Liam turned to see who had spoken. He marveled at her control. “No one is safe, Mother Nor. And never will be until—”

Her face was like a mask in the lights of the spurting fire and the gibbous moon. Her voice sank. “If such things are done in the green wood, what shall be done in the dry…?” She threw up her hands. “What shall be done, what shall be done? What can be done? I would say, Flee, let us flee again, ready for flight or not. I would say, Let us leave this accursed land! But all the Earth is accursed, and there is no part of it to which we can go where these Devils cannot follow and torment us again.

“Always I believed that following the clear and just path of Manifest Nature, the path of charity and justice and diligent equity, would eventually see an end to suffering and punishment and flight—” Her face worked. Suddenly it became stiff and still and masklike again. Liam shifted; she put out her hand to stop him. Then, slowly, slowly, as he watched, wanting to move and be about doing things, unable to stop watching and wondering, her face changed and became certain and satisfied and vigorous once more; and yet changed greatly from her former face of days.

She said, “I see now quite clearly how it is. The Devils have over-reached themselves. They have ceased to be instruments and have begun to move of themselves instead of being moved by Nature. The results, of course, are evil, hideously evil”—her hand’s sweeping gesture indicated the things on the ground she did not look at—“but at least now they have set us free. Resistance is no longer sinful, for it is now resistance against sin itself.” She looked at Liam. “And we will have to consider, consider quickly, what form resistance can take. You will have thought of that, and as soon as the people are rallied and returned, you will tell us about that. Leadership must come from you, for I am too old.”

He shook his head. Her face fell; her hands went out to him. “Rally the people, by all means, Mother Nor. And explain your new discovery to them. But I can’t stop and wait. There is something I must do now… perhaps I should have done it before, but events…

“One thing only I must impress on you, and you must impress it on everyone else: Get as far away from the water and stay as far away from the water as you can . Do you understand?”

Faintly, she frowned. “I understand the words,” she said, nodding. “But I don’t understand the meaning which must be beneath them. Are you asking me to act on faith alone? All my life I have acted on faith, but it was never at any time only on faith, for always there was enough evidence that the ways of the faithful produced a better result than those of the unfaithful.”

He told her that he had little evidence which was able to be looked at calmly and understood. But he had some such. And he would tell her what he proposed to do and what he expected would have happened by and by as the result, and what the results of the result would inevitably be. She listened further. She looked, and she nodded. “So may it be,” she said. “I will tell them. And…” She ceased, suddenly, to be leader, became again mother. Liam understood her look, her gesture.

“No, Rickar I will not need. Let him stay here, and let him add his descriptions to your explanation.” He didn’t bother to add, Besides, he is in no condition to go off and do anything else . “Duro — get back to your fathers place and spread the same word all around there, and do your best to see that others spread it as far as can be. Tom — that goes for you, your father’s place, and you see to it that the word gets as far around the coast and all the lowlands. Have you got it? I’ll give it to you again. Listen.”

“Get as far away from the water and stay as far away from the water as you can.”

The air was as close as ever before, and, as before, it throbbed with the pulse of the engines from far inside and below. “I hoped we’d never have to come back,” Lors muttered, as they walked very quickly and very carefully down yet another of the many corridors leading off from the many caves… leading inward… leading downward.

Liam said, “Well, it’s for damned certain that we’ll never be coming back again.” He grunted, and his month moved wryly. “One way or another…” His voice died away. They moved along, heads moving cautiously from side to side.

After a time they emerged once more onto the ramp running threadwise down the inside of the great cylindrical pit. They did not peer over and down this time; it would have been a needless and useless risk. And one other thing, too, was different now from the last time — this time their route was up .

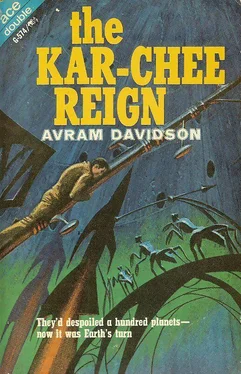

The strange lamps cast their strange light. They looked across and over: they saw no one. They quickened their steps. Upward they climbed. Upward and up. And finally they came to the first strut. They did not know what kind of metal it was or by what process it had been worked or by what process cast. It was fixed into the wall of the pit firmly and on all sides were fixed the other struts, on this level and on levels above, supporting a framework or scaffolding which seemed to go up almost forever, up to the dome roofing over the pit itself.

Lors stroked it almost reverently. “So much metal,” he said, awed.

“Up with you, or let me,” Liam said, curtly. Lors sucked in his breath with a hiss; he reached out his arms, grasped, set his right foot down, then his left. Liam followed behind him. There were odd curves and indentations in the girder, their purpose unknown, but they provided excellent hand- and foot-holds. Upward and onward they climbed, and finally reached the first of the horizontal sparrings. Here they paused to rest a short moment, and in the comparative silence they heard the sound of water trickling, and beyond that they heard something else.

A voice. A human voice.

They climbed out and along another distance to have a clearer view downward. The voice was muttering. Then it hummed something. Then it said, quite clearly, “I know you’re there!”

Lors shot out his hand, grasped Liam’s wrist. Liam pressed his lips together, shook his head.

“I know you are there. Don’t hide. Why hide? No use hiding. I know you are there. I’ll find you. I came here for that. Do you hear? Do you hear, Devils? Devils? Do you hear I’m here?” The man down below laughed, low at first; then, losing control, louder, loudly, a whooping sound which ended abruptly as though axed.

Only the thump of the engines, the dripping of the water…

“Devils, Devils, I’m going to get you for what you did to my father. He was the best father who ever lived. I didn’t deserve him. It’s my fault he’s dead. I was bad. But it was you who killed him, Devils.” The words sank lower, vanished into gibberish which then became a low and agonizing moan which froze the hairs of Lors’ neck.

Cautiously, he and Liam climbed farther out, cautiously peered down. It was, of course, Rickar. Sometimes he moved with exaggerated, almost ridiculous care, picking up each foot and lifting it high before setting it down again. Sometimes he walked sideways, like a crab, hugging the wall. Once he stumbled and Lors’s hand dug into Liam’s wrist — but Rickar did not go over the side. He landed on his knees, and, thus, still on his knees, continued on his way, crawling, creeping, crooning his insane warning. Downward. Downward. Down, down… down…

Liam sighed. He shook his head again. There was nothing they could do for Rickar this time. Nothing.

Their route continued to be upward. They climbed the girders, struts and spars like clumsy monkeys; ground-apes, returning rather gingerly to the long-forsaken trees. The sound below had either ceased or had sunk below their capacity to hear. There was once again nothing but the slow drip-drip of water. And then, gradually, another sound began to make itself known to them. A slow, infinitely slow, but infinite and endless ratcheting. It seemed to repeat its dull, one-note message over and over again forever as they climbed and climbed…

Читать дальше