I am attracted to Trollope’s suggestion in his book The Fixed Period (1884), in which a colony near New Zealand need to deal with an ageing population. They decide that anyone over 67 must die and thus be saved from the problems of old age. I once proposed we all should have a gene which ensured painless death when we were 80 and that as everyone knew about this limited lifespan, it could be a great advantage to everyone. I have now increased that age to 85.

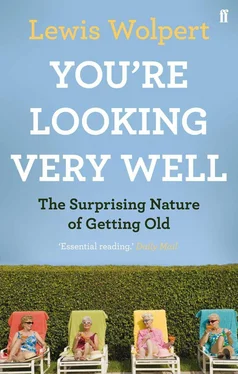

Perceived age and looking well, which are widely used by clinicians as a general indication of a patient’s health, are robust biomarkers of ageing that predict survival among those aged 70 and over, and correlate with important functional and medical conditions. So if you are told you are looking well, enjoy it for as long as you can. I find it difficult.

‘And in the end, it’s not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years’

— Abraham Lincoln

In writing this book I have learned a great deal about the serious problems that face many of the old. In addition to the problems involved in how the old are to be cared for, I hadn’t known how many of the old are so poor, and that so many need major help. I also did not know about the extent of discrimination, and why compulsory retirement is bad for so many, or how serious are the problems of of loneliness. I am nevertheless very impressed with how some of the very old cope with their age and enjoy their life. For all these problems charities like Age UK play a most helpful role and need to be supported.

I have also learned much about the biological basis of ageing, which is full of surprises, particularly the key role of evolution—we are only here to reproduce, and ageing is the result of wear and tear that is only corrected until reproduction is over. There is still much to be learned about that wear and tear in cells but progress has been impressive. There is, for example, the need to understand why germ cells do not age. Even so there are the remarkable systems in many animals whose activation can increase longevity, such as the one involving insulin signalling. Their role in human ageing is less clear. There is at present no real evidence for any way of making us immortal or significantly increasing our lifespan to, say, 150. And would we really want that unless the effects of ageing were also absent? Much more important is to find ways of reducing the effects of ageing, particularly illnesses like dementia. Politicians need to give much more attention to the problems of the old than they currently do, though the Department of Health has issued a Prevention Package for Older People. There is a strong case for there being a minister for the elderly. But for many the good news is that the government is to abolish the compulsory retirement age.

There are also major economic issues due to the ageing population of which I was unaware. For an overview I consulted Dr Richard Suzman, the director of the Behavioral and Social Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, USA. We do not have a similar institute in the UK. His views, with which I agree, provide helpful conclusions to this study:

Population ageing is a worldwide phenomenon. We are on the brink of an historic watershed and transformation. Within maybe five years or so, for the first time in history, people aged 65 and over will outnumber children under the age of five. One might expect that this will be true for the rest of history, and the same will hold for the 65-to-under-age-15 ratio. Over the next few decades, the older population is expected to grow fastest in low-income countries. Countries age in terms of population structure initially when fertility declines and then subsequently as life expectancy increases. Few expect fertility to ever rise to its previous levels, and there seems no end in sight to increases in life expectancy. Because of the high fraction of immigrants and their high fertility rate, the USA is a younger country than those in Europe, in terms of population age structure. Low-income countries are ageing before they become wealthy, and China’s one-child policy accelerated population ageing. Population ageing inevitably will present each nation with a welcome challenge—how to provide for people in old age once they have left the workforce. The alternative—that no one ever reaches the age of retirement—is less inviting.

At a societal level, the core issue is economic. The extra years of life, welcome as they are, need to be somehow financed. This can be done in a number of ways: people can work longer, consume less during their lifetime, save more for old age, consume less in old age; governments can raise taxes on those still earning to support retirees (along with children, the other dependant members of society), expand the economy through increased productivity, encourage high levels of immigration of working-age individuals, etc. The important ratio is the fraction in the labour force versus the fraction being supported out of their earnings (coupled with any private savings and pensions—which hardly exist in some nations). Balancing these needs in a way that allows for continuous economic growth and the well-being of future generations is what it is all about.

Leaving aside the issue of combining population ageing with economic growth and solvency, I think it is probably more important to maximise health expectancy than life expectancy. Old age is powerfully associated with physical and cognitive disability, especially among the ‘oldest old’, those over age 85, one of the fastest growing age groups in industrialised countries. What is important here is that the relationship between ageing and disability is plastic rather than fixed and immutable. Over a 20-year period, the prevalence of disability in the USA declined by 25 percent in the older population, though the increase in obesity may be eroding and even reversing that very positive trend. The goal of the National Institute on Aging, a component of the National Institutes of Health in the USA, is to improve both the health and wellbeing of older people. As the science of measuring subjective wellbeing improves, I would also add the maximisation of wellbeing to the mix. There are very large differences in life expectancy across both regions and social classes in the UK, with even greater internal differences within the USA (a country that since the early 1980s has lagged behind other industrial countries in life expectancy). Addressing these major inequalities should be a high priority.

In a different way, the same holds for health. The creeping obesity epidemic is likely to result in high levels of diabetes and functional disability, which will increase the demand for expensive long-term care. Efforts—or perhaps I should say, lack of effort—today could have long-term consequences for the health of future generations of elderly. Currently, for example, there are no clear-cut and experimentally confirmed ways to prevent dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The return on finding ways to prevent or delay the onset of these diseases would pay enormous dividends, both economic and in terms of wellbeing. A question I will pose, but not answer, is how governments should balance these issues against further investment in research addressing the problems. I hope that interventions that delay, prevent or remedy Alzheimer’s disease will be found within a few years. I hope that more governments in low-resource countries begin to think more seriously about their demographic futures and begin to set in place policies needed for the future. Barring disastrous new diseases, I suspect that life expectancy may increase faster than many official predictions. I fear that growing obesity will counteract some of the positive trends we have seen towards lower levels of disability in the older population. At the level of both the molecular and the whole organism, we only partially understand the process of ageing. But it is not impossible that researchers may stumble on interventions that slow down the ageing process in humans without other negative biological consequences. This would have major consequences for people and societies.

Читать дальше