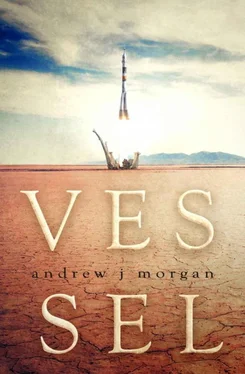

‘Two hundred and fifty seconds. Roll is nominal. Stage two core booster separation. Third stage ignition.’

‘Stage three engines nominal.’

‘Copy.’

‘Three hundred and twenty seconds. Structural parameters are nominal.’

Gardner continued prodding buttons with his stick. Sally was impressed by how calm he’d been. If he felt nervous, neither his voice nor his actions revealed it.

‘Third stage engines are stable.’

‘Four hundred seconds, four zero zero. Everything is nominal.’

‘Copy, loud and clear.’

‘Four hundred and thirty seconds, four three zero.’

‘Still with us, Fisher?’

‘I sure am. Feeling great!’

She let out a whoop. Probably against protocol, but what did she care?

Gardner laughed. ‘That’s the spirit.’

‘Five hundred seconds. Glad you’re having fun, Fisher. Pitch and roll nominal.’

‘Separation.’

‘Copy, third stage separation.’

Progress, now stripped of the rocket that launched it, had reached a stable velocity of 13,421 miles per hour. The number had seemed meaningless in books and on the internet, but now it made perfect sense. As the ferocious g-forces abated, an invisible hand pushed up through her abdomen, a sensation that reminded her of driving over a humpback bridge too fast.

‘We’re standing by for docking proximity to the International Space Station,’ Aleks said. ‘That’ll be in about six hours. Congratulations Progress M Eighteen M, and thank you for a great flight.’

‘Copy, speak soon, and thank you,’ Gardner replied. ‘Phew. Quite a flight, huh, Sally?’

‘You’re telling me,’ she said. The repeated realisation of where she was gave her sparks of excitement, making her grin with uncontrollable glee. It gave her a strange feeling of alertness, a new level of being that buzzed through her core. She was glad Gardner couldn’t see her face, because she was probably pulling some ridiculous expressions. ‘What do we do now?’

‘We sit and wait. Progress will automatically deploy all its sensors and antennas, make a few changes to the pitch and roll. All we need to do is kick back for six hours and wait to dock with the ISS.’

‘As easy as that? Don’t you have to dock us yourself?’

‘Nope. Automatic.’

‘How much do they pay you?’

Gardner laughed. ‘I’m not here for when it goes right.’

Gardner’s words hung like a sour mist in the fresh silence. Sally remembered what Bales had said about the crew of the ISS, that she might need protection from them. Unease doused her elation. Gardner must have picked up on her dipping mood, because he fired up a different conversation altogether.

‘So, you’re a communications expert, right?’

‘Yeah.’

‘The best?’

‘Apparently.’

‘Well, for a communications expert you sure are difficult to communicate with…’

Gardner laughed at his own joke; Sally didn’t. ‘I didn’t mean anything by it,’ he said. ‘Just a bit of humour. That’s all.’

Sally gazed out at the moving stars, watching each burn with more brilliance than the last. ‘What do you think’s waiting for us there?’

‘At the ISS? Some folks who’ll be pleased for some new company I expect. Being an astronaut is lonely business, even when you’re with others. Some spend years at a time up here.’

‘Coming back to Earth must be strange after that long.’

‘That’s what they say.’

‘What’s the longest you’ve stayed up here for?’

Gardner thought about it for a moment. ‘Six months, I think it was. Yeah, six months.’

‘How did you find it when you came back?’

‘It was hard to walk what with all the muscular atrophy,’ Gardner said, chuckling.

‘No, I mean, how did you find it mentally ? You said you found god up here. Did that change who you were when you came back?’

Gardner stayed silent.

‘Is that why you haven’t been up here for so long?’

‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘Come on — TMA Eight was seven years ago. What happened? Why are you up here with me now?’

‘What use are all these questions? We’re up here now. Nothing’s going to change that.’

Realising that six hours was a long time and that it wasn’t the best idea to cross the man sent to protect her, Sally stopped asking questions, even as they continued to burn a hole in her mind. Before long, Gardner was back to his usual chirpy self, laughing and joking about any and every subject — except the mission. He may have been avoiding the topic, but it was all Sally could think of.

* * *

‘Jacob here.’

‘Sean! How did the launch go? Got anything for me?’

The muffled voice coming from the satellite phone was difficult to make out, but not impossible.

‘She was on board, I know it.’

‘So you were right. Well done. What proof do you have?’

‘They flew her in yesterday. She’s got to be on board.’

‘What’s NASA saying?’

‘Well, NASA’s still talking about some kind of space storm. They’re denying Sally’s involvement completely.’

‘And you don’t believe them?’

‘Hell, no. Why send a communications expert — from SETI no less — to look at some space weather?’

‘Why indeed.’

‘And not only that, but guess who they’ve got going up with her?’

‘I give up. Who?’

‘Robert Gardner.’

‘Of TMA Eight?’ the satellite phone said, after a pause.

‘The very same.’

* * *

Sally attempted to shuffle in her seat, but the harnesses restricted even the slightest movement.

‘Are you uncomfortable?’ Gardner asked.

‘I’m fine. I just need to… go.’

‘Then go. You’ve got your MAG on. They don’t call it maximum absorbency for nothing.’

Sally wrinkled her nose at the thought. She may have been wearing a diaper, but she sure as hell wasn’t going to use it.

‘If it’s any help,’ Gardner said, ‘I’ve been in mine.’

‘That’s disgusting. How long until we reach the ISS?’

‘About three-quarters of an hour.’

‘I’ll wait, thanks.’

She curled her toes, trying to think of anything but the need to urinate. The feeling passed, and before she knew it Aleks’ voice came crackling over the radio.

‘Progress M Eighteen M, TsUP. First stage of docking approach underway, range, three zero zero zero metres. How are you doing?’

‘Copy TsUP. We’re both doing great,’ Gardner responded. ‘Switching to docking camera.’

Gardner reached with his metal rod and pushed a button on the instrument panel. A small screen illuminated. In the middle was the ISS, a white smear against the blackness of space.

‘Viewfinder looking good. Approach is nominal.’

The white smear grew bigger, consuming the screen a pixel at a time.

‘Range, one thousand metres, one zero zero zero. Engaging Kurs automated rendezvous sequence.’

‘Copy.’

The smear, which had been drifting down, veered back to centre. As it did, a flash of white enveloped the screen, falling back to nothing but grinding static.

‘TsUP, TsUP, loss of visual, repeat, loss of visual.’

A trace of nerves strained Gardner’s voice.

‘Copy, loss of visual. Standby.’

Sally realised that the pulsing noise coming through the headset wasn’t coming through the headset at all; it was coming from her head, as blood flushed through at an ever-rising rate. The seconds ticked by as minutes, each one further from home.

‘Progress M Eighteen M, we’ve lost all visual down here too. Kurs downlink failed. Proceed to manual rendezvous sequence.’

Gardner’s response was slow.

Читать дальше