The Oasans didn’t need Peter to tell them who they were. They bore their individuality with modest self-confidence, neither celebrating nor defending the eccentricities and flaws that distinguished them from others of their kind. They were like the most Buddhist-y Buddhists imaginable — which made their hunger for the Christian religion all the more miraculous.

‘You’re aware, aren’t you,’ he’d said to Jesus Lover One a while back, ‘that some of my people believe in different religions from the Christian one?’

‘We have heard,’ Lover One replied.

‘Would you like me to tell you something about those religions?’

It seemed the decent thing to offer. Lover One did the fidgety thing with the sleeves of his robe that he always did when he wanted a conversation to go no further.

‘We will have no other God than God our สีaviour. In Him alone we have hope of Life.’

It was what any Christian pastor might yearn to hear from a new convert, yet hearing it stated so baldly, so calmly, was a bit unsettling. Ministering to the Oasans was a joy, but Peter couldn’t help thinking that it was too easy.

Or was it? Why shouldn’t it be easy? When the window of the soul was clear, not smeared and tarnished with the accumulated muck of deviousness and egomania and self-loathing, there was nothing to stop the light from shining straight in. Yes, maybe that was it. Or maybe the Oasans were just too naïve, too impressionable, and it was his responsibility to give their faith some intellectual rigour. He hadn’t worked it out yet. He was still praying on it.

Then there were the ones who weren’t Jesus Lovers, the ones whose names he couldn’t even pronounce. What was he to do about them? They were no less precious in the eyes of God, and no doubt had needs and sorrows every bit as serious as anyone else’s. He should be reaching out to them, but they ignored him. Not aggressively; they just behaved as if he wasn’t there. No, that wasn’t quite right; they acknowledged his presence as one might respect a fragile obstacle — a plant that mustn’t be stepped on, a chair that mustn’t be knocked over — but they had nothing to say to him. Because, of course, they literally had nothing to say to him, nor he to them.

Determined to do more than just preach to the converted, Peter strove to get to know these strangers, noting the nuances of their gestures, the way they related to each other, the roles they seemed to play in the community. Which, in a community as egalitarian as the Oasans’, was not easy. There were days when he felt that the best he’d ever achieve with them was a sort of animal tolerance: the kind of relationship that an occasional visitor develops with a cat which, after a while, no longer hisses and hides.

Altogether there were about a dozen non-Christians he recognised on sight and whose mannerisms he felt he was getting a grip on. As for the Jesus Lovers, he knew them all. He kept notes on them, indecipherable notes scrawled sometimes in the dark, smudged with sweat and humidity, qualified with question marks in the margins. It didn’t matter. The real, practical knowledge was intuitive, stored in what he liked to think of as the Oasan side of his brain.

He still had no clear idea how many people lived in C-2. The houses had many rooms, like beehives, and he couldn’t guess how many of them were inhabited. Which meant he also couldn’t estimate how tiny, or not so tiny, the proportion of Christians was. Maybe one per cent. Maybe a hundredth of one per cent. He just didn’t know.

Still, even a hundred Christians was an amazing achievement in a place like this, more than enough to accomplish great things. The church was coming ahead. The building, that is. It had a roof now, sensibly sloped, watertight and utilitarian. His polite requests for a spire had been deflected (‘we do all other thing, pleaสีe, before’); he sensed that they would deflect it for ever.

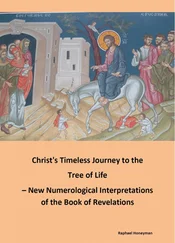

As a compensation, the Oasans had promised to decorate the ceiling. Kurtzberg had once shown them a photograph of a place they called, almost unintelligibly, the สีiสีรี่ine ฐapel. Inspired by the handiwork of Michelangelo, the Oasans were keen to create something similar, except they suggested that all the incidents should be from the life of Jesus rather than from the Old Testament. Peter was all for it. Apart from giving the church some much-needed colour, it would give him an insight into the unique nature of these people’s perception.

