“I tell you that,” Bilker Moody said, unblinking, “’cause wherever I am, that’s where the heat’s gonna be. You come in, I go out. It’s for your own good.”

“That’s a little melodramatic, isn’t it?”

“You’re the joker got took for that joyride down in the Fork? The one got a cross burned on his lawn?”

“So you’re really expecting trouble?”

“I’m paid to expect it.”

“Then maybe I’d better leave you to your work.”

“’Night,” he said. “And on your way out—”

“Yeah?”

“Don’t let the doorknob ream you in the asshole.”

“Mr. Moody—”

“Call me Bilker.” His eyebrows lifted, maybe to suggest his vulgar parting shot had been intended companionably, maybe to stress the irony of inviting me to use his first name after firing that shot. He raised the Ruger and waved it at the door.

“Good night, Bilker. Really enjoyed our chat.”

The next morning, I told RuthClaire about this exchange, as nearly verbatim as I could make it. She said I’d made a skeptical convert of Bilker. The proof of his good opinion was that he never joked with incorrigible turds, only those who struck him as recyclable into relatively fragrant human beings. Thanks a lot, I said. But I settled for it. It was better than getting fragged in my sleep….

RuthClaire and Adam had a downstairs studio, once a living room and parlor. Previous occupants had knocked out the wall, though, and now you had elbow room galore down there. In this vast space were unused canvases, stretching frames, makeshift easels, and even a sheet of perforated beaverboard with pegs and braces for hanging art supplies and tools. Elsewhere, finished and half-finished paintings leaned against furniture, reposed in untidy stacks, or vied for attention on the only wall where the artists had thought enough of their work to display it as if in a gallery.

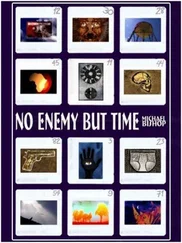

“No more plate paintings,” RuthClaire told me the night after my visit to Bilker. “I’m off in a new direction. Wanna see?”

Of course I did. RuthClaire led me to a stack of canvases near a table consisting of three sawhorses capped by a sheet of plywood. All the paintings were small, no larger than three feet by four, most only a foot or two on their longest sides. RuthClaire had painted them in drab washed-out acrylics. They weren’t quite abstract, but neither were they representational—an ambiguity they shared with Adam’s bigger, bolder canvases.

To me, in fact, RuthClaire’s new paintings looked like preliminaries for paintings she had not yet essayed in final form. That she considered them finished, and regarded them with undiluted enthusiasm, astonished me. I wondered what to say. M.-K. Kander’s photographs had at least given me the verbal ammunition of my outrage. Here, though, was little to comment on: murky beige or green backgrounds in which many anonymous shapes swam.

“Well?” Then, noting my hesitation, she said, “Come on. Your honest reaction, Paul—the only kind that’s worth a flip.”

“The honest reaction of a chef probably isn’t worth even that, Ruthie Cee.”

“Oh, come on. You’ve got good art sense.”

“Let me off the hook.”

“You don’t like them?”

“If I’d crayoned stuff like this in Mrs. Stanley’s fourth-grade class in Tocqueville, she’d have said I was wasting paper. That honest enough for you?”

As if I’d yanked an invisible bridle, my ex’s nostrils flared. But she recovered and asked me why Mrs. Stanley would have made such a harsh judgment.

“For muddying the colors.”

“The muddiness is deliberate, Paul.”

I said that, as a consequence, these paintings looked anemic, downright blah.

“That’s an unconsidered first impression.”

“I’ve been staring at them a good five minutes.”

“A gnat’s eyeblink. Maybe you should live with one a while. Pick out the one you hate the least—or hate the most, for that matter—and take it home with you.”

I sighed. RuthClaire’s pitiful acrylics belonged on a bonfire. Even Paleolithic cave art—the least rather than the most polished examples—outshone these hazy windows on my ex’s soul. In the nearly ten years I’d known her, I’d never seen her do less challenging or attractive work. It was hard to believe that living with one of these paintings would heighten my appreciation of it or any of the others.

She began to explain what she was up to: freeing the work of pretense. Bright colors had a primitive appeal that rarely engaged the intellect. She was after a subtler means of capturing her audience. Artists had to risk alienating their audience—not with violence, sacrilege, or pornography, but with the unfamiliar, the understated, and the ambiguous—in order to make their art new . Viewers with the patience and the openness to outwait their first negative reactions would see what she was trying to do.

“But what if the paintings are bad , kiddo—banal, lackluster, and ugly?”

“Then they’ll never enlighten you, no matter how long you hang around them. Eventually, your negative reactions will be vindicated.” Quickly, though, she hedged this point: “Or maybe you’re just color-blind or tone-deaf to the work’s real merit.”

“I know spoiled pork when I smell it. I don’t have to eat it to know it’s bad.”

“A gourmet chef is a gourmet chef is a glorified short-order cook. An artist is an artist is an artist.”

“That’s smug, RuthClaire, disgustingly smug.”

She kissed my cheek. “You’ve noticed how small they are?”

“A point in their favor.”

“Another way to free them from pretense,” she said. “Rothko liked big paintings because the viewer has to climb into them and participate physically in their energy and movement. Well, I want the viewer to climb into these canvases intellectually—not in the clinical way a Mondrian demands, but in the spiritual way a decision for faith requires.”

“You want the viewer to take the merit of these paintings on faith ?”

“I call the series Souls , Paul.”

“And that, of course, explains everything.”

At this juncture, RuthClaire good-humoredly decided to end the argument. Never had we been so badly at odds on the subject of her art, and never had our disagreement on the subject had less effect on our good opinion of the other: weird.

“Let’s go see Adam,” she said.

That afternoon I left the hospital with T. P.—to give Adam and RuthClaire time together alone. Our destination was a recently remodeled restaurant called Everybody’s. It served beer, sandwiches, pizza, salads, and pasta in an airy, relaxed atmosphere perfectly suited to its mostly college-connected clientele.

I ordered beer and a bacon-cheeseburger, but a Coke and a cheeseburger for my temporary ward. T. P. sat in a kiddie chair with a booster seat, and we whiled away forty-five minutes eating and watching people. Traffic plied the hill on North Decatur Road, squirrels scampered across the dappled campus, and emerald-necked pigeons strutted the sidewalks. I felt loose and at ease, almost ready to drowse. Staring into my beer, I may have actually done so.

And then someone stood beside T. P. under Everybody’s angled skylights. I almost spilled my beer reacting to her presence.

Before I could stand up, though, she sat down on the chair opposite mine. “Hello, Mr. Loyd. I recognized you from newspaper photos. The baby’s being here didn’t hurt, though. That made me look twice. Otherwise, I’d have walked on by.”

“Another tribute to my personal magnetism.”

The woman gave me a look of amiable amusement. I figured her to be in her early thirties— almost out of the range of my interest. Thin-boned and tall, she escaped looking angular. Springy amber ringlets framed her face. She wore a gold-plated necklace that seemed to be made up of dozens of minuscule glittering hinges. She folded her arms on the table, and the amber down prickling them caught the evanescent dazzle of the tiny hinges at her throat.

Читать дальше