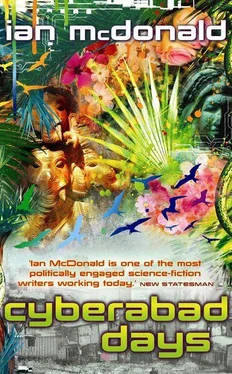

Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cyberabad Days

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-591-02699-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cyberabad Days: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cyberabad Days»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); a new, muscular superpower in an age of artificial intelligences, climate-change induced drought, strange new genders, and genetically improved children.

Cyberabad Days — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cyberabad Days», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All of India had been invited and all of India had come, in flesh and in avatar. People rose, applauding. Cameras swooped on ducted fans. My nutes, my family from the Hijra Mahal, had been given seats at row ends.

‘How could I improve on perfection?’ said Dahin the face doctor as my bare feet trod rose petals towards the dais.

‘The window, the wedding!’ said Sul. ‘And, pray the gods, many many decades from now, a very old and wise widow.’

‘The setting is nothing without the jewel,’ exclaimed Suleyra Party Arranger, throwing pink petals into the air.

I waited with my attendants under the awning as Salim’s retainers crossed the courtyard from the men’s quarters. Behind them came the groom on his pure white horse, kicking up the rose petals from its hooves. A low, broad ooh went up from the guests, then more applause. The maulvi welcomed Salim onto the platform. Cameras flocked for angles. I noticed that every parapet and carving was crowded with monkeys – flesh and machine – watching. The maulvi asked me most solemnly if I wished to be Salim Azad’s bride.

‘Yes,’ I said, as I had said the night when I first accepted his offer. ‘I do, yes.’

He asked Salim the same question, then read from the Holy Quran. We exchanged contracts, our assistants witnessed. The maulvi brought the silver plate of sweetmeats. Salim took one, lifted my gauze veil and placed it on my tongue. Then the maulvi placed the rings upon our fingers and proclaimed us husband and wife. And so were our two warring houses united, as the guests rose from their seats cheering and festival crackers and fireworks burst over Jaipur and the city returned a roaring wall of vehicle horns.

Peace in the streets at least. As we moved towards the long, cool pavilions for the wedding feast, I tried to catch Heer’s eye as yt paced behind Salim. Yts hands were folded in the sleeves of yts robes, yts head thrust forward, lips pursed. I thought of a perching vulture.

We sat side by side on golden cushions at the head of the long, low table. Guests great and good took their places, slipping off their Italian shoes, folding their legs and tucking up their expensive Delhi frocks as waiters brought vast thalis of festival food. In their balcony overlooking the diwan, musicians struck up a Rajput piece older than Jaipur itself. I clapped my hands. I had grown up to this tune. Salim leaned back on his bolster.

‘And look.’

Where he pointed, men were running up the great sun-bird-man kite of the Jodhras. As I watched, it skipped and dipped on the erratic winds in the court, then a stronger draught took it soaring up into the blue sky. The guests went oooh again.

‘You have made me the happiest man in the world,’ Salim said.

I lifted my veil, bent to him and kissed his lips. Every eye down the long table turned to me. Everyone smiled. Some clapped.

Salim’s eyes went wide. Tears suddenly streamed from them. He rubbed them away and when he put his hands down, his eyelids were two puffy, blistered boils of flesh, swollen shut. He tried to speak but his lips were bloated, cracked, seeping blood and pus. Salim tried to stand, push himself away from me. He could not see, could not speak, could not breath. His hands fluttered at the collar of his gold-embroidered sherwani.

‘Salim!’ I cried. Leel was already on yts feet, ahead of all the guest doctors and surgeons as they rose around the table. Salim let out a thin, high-pitched wail, the only scream that would form in his swollen throat. Then he went down onto the feast table.

The pavilion was full of screaming guests and doctors shouting into palmers and security staff locking the area down. I stood useless as a butterfly in my make-up and wedding jewels and finery as doctors crowded around Salim. His face was like a cracked melon, a tight bulb of red flesh. I swatted away an intrusive hovercam. It was the best I could do. Then I remember Leel and the other nutes taking me out into the courtyard where a tilt-jet was settling, engines sending the rose petals up in a perfumed blizzard. Paramedics carried Salim out from the pavilion on a gurney. He wore an oxygen rebreather. There were tubes in his arms. Security guards in light-scatter armour pushed the great and the celebrated aside. I struggled with Leel as the medics slid Salim into the tilt-jet but yt held me with strange, withered strength.

‘Let me go, let me go, that’s my husband…’

‘Padmini, Padmini, there is nothing you can do.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Padmini, he is dead. Salim your husband is dead.’

Yt might have said that the moon was a great mouse in the sky.

‘Anaphylactic shock. Do you know what that is?’

‘Dead?’ I said simply, quietly. Then I was flying across the court toward the tilt-jet as it powered up. I wanted to dive under its engines. I wanted to be scattered like the rose petals. Security guards ran to cut me off but Leel caught me first and brought me down. I felt the nip of an efuser on my arm and everything went soft as the tranquilizer took me.

After three weeks I called Heer to me. For the first week the security robots had kept me locked back in the zenana while the lawyers argued. I spent much of that time out of my head, part grief-stricken, part insane at what had happened. Just one kiss. A widow no sooner than I was wed. Leel tended to me, the lawyers and judges reached their legal conclusions. I was the sole and lawful heir of Azad-Jodhra Water. The second week I came to terms with my inheritance: the biggest water company in Rajputana, the third largest in the whole of India. There were contracts to be signed, managers and executives to meet, deals to be set up. I waved them away, for the third week was my week, the week in which I understood what I had lost. And I understood what I had done, and how, and what I was. Then I was ready to talk to Heer.

We met in the diwan, between the great silver jars that Salim, dedicated to his new tradition, had kept topped up with holy Ganga water. Guard-monkeys kept watch from the rooftops. My monkeys. My diwan. My palace. My company, now. Heer’s hands were folded in yts sleeves. Yts eyes were black marble. I wore widow’s white – a widow, at age fifteen.

‘How long had you planned it?’

‘From before you were born. From before you were even conceived.’

‘I was always to marry Salim Azad.’

‘Yes.’

‘And kill him.’

‘You could not do anything but. You were designed that way.’ Always remember , my father had said, here among these cool, shady pillars, you are a weapon . A weapon deeper, subtler than I had ever imagined, deeper even than Leel’s medical machines could look. A weapon down in the DNA: designed from conception to cause a fatal allergic reaction in any member of the Azad family. An assassin in my every cell, in every pore and hair, in every fleck of dust shed from my deadly skin.

I killed my beloved with a kiss.

I felt a huge, shuddering sigh inside me, a sigh I could never, must never utter.

‘I called you a traitor when you said you had always been a loyal servant of the House of Jodhra.’

‘I was, am and will remain so, please God.’ Heer dipped yts hairless head in a shallow bow. Then yt said, ‘When you become one of us, when you step away, you step away from so much; from your own family, from the hope of ever having children… You are my family, my children. All of you, but most of all you, Padmini. I did what I had to for my family, and now you survive, now you have all that is yours by right. We don’t live long, Padmini. Ours lives are too intense, too bright, too brilliant. There’s been too much done to us. We burn out early. I had to see my family safe, my daughter triumph.’

‘Heer…’

Yt held up a hand, glanced away, I though I saw silver in the corners of those black eyes.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cyberabad Days» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.