Lover Five, as always, was quickest off the mark, showing him her sketch of the scene she proposed to paint. It was the one outside Jesus’s tomb, where Salome and the two Marys find the stone rolled away. Evidently, this story was already familiar to her. Peter couldn’t guess which of the four gospel accounts Kurtzberg had used, whether it was Luke’s ‘two men in dazzling raiment’ story, Matthew’s angel descending from Heaven with earthquake accompaniment, Mark’s lone young man sitting on a rock, or John’s pair of angels inside the tomb. Whichever it was, Lover Five had rejected these characters and replaced them with the risen Christ. Her mourners, daintily proportioned and clad in hooded robes like herself, confronted a scarecrow-thin figure wearing a loincloth. This Jesus stood erect with arms spread wide, an eye-shaped hole in each palm of His starfish-shaped hands. Above His neck, where His head should be, Lover Five had left a blank space surrounded by a porcupine profusion of lines, to indicate radiance from an incandescent light source. On the ground between Him and the women lay a bagel-like object which Peter realised after a minute must be the discarded crown of thorns.

‘No longer dead,’ Lover Five explained, or maybe that was the title of her drawing.

Lover Five may have been first with her sketch, but she was not the first to get a painting mounted on the church ceiling. That distinction belonged to Jesus Lover Sixty-Three, an extremely shy individual who communicated mainly in gestures, even among his (her?) own people. The Oasans were scrupulous in their respect for others, and gossip was not their style, but Peter gradually got the message that Lover Sixty-Three was disfigured or malformed in some way. Nothing specific was said, only a general sense that Lover Sixty-Three was a pathetic character, soldiering on as though he was normal when everyone could see he wasn’t. Peter tried his best, without staring, to see what the problem might be. He noted that the flesh of Lover Sixty-Three’s face appeared less raw, less glistening, than other people’s. It looked as if it had been dusted with talc, or briefly cooked, like fresh chicken whose pinkness fades to white after a few seconds in boiling water. In Peter’s eyes, this made him, if anything, a little easier to behold. But to his neighbours, it was evidence of a pitiable disability.

Whatever Lover Sixty-Three’s handicap was, it didn’t affect his artistic skill. His painted panel, already affixed to the church ceiling directly above the pulpit, was the sole finished contribution so far, and any subsequent offerings would have to be impressive indeed to equal its quality. It glowed like a stained-glass skylight, and had an uncanny ability to remain visible even when the sun was on the wane and the church’s interior grew dim, as though the pigments were luminescent in their own right. It combined bold Expressionist colours with the intricate, exquisitely balanced composition of a medieval altarpiece. The figures were approximately half life-sized, crowded onto a rectangle of velvety cloth that was bigger than Jesus Lover Sixty-Three.

His choice of Biblical scene was Thomas the Doubter’s meeting with his fellow disciples when they tell him they’ve seen Jesus. A most unusual subject to tackle: Peter was almost certain that no Christian painter had ever attempted it before. Compared to the more sensational finger-in-the-wound encounter with the resurrected Christ, this earlier episode was devoid of visual drama: an ordinary man in an ordinary room voices his scepticism about what a bunch of other ordinary men have just told him. But in Lover Sixty-Three’s conception, it was spectacular. The disciples’ robes — all in different colours, of course — were scorched with tiny black crucifixes, as though a barrage of laser beams from the radiant Christ had sizzled brands onto their clothing. Speech bubbles issued from their slitty mouths, like trails of vapour. Inside each bubble was a pair of disembodied hands, in the same starfish design as Lover Five had used. And in the centre of each starfish, the eye-shaped hole, adorned with an impasto glob of pure crimson which could either be a pupil or a drop of blood. Thomas’s robe was monochrome, unmarked, and his speech bubble was a sober brown. It contained no hands, no images of any kind, only a screed of calligraphy, incomprehensible but elegant, like Arabic.

Читать дальше