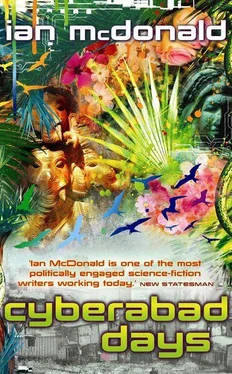

Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cyberabad Days

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-591-02699-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cyberabad Days: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cyberabad Days»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); a new, muscular superpower in an age of artificial intelligences, climate-change induced drought, strange new genders, and genetically improved children.

Cyberabad Days — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cyberabad Days», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Thacker has a small, professional bar in his kitchen annexe. Esha does not know drink so the chota peg she makes herself is much much more gin than tonic but it gives her what she needs to clean the sour, biley vomit from the wool rug and ease the quivering in her breath.

Esha starts, freezes, imagining Rao’s voice. She holds herself very still, listening hard. A neighbour’s tivi, turned up. Thin walls in these new-build executive apartments.

She’ll have another chota peg. A third and she can start to look around. There’s a spa-pool on the balcony. The need for moving, healing water defeats Thacker’s warnings. The jets bubble up. With a dancer’s grace she slips out of her clinging, emotionally soiled clothes into the water. There’s even a little holder for your chota peg. A pernicious little doubt: how many others have been here before me? No, that is his kind of thinking. You are away from that. Safe. Invisible. Immersed. Down in Sisganj Road the traffic unravels. Overhead the dark silhouettes of the scavenging kites and, higher above, the security robots, expand and merge their black wings as Esha drifts into sleep.

‘I thought I told you to stay away from the windows.’

Esha wakes with a start, instinctively covers her breasts. The jets have cut out and the water is long-still, perfectly transparent. Thacker is blue-chinned, baggy-eyed and sagging in his rumpled gritty suit.

‘I’m sorry. It was just, I’m so glad, to be away… you know?’

A bone-weary nod. He fetches himself a chota peg, rests it on the arm of his sofa and then very slowly, very deliberately, as if every joint were rusted, undresses.

‘Security has been compromised on every level. In any other circumstances it would constitute an i-war attack on the nation.’ The body he reveals is not a dancer’s body; Thacker runs a little to upper body fat, muscles slack, incipient man-tits, hair on the belly hair on the back hair on the shoulders. But it is a body, it is real. ‘The Bharati government has disavowed the action and waived Aeai Rao’s diplomatic immunity.’

He crosses to the pool and restarts the jets. Gin and tonic in hand, he slips into the water with a bone-deep, skin-sensual sigh.

‘What does that mean?’ Esha asks.

‘Your husband is now a rogue aeai.’

‘What will you do?’

‘There is only one course of action permitted to us. We will excommunicate him.’

Esha shivers in the caressing bubbles. She presses herself against Thacker. She feels him, his man-body moving against her. He is flesh. He is not hollow. Kilometres above the urban stain of Delhi, aeaicraft turn and seek.

The warnings stay in place the next morning. Palmer, home entertainment system, com channels. Yes, and balcony, even for the spa.

‘If you need me, this palmer is department-secure. He won’t be able to reach you on this.’ Thacker sets the glove and ’hoek on the bed. Cocooned in silk sheets, Esha pulls the glove on, tucks the ’hoek behind her ear.

‘You wear that in bed?’

‘I’m used to it.’

Varanasi silk sheets and Kama Sutra prints. Not what one would expect of a Krishna Cop. She watches Thacker dress for an excommunication. It’s the same as for any job – ironed white shirt, tie, hand-made black shoes – never brown in town – well polished. Eternal riff of bad aftershave. The difference: the leather holster slung under the arm and the weapon slipped so easily inside it.

‘What’s that for?’

‘Killing aeais,’ he says simply.

A kiss and he is gone. Esha scrambles into his cricket pullover, a waif in baggy white that comes down to her knees, and dashes to the forbidden balcony. If she cranes over, she can see the street door. There he is, stepping out, waiting at the kerb. His car is late, the road is thronged, the din of engines, car horns and phatphat klaxons has been constant since dawn. She watches him wait, enjoying the empowerment of invisibility. I can see you. How do they ever play sport in these things? she asks herself, skin under cricket pullover sweaty and sticky. It’s already thirty degrees, according to the weather ticker across the foot of the video-silk shuttering over the open face of the new-build across the street. High of thirty-eight. Probability of precipitation: zero. The screen loops Town and Country for those devotees who must have their soapi, subtitles scrolling above the news feed.

Hello Esha, Ved Prakash says, turning to look at her.

The thick cricket pullover is no longer enough to keep out the ice.

Now Begum Vora namastes to her and says, I know where you are, I know what you did.

Ritu Parvaaz sits down on her sofa, pours chai and says, What I need you to understand is, it worked both ways. That ’ware they put in your palmer, it wasn’t clever enough.

Mouth working wordlessly; knees, thighs weak with basti girl superstitious fear, Esha shakes her palmer-gloved hand in the air but she can’t find the mudras, can’t dance the codes right. Call call call call.

The scene cuts to son Govind at his racing stable, stroking the neck of his thoroughbred uber-star Star of Agra. As they spied on me, I spied on them.

Dr Chatterji in his doctor’s office. So in the end we betrayed each other.

The call has to go through department security authorisation and crypt.

Dr Chatterji’s patient, a man in black with his back to the camera turns. Smiles. It’s A. J. Rao. After all, what diplomat is not a spy?

Then she sees the flash of white over the rooftops. Of course. Of course. He’s been keeping her distracted, like a true soapi should. Esha flies to the railing to cry a warning but the machine is tunnelling down the street just under power-line height, wings morphed back, engines throttled up: an aeai traffic monitor drone.

‘Thacker! Thacker!’

One voice in the thousands. And it is not hers that he hears and turns towards. Everyone can hear the footsteps of his own death. Alone in the hurrying street, he sees the drone pile out of the sky. At three hundred kilometres per hour it takes Inspector Thacker of the Department of Artificial Intelligence Registration and Licensing to pieces. The drone, deflected, ricochets into a bus, a car, a truck, a phatphat, strewing plastic shards, gobs of burning fuel and its small intelligence across Sisganj Road. The upper half of Thacker’s body cartwheels through the air to slam into a hot samosa stand.

The jealousy and wrath of djinns.

Esha on her balcony is frozen. Town and Country is frozen. The street is frozen, as if on the tipping point of a precipice. Then it drops into hysteria. Pedestrians flee; cycle rickshaw drivers dismount and try to run their vehicles away; drivers and passengers abandon cars, taxis, phatphats; scooters try to navigate through the panic; buses and trucks are stalled, hemmed in by people.

And still Esha Rathore is frozen to the balcony rail. Soap. This is all soap. Things like this cannot happen. Not in the Sisganj Road, not in Delhi, not on a Tuesday morning. It’s all computer-generated illusion. It has always been illusion.

Then her palmer calls. She stares at her hand in numb incomprehension. The department. There is something she should do. Yes. She lifts it in a mudra – a dancer’s gesture – to take the call. In the same instant, as if summoned, the sky fills with gods. They are vast as clouds, towering up behind the apartment blocks of Sisganj Road like thunderstorms; Ganesh on his rat vahana with his broken tusk and pen, no benignity in his face; Siva, rising high over all, dancing in his revolving wheel of flames, foot raised in the instant before destruction, Hanuman with his mace and mountain fluttering between the tower blocks: Kali, skull-jewelled, red tongue dripping venom, scimitars raised, bestrides Sisganj Road, feet planted on the rooftops.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cyberabad Days» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.