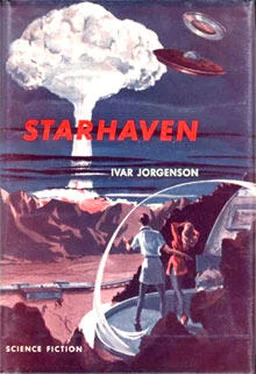

Starhaven

by Robert Silverberg

Johnny Mantell

He was a man with a past—but he didn’t quite know what it was!

Myra Butler

Hers was the most surprising reason of all for living on infamous Starhaven.

Ben Thurdan

Already the supreme ruler of his own world, he sought the gift of the gods—immortality.

Erik Harmon

He held the future of Starhaven in the palm of his hand.

Leroy Marchin

Against Thurdan’s might, his only armor was his courage.

Commander Whitestone

He had launched a secret weapon no man knew how to control.

It was a secluded part of the beach, and the corrugated metal shack was set some distance back from the shimmering tideless sea, close to a grove of green and purple trees. Inside the shack, the man who called himself Johnny Mantell lay on his thin cot. He groaned in his sleep, then abruptly awakened. With Mantell, there was no dim half-world of drowsy transition. At once he was awake and thoroughly alive. Alive—but for how long?

He stepped to the washstand that he’d made and looked at his face in the fragment of mirror nailed over the basin.

The tired, thirtyish face of a man who had been on the toboggan slide to nowhere for too many years stared back at him. His eyes, alight with intelligence though they were, bore the timid, defeated look of an outcast. His face was deeply tanned from roaming the beaches in this part of the planet Mulciber, “Vacation Paradise of the Universe,” as the advertisements proclaimed on the planets of the Galactic Federation, of which Earth was the capital.

Strange, he thought. He could see no change from the way he looked yesterday. Yet there had been a change, and a major one. Up to early this morning, he had been a beachcomber, managing to survive by selling brightly colored shells to tourists, as he had been doing for the past seven years.

But today, the day he had to leave Mulciber, he was a different man.

He was a fugitive from the law. He was a hunted killer.

In his own mental image, Mantell had always thought of himself as being a reasonably law-abiding man; one who held respect for the rights of others, not out of fear but through innate decency; it was, in fact, about the last thing he had—a small measure of his self-respect that a good many of the others seemed to lack. Just an average, decent sort of Joe who never went out of his way looking for trouble, but didn’t let people push him around, either.

But this time he was really being pushed. And there was no way to push back.

Almost ever since he had arrived on Mulciber, Man-tell had been putting off his departure, delaying because there was no special reason to go anywhere. Here, life was easy; by wading out a few yards into the quiet warm sea, all sorts of delicious fish and crustaceans could be caught by net or by hand. Nutritive fruits of many flavors grew on the trees all year round. There were no responsibilities here, except the basic one of keeping yourself alive. But it had come down to just that.

If Mantell wanted to stay alive any longer, he’d have to move fast. Right now. And to do it, he’d have to add one more criminal mark to his new record. He’d have to steal a spaceship. He knew where to go for sanctuary.

Starhaven.

Mike Bryson, one of the other beachcombers on Mulciber, had told Mantell about Starhaven. That had been years ago, back before the time the mudshark had sliced Bryson in half while he was wading for pearl oysters, firyson had said, “Some day, when I get up the incentive, I’m going to steal a ship and light out for Starhaven, Johnny.”

“Starhaven? What’s that?”

Biyson smiled, screwing up his face and showing his yellowed teeth. “Starhaven’s a planet of a red super-giant sun called Nestor. It’s an artificial sort of planet, built twenty or twenty-five years ago by a fellow, name of Ben Thurdan.” Bryson lowered his voice. “It’s a sanctuary for people like us, Johnny. People who couldn’t make the grade or fit in with organized society. Drifters and crooks and has-beens can go to Starhaven, and get decent jobs and live in peace. It’s the place for me, and one day I’m going to get there.”

But Mike Bryson never did make it, Mantell recalled. He tried to remember how long ago it had been that they had brought Bryson’s bleeding body back from the beach. Three years? Four?

Mantell cradled his head in his hands and tried to think. It was hard to sort out the years. There were times when he could hardly remember the day before yesterday, and all his memories seemed like dreams. There were other times when it was all crystal-clear, when he could see all the way back across the years to the time when he had lived on Earth. He had been making the grade in society then.

As a twenty-four-year-old technician at Klingsan Defense Screens, for a while everything seemed to roll along well. Then he really got on the beam—or so he thought. Enthusiasm, energy seemed to exude from his pores. A latent inventive streak suddenly emerged in him. He knew his stuff all right; maybe too well.

Trouble was that his abounding faith in himself and in his innovations made him appear cocky, and his inventions, while basically sound, needed refinements to be practical. At the time the Klingsan plants were not geared to machine them. It would take special heavy presses of a new amalgam of metals; specially made dies as well as new electronic devices. All that represented an impressive outlay of capital. So, perhaps, if Johnny would work over his designs for a couple of years, then they could be presented to the board of directors, and . . .

Johnny, furious, told off his employers. He got another job in a similar plant, but became quarrelsome and edgy when they, too, decided not to produce his inventions. And then he thought he found the answer to his frustrations. If a drink or two would relax him in the evening, then four or six would do the job better. They did, all right. Soon he was working on a quart a day.

He drank himself right out of a job. Drank himself right off Earth, too, across the galaxy to Mulciber, where Mulciber’s twin suns shone twenty hours a day and the temperature the year round was a flat seventy-seven, F. Yes, it was a tourists’ paradise, right enough, and a fine place for a man like Johnny Mantell to lose what little backbone he had left, and live a dreamy, day-to-day existence, sustaining himself with neither effort nor responsibility.

And he’d been here for seven years. A blankness in time. . . .

It was early morning. The two lemon-yellow suns were up there in the chocolate sky, and little heat-devils danced over the roasting sand. Across the few yards of white sandy beach, the calm sea stretched out to the blank horizon. The tourists from Earth and the other rich worlds of the galaxy were splashing around in the wonderful water, down in the bathing area where the mud-sharks and bloater-toads and other native life forms had all been wiped out. They were diving and swimming and splashing each other with cascades of sparkling water. Some of them had nullgravs to help them float, and some paddled little boats.

Mantell had wandered into the casino bearing lus stock in trade: sea shells, pearls, other little gewgaws and gimcracks that he peddled to the wealthy tourists who frequented Mulciber’s fashionable North Coast. He hadn’t been in the casino more than two minutes when someone pointed at him and bellowed, “There’s the man! Come here, you! Right away!”

Mantell stared blankly. The rule on Mulciber was that you didn’t raise your voice much if you were a beachcomber; you minded your business and peddled your wares, and you were tolerated. You couldn’t hang around the tourists if you made a nuisance of yourself, and Mantell had tried not to do that.

Читать дальше