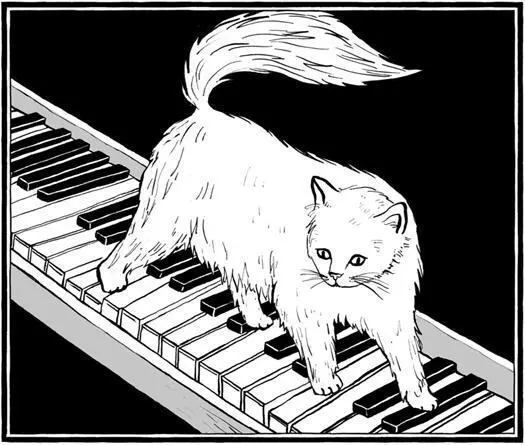

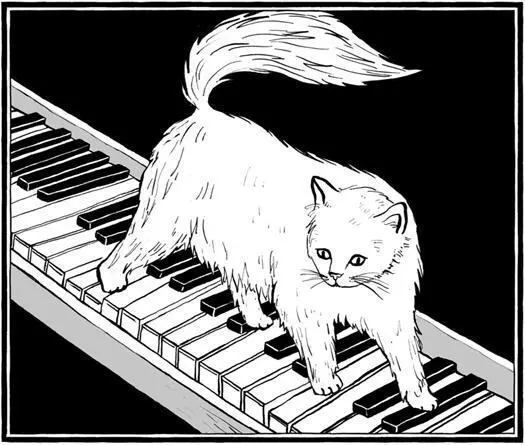

According to legend, the maestro owned a cat named Pulcinella, who enjoyed walking up and down the keyboard of his harpsichord. Usually this produced only random, meaningless noise. But during one of these “improvisation sessions,” the feline plinked out an unusual, though quite catchy, series of notes. Scarlatti grabbed a pad and wrote down the short phrase. Inspired, he composed an entire fugue around it.

The piece became an instant success, and it remains so today. During the 1840s, the great pianist Franz Liszt added the work to his repertoire—it became a regular part of his performances. By that time a major oversight on Scarlatti’s part had been rectified. At the time he wrote it, the idea of somehow noting the origin of the piece in the title simply didn’t occur to him. But by the early nineteenth century the brilliant bit of feline-inspired music had become universally known as the Cat’s Fugue.

CALVIN

THE CAT WHO INSPIRED TWO AUTHORS

It is the rarest of literary cats who serves as the muse of not one but two writers. Such was the case for a fluffy Maltese named Calvin. He entered the world of letters in the mid-nineteenth century, when he wandered “out of the great unknown” into the household of Harriet Beecher Stowe. “It was as if he had inquired at the door if this was the residence of the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin , and, upon being assured that it was, had decided to dwell there,” remarked family friend Charles Dudley Warner. Calvin immediately made himself at home. He hovered nearby as Stowe wrote, sometimes even perching on her shoulders. All were impressed not only by the feline’s self-confidence, but by his intelligence. “He is a reasonable cat and understands pretty much everything except binomial theorem,” said Warner.

He was in a unique position to know. When Stowe decamped from her New England home to Florida, custody of Calvin was awarded to him. The cat prowled his Connecticut estate for eight years. “He would sit quietly in my study for hours, then, moved by a delicate affection, come and pull at my sleeve until he could touch my face with his nose, and then go away contented,” Warner wrote. He could also open doors on his own and open register vents when he felt cold. According to his owner, Calvin seemed equal to almost any challenge, save for one: “He could do almost any thing but speak, and you would declare sometimes that you could see a pathetic longing to do that in his intelligent face.”

Calvin became such a part of the family that, when the feline finally passed away, he received a long, loving eulogy in the author’s bestselling collection of 1871 essays, My Summer in a Garden . The elegy, called Calvin (A Study of Character) , became nationally famous. “I have set down nothing concerning him but the literal truth,” Warner wrote. “He was always a mystery. I did not know whence he came. I do not know whither he has gone. I would not weave one spray of falsehood in the wreath I lay upon his grave.”

