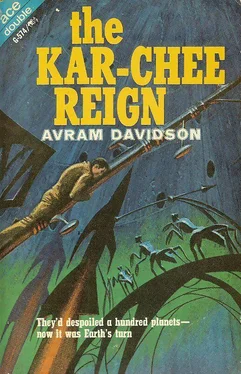

The Kar-Chee Reign

by

Avram Davidson

It was the distant future of Earth, and the mother planet of a galaxy-wide empire had been forgotten by her far-flung colonies. Forgotten, tired, old and stripped of her ores and natural fuels, Earth and the scattered bands of humans left behind were totally unprepared for the invasion of the strange, monstrous Kar-chee from the depths of the stars.

The Kar-chee had come to strip Earth of the few natural resources the planet had left — to crack the marrow of the aged planet and scavenge whatever of worth was left there. It was a massive, planet-wide operation in which continents were sunk and oceans drained, and if the tiny, insignificant humans died in these holocausts, what did that matter to the Kar-chee?

But it mattered to the humans… and, at last, they began to fight.

The big place on the old Rowan homesite had just been freshly thatched — and what a disturbance of birds, snakes, lizards, mice and spiders the removal of the previous thatch had caused — but its thick walls had stood there for generations: scarred and chipped and streaked with smoke and smeared with grease, but in all, still sturdy. The first Rowan had built well; he had not come here with his wives and children and his flocks and herds after the sinking of California, for he had had none of those. He had in fact landed with one small boat and one small dog and a determined mind and a hopeful heart, marrying a daughter of the land (that is to say, he had concluded a major treaty by the terms of which he granted use of his infinitely precious cold chisel for half a year of every year and in return was granted use for the whole of every year of an area of land for building and farming and hunting and fishing, plus a girl who had been captured almost casually from a far-off people years back and was of an age to be manned), and had put up his house according to a plan existing in his own head only — then, unprecedented; since, the standard model.

He had left behind more than a set of walls and a style in housing. His long head and long bones and wide, smiling mouth were now part of the common fabric of the people; his casual, personal turns of speech had become the way one spoke. If a problem was regarded calmly as something capable of solution instead of occasion to retreat into dreams and resigned surrender, this, too, was part of the long legacy of Rowan the first settler.

The present head of the homesite, old father and artificer, was one Ren Rowan, six generations descended from the settler on one side and seven generations removed on another; his wife’s lineage was similar, though of distant cousinship. He was all seamed and grizzled now, she — though slightly younger — only now beginning to show gray in her long hair. Her hands were deft at many tasks. It was her way to offer advice to her husband quietly and in private, it was his — usually — to take it.

“Well, we needn’t thatch this roof again for a while,” he said to her, she coming to join him on the bench more to treat him with her company than because she particularly needed rest from directing the work of feeding those who had helped with the work.

“Might think of cutting some house timbers,” she said, in her soft, slow voice. Meat sizzled and spat. There was a burst of laughter. A child stumbled and wailed, was righted and comforted with a grilled bone that filled the small mouth.

“Might,” Ren agreed. “Always might… why now?”

His eyes followed hers to where his youngest son stood in conversation with a girl on whose hip his hand rested so lightly that one might almost assume neither of them to know it was there at all. Almost; but not quite. “Mmm… That seems a flighty girl to me. I suppose she’s twitched her rump at him and now he doesn’t know whether to build a house or drag her off into the bushes… Of course, one needn’t preclude the other. Still. Flighty.”

Moma said, “Babies make good ballast. You were on the flighty side, too, recollect.”

“That was before the Devils came,” he said mildly.

“Not so long ago as that… Well. House timbers. Might think about it…”

A comfortable silence fell between them. He, his work being officially over, might have put on the loose shirt and kilt, both decoratively worked in dyed threads, which she had laid out for the purpose in their room. She, her work being officially still on, would not yet slip into the equally loose dress (only the unmarried women need endure the discomfort of tight ones), equally brightly embroidered, which hung in her corner. Both, then, were girded briefly around the waist, and wore no other clothing. The afternoon’s sun was still warm.

The moma and popa of Home Rowan looked on and about quietly and contentedly. The large, sturdy old house with its rounded ends was well- and newly-thatched; let the rains fall in due season as they surely would (forfend a drought!), it would not let by a drop. The walling palisade and gate were solid and well-set, the pens held fat stock and poultry, fields and garden were in good tilth, and the storehouses were as full as any homesite’s should be that was not niggard with its help. Neighbors, kinsmen, and even those not so allied had come to help with the work and were feeding and — depending on age — frolicking or enjoying a peaceful visit. A potbellied pupdog, descended out of the lean loins of the Settler Rowan’s lone companion on the long voyage hither, nosed along for scraps, followed by an equally potbellied grandchild. The pupdog paused, spread its legs, piddled. The child did the immediate same… Startled by the sudden laughter, he looked up, ready for tears. Seeing only Moma and Popa, he smiled proudly, and gurgled vigorously as he tottered off in pursuit of the pupdog.

It hadn’t always been a goodly scene. There had been famine, preceded by droughts; plagues of beasts and plagues of men; there was once something mightily like a little war; wild beasts had raided and attacked, and — rarely, rarely — wild men. Floods had lapped almost to the doorsills; retreating, they had left behind mud and wreckage and bloated bodies. A favored daughter had suffered of a long and painfully wasting illness before dying, and a less favored son (perhaps because of that, or for another reason none could think of) had one day walked down into the ocean and not come out. Nor had Old Ren, as he was beginning to be called, inherited the homesite peacefully. His years of enduring the usurpatous tenure of his wicked and godless uncle, Arno Half-Devil, and how he had finally wrested all away from him and sent him to die in the caves, formed the integuments of a legend which was still in formation.

And now, when the minor festivity of the thatch party ordinarily would be beginning to slow down, it received fresh life. In past the carven blue gate posts came another party of guests, their cries and gestures as they saw the new roof firmly in place already expressing a mixture of dismay and self-reproach and rueful good humor.

Old Ren said, “Jow’s people… late because they started late… started late because they didn’t think to come at all. Only coming now because Jow’s got something on his mind that came up on a sudden. Well. Got to feed them.” He rose and prepared to welcome them.

His wife said, “Won’t be enough meat. Kill or hunt?”

But he had already gestured his decision to his two younger sons, and was now waiting for Jow to bring his people and his unhappy face up to the bench to be welcomed.

Lors, Duro, four or five of young nephews and cousins to beat and help bear, and one of the just-arrived guests, uninvited, but not thereby unwelcome — trotted off, hunt-bound. Duro was still young enough to love hunting next to eating. Lors would much rather have stayed with his hand on Mia’s hip… he would much, much rather have gone with her where he could put his hand somewhere else… but his father’s expression and gesture were alike unmistakable and undeniable. Guests had to be fed, there was no ignoring it, and it was up to the popa to decide if stock were to be killed or if the huntsmen were to go out. The alternatives were equally honorable to the guests. The fields lay, for the most part, up and away from the sea. There were deer in the rainier lowlands; guanaco were to be found only in the highs, well above the fields; and now, as they came to the fork in the way, they had to decide which it was that they were to hunt.

Читать дальше