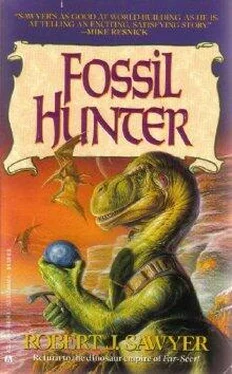

Robert Sawyer - Fossil Hunter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Sawyer - Fossil Hunter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1993, ISBN: 1993, Издательство: Ace Science Fiction, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Fossil Hunter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ace Science Fiction

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- ISBN:0-765-30793-4

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fossil Hunter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Fossil Hunter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

trilogy depicts an Earth-like world on a moon which orbits a gas giant, inhabited by a species of highly evolved, sentient Tyrannosaurs called Quintaglios, among various other creatures from the late cretaceous period, imported to this moon by aliens 65 million years prior to the story.

Fossil Hunter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Fossil Hunter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“But there’s no guarantee that the winner of a battle between just the two of us now would indeed be the same one of the eight who would have best eluded the bloodpriest twenty-eight kilodays ago.”

Rodlox grunted. “True. But in the absence of any alternative method of making the determination, it must suffice. I can prove I am of the imperial line, prove that I am Larsk’s descendant.”

“Proof is an elusive thing—”

“I can demonstrate it to the reasonable satisfaction of the public. And that, fat one, is all that counts.”

A moment later, Dybo’s claws slipped out, and it seemed to Rodlox that it was perhaps a deliberate gesture rather than an instinctive response. “You will not address me that way. My name is Dy-Dybo, and I grant you permission to use it. If you prefer to call me by title, you will use ‘Your Luminance’ or ‘Emperor.’ ”

“I will call you what I wish.”

Dybo raised his hand. “Then this conversation is at an end. I have granted you no special privileges, beyond the right to call me directly by name. I rule, Dy-Rodlox. Acknowledge that.”

“For the time being, Dybo.” That Rodlox had chosen the familiar form of his name visibly irritated Dybo, for it was clearly done not from affection but out of defiance. “But you must answer my challenge.”

Still, Dybo adopted a slightly mollified tone. “I see that you are a person of strong will, and I grant that your intellect is keen.” He scratched his belly, which was spilling over the side of the polished stone slab. “Perhaps Edz’toolar is too barren and isolated a prize for one such as you. I offer an accommodation, a middle ground: a senior official’s role, with whatever portfolio you desire. Public works? The judiciary? Name it, and it is yours. You will move here to the Capital and enjoy all the benefits of life at the imperial court.”

Rodlox scraped his teeth together, a deliberate mockery of laughter. “You are transparent, Dybo. You perceive me as a threat, so you would have me underfoot where I could be watched at all times. I reject your offer. You will fight me in single combat. And I shall win.”

Dybo spoke now as one might speak to a child. “Single combat has been barred since ancient times. You know that. There is no way to begin a battle without having it continue until one participant is dead.”

“That is true.”

“You threaten me with death? There are prescribed penalties for such treason.”

“I make no threat. I simply note the probable outcome of a battle between us.”

“I concede that I am perhaps not your physical match—

“Indeed you are not.”

“But being Emperor is not about physical prowess. It’s about fairness and progress and clarity of vision.”

“Which is why the most appropriate person—the rightful heir— must, must , lie upon that ruling slab that now strains to support you.”

Dybo spread his arms, looking to Rodlox like a monster wingfinger, suspended in air by the slab. “All the Packs are prosperous. We’re making great strides toward the stars. What quarrel do you have with me?”

“I hate you.” The words were unexpectedly harsh.

Dybo’s inner eyelids blinked. “I do not hate you, Rodlox.”

“You should. For I am your downfall personified. I will push and push and push until I am in your place.”

“I could have you banished.”

“To where? Edz’toolar?” Rodlox clicked his teeth. “I am lord of Edz’toolar already.”

“I could have you executed.”

“And violate the ancient laws? I think not. There are those who would not stand for that; you would destroy what’s left of your own authority if you flouted our laws so. No, Dybo, you have only three choices. One”—and here Rodlox raised a finger, claw extended—”you can accept my challenge. Two”—a second finger erect, its claw likewise unsheathed—”you can abdicate your role, acknowledge my claim, and let me assume the Emperorship. I will allow you to live. Or, three”—and a third clawed finger was held up—”you can take the coward’s route and wait until the people force you to respond to my challenge.”

Dybo regarded Rodlox’s raised hand. The ticking off of points with clawed fingers was so like his mother’s way. For the first time, Dybo realized that, without a doubt, this was his brother. It was a tragedy, this conflict, for surely in cooperation they could accomplish so much more than they individually would through a rivalry.

Dybo shook his head. “You are wrong, Rodlox. There is a fourth alternative, and one that is more appropriate than any of your choices. Hear me describe it, and then we shall see which of us is the coward.”

I wish I didn’t have siblings. I try not to compare myself to them, but it’s futile. I can’t help myself. Am I as proficient as they? As keen of mind? Is my pilgrimage tattoo as intricate and well-balanced as that sported by Yabool? And which of us does Novato and Afsan favor? Surely they’ve thought that, if things had gone differently, only one of their children would have lived. Which would they have preferred it to be?

I was thinking these thoughts today as I ate in one of the communal dining halls when Haldan walked in. She passed nowhere near me on her way to fetch a piece of meat, so she didn’t bother to bow concession in my direction. She simply settled herself in at a bench on the opposite side of the room and began to gnaw at her meal.

I watched her. Of course I was careful not to swing my muzzle in her direction; she couldn’t tell where I was looking. But it came to me, as I worried out the final bits of meat adhering to the bone in front of me, that I couldn’t tell where she was looking, either. Her eyes, solid black, could have been focused on the flesh in front of her.

Or they could have been focused on me.

On me.

We’d often thought the same thoughts before; I’d seen it in her expression.

Were we thinking the same thing now?

And suddenly I realized exactly what it was that I was thinking at that moment, a ripple that wouldn’t die down, a thought dark and dangerous and persistent.

I wished she was dead.

I stopped picking over my meat and, at the same moment, she stopped picking over hers.

I wondered if she was thinking the same thing about me.

*16*

Toroca was up on deck. On board a sailing ship, everyone had chores to perform, and Babnol knew she could count on him being occupied for at least a couple of daytenths. She went down the ramp, its timbers groaning not under her weight but rather under the buffeting of the ship, and came to Toroca’s cabin.

She paused briefly to reread the plaque about Afsan and to admire the carving of the five hunters in the dark wood of the door. There was a copper signaling plate adjacent to the doorjamb, but she didn’t drum her claws against it. Instead, she stole a furtive glance over her shoulder, then opened the door, the squeaking of its hinges making her even more nervous. As soon as she was inside Toroca’s cabin, she swung the door shut.

Her claws were exposed. Invading another’s territory was uncomfortable. Although she knew Toroca wouldn’t be back for some time, she couldn’t tarry here. It was too upsetting.

Although there was a desk with a small bench in front of it—space aboard a sailing ship was at too much of a premium to allow for a dayslab—Toroca had wisely placed all fragile objects directly on the floor, lest the pitching of waves knock them off the desk. No lamps were lit, of course; it was far too dangerous to leave a flame unattended. But the leather curtain was drawn back from the porthole, and, indeed, the little window had been swung open, letting the cold, salty air from outside pour in. In the harsh sunlight coming from the porthole, she could see the hinged wooden case that held the far-seer Afsan had given to Toroca. But that was not what she had come for, nor was the object of her quest plainly visible.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Fossil Hunter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Fossil Hunter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Fossil Hunter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.