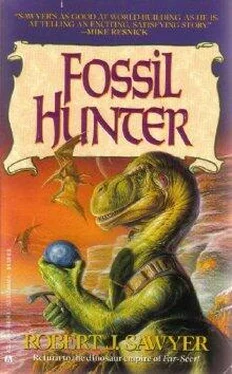

Robert Sawyer - Fossil Hunter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Sawyer - Fossil Hunter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Ace Science Fiction, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Fossil Hunter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ace Science Fiction

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- ISBN:0-765-30793-4

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fossil Hunter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Fossil Hunter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

trilogy depicts an Earth-like world on a moon which orbits a gas giant, inhabited by a species of highly evolved, sentient Tyrannosaurs called Quintaglios, among various other creatures from the late cretaceous period, imported to this moon by aliens 65 million years prior to the story.

Fossil Hunter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Fossil Hunter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Although a hornface could easily accommodate four large riders, Galpook’s primary group consisted of ten animals each with but one rider. They headed off in single file to the west. The sun, a fierce white point, was about halfway up the purple sky. Wisps of white cloud were visible, as were three pale daytime moons, two crescent and one almost full.

Off in the distance, Galpook thought she saw a giant wingfinger, rising and falling in the sky. Such giants mostly fed on fish and aquatic lizards, but there were a few who would simply follow a blackdeath for days, waiting for it to make a kill, knowing that even the most famished of the dark horrors would leave huge amounts of meat on a carcass. Perhaps this one, far away, was indeed following the blackdeath Galpook and her team were now pursuing.

Like shovelmouths, lumbering hornfaces were also known for their pungent flatulence. Galpook, in the lead, was taking the full brunt of the excesses of ten beasts, for the steady daytime wind was blowing from behind. Conversely, her own pheromones—Galpook had been named hunt leader because she was one of those rare females who were in perpetual heat—were being blown ahead of the pack, instead of back on the hunters. It was too bad: exposure to such smells honed the senses.

The Ch’mar peaks made a ragged line ahead, like torn paper. Galpook thought back to how they had looked before the great eruption of sixteen kilodays ago. It still startled her sometimes to see them as they now appeared, the cone of the leftmost caved in on one side, one of the mountains in the middle now half again the height it used to be, a third burst open like a puckered sore.

Galpook didn’t really like riding. The constant up-and-down heaving of the hornface’s flanks was uncomfortable. But she needed to save her strength for what was ahead. She looked over her shoulder. Behind her, nine more hornfaces lumbered along, each with a Quintaglio rider. Four of the brutes hauled wagons. And behind them, mostly on foot, the secondary team.

The sun was rising with not-quite-visible speed. Insects buzzed. The hunting party continued on. The Ch’mar peaks grew closer, closer still, until at last they loomed before the caravan, black and gray bulks, their stony perfection marred by some scraggly vegetation here and there. At intervals, little waterfalls trickled down the tortuous rock faces, black sands accumulating around the bases of the mountains. The pounding of the hornfaces’ round feet kicked up gray clouds of rock dust. The great wingfinger Galpook had spotted earlier continued to glide high above in vast, leisurely circles. Occasionally it cut loose its call, a high-pitched keening that also seemed to waft on the hot currents of air.

Night fell. They continued on. As they passed the foothills, early the next day, the members of the secondary team stopped, waiting until they were needed, but Galpook’s primary team forged ahead. At last they came to the ruins of the Temple of Lubal, one of the five original hunters.

Much damage had been done to the temple grounds in the last great series of landquakes, sixteen kilodays ago. Dybo’s mother, Lends, had been contemplating ordering excavations here shortly before her death, but the latest lava flows had plugged up the ruins so severely that no practical digging was possible and Dybo had abandoned the idea. There was a smooth gray plain of stone, looking like a calm lake on a leaden morn, stretching out before them. The tops of buildings poked through, like half-sunk ships, but they were strangely twisted, as if in the heat of the eruption they had partially melted, flowing into malformed shapes. Of the Spires of the Original Five, representing the upward-stretched fingers of the Hand of God from which Lubal, Katoon, Belbar, Mekt, and Hoog had sprung, only two were still intact, poking like lances out of the basalt plain. The other three had tumbled, breaking into the tapering stone disks from which they’d been assembled, like chains of vertebrae half-caught in the volcanic rock.

Everything was still, frozen in congealed lava, a tableau, the aftermath of the volcanic fury that once had come close to destroying the Capital. From here, three days ago, a blackdeath had been sighted. But where was the beast now? Where?

Galpook looked up. The center point of the wingfinger’s circular gliding was almost directly overhead. If it had been following the blackdeath, then that creature must be nearby. But perhaps the giant flyer had given up on the blackdeath, and had decided instead that the hunting party itself represented the most likely source of its next meal. Galpook wondered idly what defense she’d employ against the beast should it swoop down upon her, its great hairy wings flapping, its long, pointed prow snapping opened and closed.

Galpook swung slowly off the shoulders of her bossnosed mount and lowered herself to the ground. Her toeclaws ticked against the gray basalt, but the underside of her tail, callused though it was, slid smoothly over the flat, dry rock. She walked back to the first of the hornfaces that was pulling a wagon and motioned for her assistant, Foss, who was riding that creature, to help her. He slid down to the ground and came over to join Galpook. Together, they clambered into the wagon and uncovered the device Gan-Pradak, the chief palace engineer, had built for them. At its heart was the skull of a tube-crested shovelmouth, glaring white in the sun, which was now well past the zenith. The skull, including the giant backward-pointing crest, was longer than Galpook’s arm-span. The engineer had plugged the pre-orbital fenestrae and eye sockets with clay and had attached a great bellows supported by a wooden brace to the back of the skull.

Galpook and Foss grabbed the upper arm of the bellows and pulled down with all their weight. The bellows pumped air into the crest and a great thundering noise emanated from the skull’s nostril holes. Galpook and Foss pumped the bellows again and again. The other hunters covered their ears and the hornfaces made low sounds of pain. After ten repetitions, they were tired and stopped, but for several moments the ersatz shovelmouth call continued to echo off the mountainsides. Galpook lifted her tail to dissipate heat; Foss’s dewlap waggled in the breeze.

The ruse was working on the wingfinger, at least. It had dropped to a much lower altitude, evidently assuming the repetitious bellowing signified a shovelmouth in great distress.

Having recuperated, Foss and Galpook operated the bellows again, pumping air through the shoveler’s skull, forcing out the great cries the skull’s original owner had once made in life. Again and again and—

There it was.

Lumbering around from the south.

Blackdeath .

It stood there, perfectly framed between the two intact hunters’ spires, its whole body so dark that it looked like a silhouette against the purple sky even though it was fully lit.

Galpook heard Foss suck in his breath.

The monster stood, head cocked, eying the scene before it. It seemed confused, perhaps indeed having expected a shovelmouth. But these puny Quintaglios probably looked like tasty morsels, and the bossnosed hornfaces were surely easy pickings. Perhaps the same thought occurred to the bossnoses themselves, for they immediately started jostling each other. Galpook motioned to the riders, and they touched the beasts behind the neck frills in ways meant to calm them.

Of course, all that presupposed that the blackdeath was hungry—which perhaps it was not. The monster tilted its head back and forth, appraising, it seemed, each member of the hunting party, but then after a few beats, it half turned as if to go, as if the Quintaglios and their mounts didn’t sufficiently amuse it.

Galpook leaned back on her tail and yelled.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Fossil Hunter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Fossil Hunter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Fossil Hunter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.