Steve was back from his week at sea just in time to experience the mayhem our new kitten had caused. While he cleaned and tidied the house, I stood at the kitchen bench watching a seagull glide on the updraft from the cliff. The bird and I were at the same eye level. It swiveled the slash of its beak towards me. We exchanged glares.

Not so long ago I’d liked birds, empathized with their struggle. Around the age of eight or nine I’d found a baby thrush on the front lawn. It couldn’t fly. Our cat Sylvester was bound to get it if I didn’t do something. I scooped the ball of feathers up in my hands. It didn’t seem to mind resting its reptilian feet on my fingers. Its beak and claws were too big for its body. It was not yet a functioning bird. I had no choice but to take it inside. A shoebox was lined with cotton wool. Holes were punched in the lid with a knitting needle. The thrush took eager gulps of sugared water from an eyedropper. Certain the bird would die overnight, I closed the lid. The box chirruped. Not a call of alarm. Just a chirrup. The box sat on my dressing table all night. I dreaded what I’d find next morning. But when I scrambled out of bed and opened the lid, the bird was sitting upright. Its eyes shone black and expectant. I closed the lid and took the box outside to the front lawn. When I opened the lid the thrush hopped onto the grass. It wobbled uncertainly, then with a thrilling whirr of wings flew up onto a branch. It perched there for a while, pretending I didn’t exist. I called, but it hurtled across the valley to the pines. I thought it might fly back to thank me. Of course it never did.

The seagull peeled away, swooped down over the ferry terminal and across the harbor. Five weeks had passed since our older son, inside his white coffin, had been lowered into the hills behind Lena’s house. We’d visited the grave a couple of times. I found no comfort on the windswept summit of Makara Cemetery, with its soldier lines of plaques. The first few times we went it took a while to work out where Sam’s grave was in that mosaic of misery. Steve pointed out it was in line with the toilet block. I could almost hear Sam laughing about that. He’d always had a lavatory sense of humor. In typical incongruity he’d been buried between two people who’d lived well into their eighties. Kneeling above him, my tears irrigating the grass, I searched for something of his essence. There was nothing of him in the gnarled bushes bent permanently against the wind. Clouds wrapped themselves in improbable shapes. Sheep bleated. Sam didn’t belong in that empty place.

I felt like an actor wearing someone else’s clothes. On the outside we resembled the same people we’d been a month or so earlier. I drove the same car, went to the same supermarket, but my internal organs felt like they’d been rearranged and scrubbed with steel wool. Shock, probably. I no longer trusted the goodness of being alive. Hatred and fury flared easily. I was angry at the people who lay alongside Sam. They had no right to live so long.

Even though the new school year had started we’d decided to keep Rob home for a couple of weeks. He hardly ever mentioned Sam but he still wore the Superman watch every day. Maybe he thought the action figure on his wrist was a hotline to his big brother. Rob needed a superhero more than any boy I could think of. If only Superman could jump through his bedroom window with Sam laughing in his arms.

I began to wonder if the point of superheroes isn’t so much the extraordinary feats they perform as the fact they have other lives as uncool males struggling for acceptance. Most boys relate to Clark Kent, geeky and rejected by the woman he loves. Like Clark Kent, every boy has an inner hero. His only hope of knowing a real live Superman is to become one, a goal that sets most young men up for disappointment. As they grow older the search for Superman continues. Sports heroes, rock stars, billionaires. Yet the real hero isn’t so far away. He lies within.

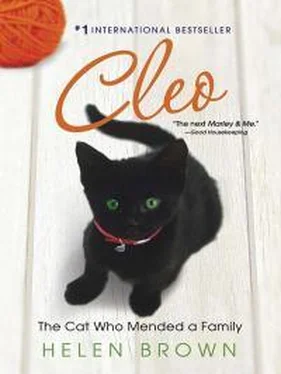

Reluctant as I was to admit it, I was getting help from Cleo. She seemed to know when I was bottoming out, whatever time of day or night it was. A paw would slide down the crack of a door, she’d leap on our bed or sit nearby, not demanding anything. Purring patiently, she’d simply wait until I surfaced.

Even her destructive behavior seemed to have purpose. It dragged us into dealing with the here and now. During the few moments I was yelling at her about curtain cords or toppled photo frames, I wasn’t eating my insides out over Sam. Infuriating, impish and bursting with affection, Cleo pulsed with exuberance. From the point of her tail to the tips of her whiskers she was one hundred percent alive. There was more Sam in her than there was under the whistling skies of Makara.

But Steve didn’t seem to see it that way. Even though I’d explained how Sam had picked her out, I had the feeling Steve associated the kitten with the life we’d had before Sam died, not this surreal existence we were trying to eke out now. Adopting a pet without his consent was hardly a functional family thing to do. Besides, he came from a long line of dog people.

Steve unpacked his seabag under Cleo’s watchful gaze. She appeared to be making an inventory of his clothes, and which might be portable. His eyes slid sideways at her. I could tell he was thinking only one word. Mess.

One of the many differences in our personalities was attitude to mess. I was, and still am, comfortable with quite a lot of disorder. Amazingly creative ideas can spring from piles of old paper and clothes you forgot you ever had. At least, that’s what I tell myself when I can’t be bothered sifting through them, which is almost always.

Steve, on the other hand, could have been mistaken for a graduate from the Zen school of the obsessively tidy. As a teenage bride, I’d strived to satisfy his craving for immaculate surroundings. Whenever he was due home from a week at sea, I’d rush around the house dusting skirting boards, straightening curtains and arranging rug tassels in parallel lines. I was a slow learner. It took years to realize that no matter how perfect I thought the house looked it made no difference to Steve’s perception. Oblivious to my efforts, he moved like a robot through the same routine every time he arrived home from sea: unleash vacuum cleaner, wipe countertops, even if I’d cleaned them half an hour earlier, and unpack seabag. Vacuuming had been out of the question today, due to the saturated shag pile. He had to content himself with picking up socks and supermarket bags.

Just as I launched into a spiel about how much Rob adored the kitten, Cleo dived into Steve’s bag and emerged with the toe of a black sock between her teeth. Scurrying away, she tossed it above her head and jumped in the air. She caught it between her front paws with panache, before rocketing away full tilt, the sock trailing between her legs. One of her back legs stepped on it, bringing her to such a sudden halt she somersaulted through the air and landed on her back. I sucked a breath. The poor creature had surely damaged her spine. We’d have to take her to the vet’s. She’d writhe in agony. There’d be no cure. Unperturbed, Cleo wriggled to her feet, picked up the sock again and sprinted away.

Unimpressed, Steve trudged out of the room in search of his sock. It generally took us two days to adjust to Steve’s routine after he’d been away. With the additional tension of an unwelcome kitten, domestic harmony was more problematic.

I’d read somewhere that seventy-five percent of marriages fail after the death of a child. I wasn’t prepared to buy into that. Defying statistics was one of my specialities. But I was beginning to understand why so many relationships crumble.

Steve’s pain was no less than mine, but it was different, more internal. I grieved in wild expressionist brushstrokes, sobbing, wailing, accusing, wanting to be held. His sorrow was more orderly and restrained. Words, when he said them, were as carefully considered as dewdrops on an orange in a Dutch master’s still life.

Читать дальше