Judge Herrington’s little mouth smiled at this.

“Fine,” said Lopez. “What we need now is your PIN, so that we can complete the transaction.”

Karen folded her arms across her chest. “And I don’t believe the court can make me divulge that.”

“No, no, of course not. Privacy is important. May I?” Lopez held out her hand for the terminal, and Karen gave it to her. She stabbed out some numbers on the unit, then handed it back to Karen. “Would you read what it says?”

Karen’s plastic face wasn’t quite as pliable as one made out of flesh was, but I could see the consternation. “It says, ‘PIN OK.’ ”

“Well, what do you know!” declared Lopez. “Without using your fingerprint, or your retinal pattern, or any knowledge known solely to you, we’ve managed to access your account, haven’t we?”

Karen said nothing.

“Haven’t we, Ms. Bessarian?”

“Apparently.”

“Well, in that case, why don’t we go ahead and transfer ten dollars into my account, just as you did for Mr. Draper?”

“I’d rather not,” said Karen.

“What?” said Lopez. “Oh, I see. Yes, of course, you’re right. That’s totally unfair. After all, Mr. Draper gave you ten dollars first. So, I suppose I should also give you a Reagan.” She reached into her jacket pocket again, brought out her hand, and proffered a coin.

Karen crossed her arms in front of her chest, refusing to take it.

“Ah, well,” said Lopez, peeling back the gold foil, revealing the embossed chocolate disk inside. She popped it in her mouth, and chewed. “This one’s a fake, anyway.”

A gilded cage is still a cage.

I was fine now, with decades of life ahead of me. And I didn’t want to spend it here at High Eden.

And—I was fine, wasn’t I? I mean, Chandragupta’s technique had supposedly cured me. But…

But my head was still throbbing. It came and it went, thank God; I couldn’t take it if it was like this all the time, but…

But nothing was helping. Not for long, not for good.

And I didn’t trust the doctors here. I mean, look at what had happened to poor Karen! Code Blue my ass…

And yet—

And yet, I had to do something . I wasn’t a machine, a robot. I wasn’t like that other me, that doppelganger, free from aches and pains. My head hurt. When it was happening, it hurt so fucking much.

I left my suite, bouncing along in the lunar gravity, heading for the hospital.

Our next witness was Andrew Porter, who had come down from Toronto, joining the half-a-dozen Immortex suits already here. “Dr. Porter,” said Deshawn, “what is your educational background?”

The witness stand was a little small for someone of Porter’s height, but he scrunched his legs sideways. “I have a Ph.D. in cognitive science from Carnegie Mellon University, as well as Master’s degrees in both Electrical Engineering Science and Computer Studies from CalTech.”

“Have you had any academic appointments?”

Porter’s eyebrows were working, as always. “Several. Most recently I was a senior research fellow with the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.”

“Now, I rather enjoyed Ms. Lopez’s coin trick earlier,” said Deshawn. “But I understand you have a real gold medallion, isn’t that right?”

“Yes, I do. Or, at least, I’m part of the team it belongs to.”

“Did you bring it with you? May we see it?”

“Certainly.”

Porter pulled a large case out of his jacket pocket, and opened it.

“Plaintiff’s three, your honor,” said Deshawn.

There was the usual back-and-forth, then the exhibit was admitted. Deshawn held the medallion up to a camera, showing first one side then the other; the images were projected on the wall screen behind Porter. One side showed a three-quarters view of a young man with delicate features, and was inscribed with the italic quotation, “Can Machines Think?” and the name Alan M. Turing. The other side showed a bearded man with glasses and the name Hugh G. Loebner. Both sides were labeled “Loebner Prize” in letters following the curving edge of the disk.

“How did you come by this?” asked Deshawn.

“It was awarded to us for being the first group ever to pass the Turing Test.”

“And how did you do that?”

“We precisely copied a human mind—that of one Seymour Wainwright, also formerly of MIT—into an artificial brain.”

“And do you continue to work in this area?”

“I do.”

“Who is your current employer?”

“I work for Immortex.”

“In what capacity?”

“I’m the senior scientist. My exact job title is Director, Reinstantiation Technologies.”

Deshawn nodded. “And how would you describe what it is you do in your job?”

“I oversee all aspects of the process of transferring personhood from a biological mind into a nanogel matrix.”

“Nanogel matrix being the material you fashion artificial brains out of?” said Deshawn.

“Correct.”

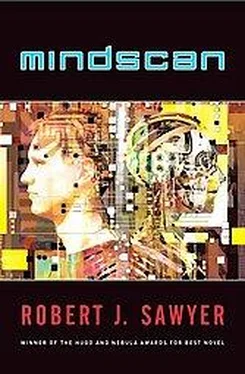

“So, you are one of the developers of the Mindscan process that Immortex uses to transfer consciousness, and you continue to oversee the transference work that Immortex does today, correct?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then,” said Deshawn, “can you explain for us how it is that the human brain gives rise to consciousness?”

Porter shook his long head. “No.”

Judge Herrington frowned. “Dr. Porter, you are required to answer. I don’t want to hear any nonsense about trade secrets, or—”

Porter tried to swivel in his chair, but couldn’t really manage it. “Not at all, your honor. I can’t answer the question because I don’t know what the answer is. No one does, in my opinion.”

“Let me get this straight, Dr. Porter,” asked Deshawn. “You don’t know how consciousness works.”

“That’s right.”

“But nonetheless you can replicate it?” said Deshawn.

Porter nodded. “And that’s all I can do.”

“How do you mean?”

Porter did a good job of looking as though he was trying to decide where to begin, although, of course, we had rehearsed his testimony over and over again. “For over a century now, computer programmers have been trying to duplicate the human mind. Some thought it was a matter of getting the right algorithms, some thought it was a matter of mathematically simulating neural nets, some thought it had something to do with quantum computing. None succeeded. Oh, there are lots of computers around that can do very clever things, but no one has ever built one from scratch that is self-aware in the way you and I are, Mr. Draper. Not once, for instance, has a manufactured computer spontaneously said, ‘Please don’t turn me off.’ Never has a computer spontaneously mused upon the meaning of life. Never has a computer written a bestselling novel. We thought we’d be able to make machines do all those things, but, so far, we can’t.” He looked at the jury, then back at Deshawn. “But the transfers of biological minds that we have produced can do all those things, and more. They are capable of every mental feat that other humans can perform.”

“You say other humans?” asked Deshawn. “You consider the copies to be human?”

“Absolutely. As that medallion proves, they totally, completely, and infallibly pass the Turing Test: there is no question you can ask them that they don’t answer indistinguishably from how other humans answer. They are people.”

“And are they conscious?”

“Absolutely. As conscious as you or I. Indeed, although the voltages differ, the electrical signature of a copied brain and an original brain are the same on properly calibrated EEGs.”

Читать дальше