The pint-sized literary lion who loved the world of letters had now become a part of it forever.

DINAH

THE SECOND-MOST-FAMOUS CAT IN ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Ask the typical reader to name the feline star of the Lewis Carroll books Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass , and he or she will likely mention the Cheshire Cat. But another cat plays an important role in the two works. It’s a cat who, like so many characters in the books, was based in reality.

Carroll, whose real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, first spun the tale during a lazy afternoon boat trip down the Thames River with a friend, Robinson Duckworth, and three little girls of whom he was particularly fond: Lorina, Alice, and Edity Liddell. The three enjoyed the story so much that Alice, the tale’s namesake, asked Dodgson to write it down. He did, showed the draft to friends, and was encouraged to find a publisher. The first of the two books, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland , was published on July 4, 1865. It became an immediate sensation and has remained in print ever since.

For a tale of fantasy, the book includes a great many thinly disguised real people. The protagonist is, of course, Alice Liddell. Robinson Duckworth becomes the Duck, and Carroll himself becomes the Dodo (perhaps because he stuttered, which caused his real last name to often come out as Do-Do-Dodgson). As for pets, the book’s Alice talks repeatedly about Dinah, Alice Liddell’s real tortoiseshell tabby. Interestingly, the references form one of the dark, rather sadistic veins that flow through the text.

Whenever poor Dinah comes up in conversation, it’s always in the context of thoughtless cruelty. For instance, early in Wonderland , Alice mentions how her pet is “such a capital one for catching mice,” apparently forgetting that she’s conversing with a talking mouse at the time. And later, in Looking Glass , she makes the same sort of faux pas when addressing a group of birds. “Dinah’s our cat,” she says. “And she’s such a capital one for catching mice you can’t think! And oh, I wish you could see her after the birds! Why, she’ll eat a little bird as soon as look at it!” No wonder Alice got into so much trouble in Wonderland.

FOSS

THE CAT WHO WAS ALMOST TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE

The cats of great artists and writers often find themselves immortalized in their masters’ works. But in the strange case of nineteenth-century British artist and writer Edward Lear, a bit of poetic whimsy seems to have found its way into the real world.

The bearded, bespectacled eccentric gained fame as a painter of animals and landscapes. But he also published several books of children’s nonsense poems that made him internationally famous. Many, including The Owl and the Pussycat , are still read to toddlers today.

Lear illustrated his poems with lighthearted cartoons. One of his favorite subjects was a striped tomcat named Foss, who he acquired in 1872. Lear’s devotion to his pet is quite amazing, considering that Foss was by all accounts a most unattractive subject. He was fat, with a bobbed tail reportedly cut off by a superstitious servant who believed it would stop him from roaming. Yet there’s no end to the pictures Lear drew of himself and his rotund friend on adventures. No photos exist of the famous feline. When Lear tried to take one, the big orange cat jumped out of his master’s arms just before the shutter clicked.

Lear loved Foss so much that, when the artist built a new home, he made it look exactly like his old one, so as not to upset the cat. And when Foss passed away in 1887, he was buried in his master’s garden under a large memorial stone. Lear himself died only two months later.

Today pictures of Foss can still be seen in collections of Lear’s nonsense poems. But there’s something mysterious about them. The real Foss didn’t enter the artist’s life until 1872. Yet years earlier he regularly produced drawings of a similar fat, striped, stub-tailed cat. And for some reason, Lear was convinced that Foss lived a near-impossible thirty-one years—so much so that he had that figure carved on his friend’s tombstone. Perhaps he saw the real Foss as the incarnation of the imaginary cat he’d carried in his mind’s eye for decades. “Edward adored Foss, and it was mutual, but the Foss we know belongs more to the world of nonsense stories than he does to the real world,” says Lear biographer Peter Levi. Maybe he always did.

Читать дальше