo regarded her with every appearance of watching thoughtfulness, and her mouth wanted to twitch into a smile at the thought of how ridiculous she must look standing in front of him, with the top of her head reaching barely a quarter of the way up one of his bogey wheels.

“Benjy,” Sergeant Schumer said after a moment, “this is Lieutenant Trevor.”

The introduction, Maneka knew, was purely a formality. BNJ-it was considered the height of bad manners to refer to any Bolo by its cognomen until after one had been formally introduced to it-had undoubtedly scanned her implant IFF the instant she crossed his defensive zone perimeter. But over the centuries the Brigade had evolved an ironbound tradition of proper protocol and courtesy.

“I am pleased to meet you, Lieutenant,” a resonant baritone said pleasantly over the Bolo’s external speakers.

“Thank you,” she replied.

“The Lieutenant’s being assigned as your new Commander, Benjy,” Schumer said. “Command authentication: ‘When the bluebirds sing in the spring.’”

“Authentication accepted.” A red light blinked on the optical head, and then the baritone voice spoke again, this time directly to Maneka. “Unit Two-Eight-Golf-Eight-Six-Two-Baker-November-Juliette of the Line awaiting orders, Commander,” it said.

“Thank you, Benjy.” Maneka fought, almost successfully, to keep the tremors out of her voice as for the first time one of the stupendous, awe-inspiring war machines she had trained for almost eight Standard Years to command acknowledged her authority. She had never expected this moment to come so early in her career, even with the war’s intensity growing steadily to fresh heights of violence, and she inhaled deeply as she savored it.

“You’ll have to give Benjy his head a bit more, Lieutenant,” Major Angela Fredericks said over Maneka’s mastoid transceiver from her command couch aboard Unit 28/D-302-PGY. Her voice wasn’t precisely unpleasant, but it most definitely was pointed. “Don’t second-guess him. You don’t have the experience for that yet.”

Читать дальше