MICETTO: A large tabby cat born in the Vatican who became the favored pet of Pope Leo XII. The pope allegedly held audiences while Micetto hid in his robes .

WHITE HEATHER: A fat Angora who was Queen Victoria’s favorite cat. The cat managed to outlive the famously long-lived queen and became the property of her son and successor, King Edward VII .

Arts and Literature

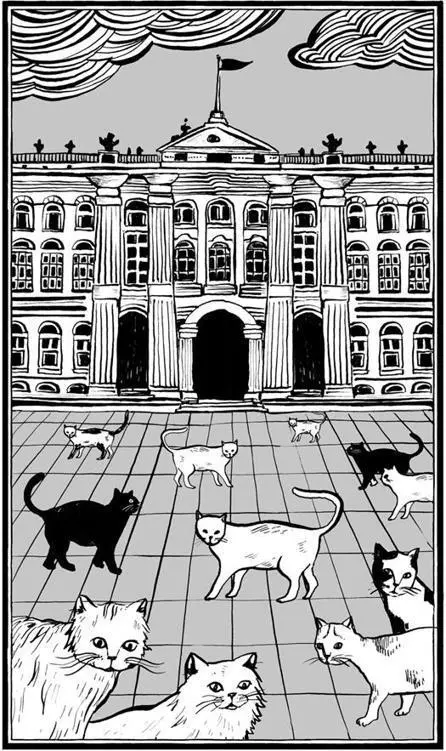

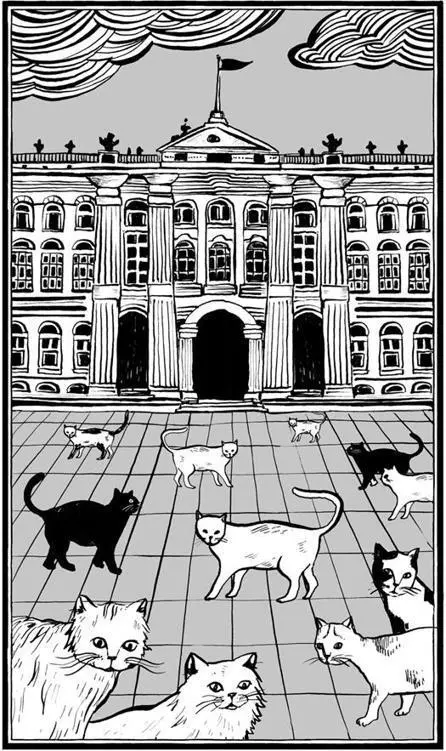

THE HERMITAGE GUARDS

THE CATS WHO WATCH OVER RUSSIA’S GREATEST MUSEUM

Cats have always been great friends of libraries and museums. Because mice and rats will chew up an important old manuscript or a priceless painting just as readily as they would an ear of corn, numerous cultural centers have employed feline assassins to keep vermin damage to a minimum. But few such groups are as ancient, as numerous, or of such regal ancestry as the feline army defending the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Today a force of roughly fifty cats watches over the sprawling complex, just as they have for more than two and a half centuries. Their work began back in the days when the Hermitage was still a palace for the czars. In 1745 Peter the Great’s daughter, Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, decided she’d had enough of the rodents in the building. She issued a royal proclamation decreeing the roundup of “better cats, the largest ones, able to catch mice.” They were to be dispatched to the court, accompanied by someone who could look after them.

The first contingent of felines arrived shortly thereafter. They must have done their work well, because they remained through the reign of every czar. They also survived the communist revolution intact, though the descendants of the original band were decimated during World War II. Saint Petersburg (then called Leningrad) was blockaded for months by German troops. Food became very scarce, and many of the Hermitage cats became entrées.

After the war, their numbers were replenished. While the cats the czars kept were said to be Persians, today’s collection is a somewhat motley assortment of former strays domiciled in the building’s basement. Donations by employees and proceeds from an annual sale of paintings made by the children of Hermitage workers are used to pay for the cats’ medical care, shelter, and food to supplement whatever they catch on their own.

Though the felines regularly patrol outdoors, they’re no longer allowed in the galleries and exhibit halls. On rare occasions, however, some do find their way in. But since they usually trigger the museum’s elaborate electronic security system in the process, they’re promptly escorted right back out.

SELIMA

THE CAT WHO DIED FOR ART’S SAKE

Many cats enjoy posthumous honors, but few have been commemorated so artfully, or in such varied mediums, as Selima, the companion of eighteenth-century British author, politician, and aristocrat Horace Walpole, fourth Earl of Orford. Perhaps she received so much attention because she died so colorfully. While attempting to reach some goldfish in a porcelain vase, Selima fell in and drowned.

Walpole was bereft. He had an inscription about the cat carved on the offending vase (which can still be seen at his mansion, Strawberry Fields), and asked a poet friend, Thomas Gray, to author an epitaph. Gray went him one better, composing Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat . It advises the reader against striving blindly for unworthy goals, and it ends with the line that has made it immortal: “Not all that tempts your wand’ring eyes / And heedless hearts is lawful prize. / Nor all that glitters, gold.”

As if this weren’t enough of a monument, in 1776 the artist Stephen Elmer executed a painting called Horace Walpole’s Favourite Cat , showing Selima perched precariously over the goldfish bowl. Nearby sits a book, opened to Gray’s Ode .

BEERBOHM

THE CAT WHO UPSTAGED BRITAIN’S FINEST THESPIANS

For centuries no self-respecting English theater—at least, none that wished to be free of vermin—could do without a cat. But besides hunting mice, these felines came to serve other functions. Actors considered them good luck charms, and their calming presence cured many a bout of stage fright. They grew so useful that even the most egotistical performers overlooked the fact that the cats occasionally wandered onstage during productions, upstaging their human associates.

No modern theater cat served as ably, as famously, or as long as Beerbohm, who handled vermin suppression duties at the Gielgud Theatre (formerly the Globe) in London’s West End from the 1970s to the early 1990s. The regal-looking tabby often picked certain actors to fawn over, and he wandered onto the boards at least once during the run of every show. Named after British stage veteran Herbert Beerbohm Tree, he worked in show business for twenty years before retiring to Kent to live with the company’s carpenter. He died in March 1995—a sad passing that was honored with a front-page obituary in the theater newspaper The Stage . His portrait still hangs in the Gielgud.

HODGE

THE CAT WHO HELPED WRITE A DICTIONARY

Many a famous poet or novelist has written under the languid gaze of a feline. But few such four-legged muses can match the grit and staying power of a black cat named Hodge. He provided companionship to lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) as he single-handedly composed the first truly authoritative dictionary of the English language.

Johnson gave eleven years to the work, churning out definition after definition at his home at 17 Gough Square in London. As the great lexicographer labored at his desk, Hodge was often at his elbow, amusing and diverting his owner from what must have been an unimaginable grind. The project was finally completed in 1775. It won universal acclaim, became the literary world’s reference of choice for more than a century, and earned its author the nickname “Dictionary Johnson.”

However, the world knows about Hodge (and his master) not because of the dictionary, but because of a young Scotsman named James Boswell. Boswell befriended Johnson in 1763 and spent the next few decades following him around, scribbling down the sage’s comments and making no secret of his desire to write the great man’s biography. In 1799, he duly produced The Life of Samuel Johnson , considered the first truly well-rounded, sympathetic, modern biography. It made Johnson, who might have merited no more than a footnote in the history books, into an immortal literary character.

Boswell also turned Hodge into a famous literary cat, despite being pathologically afraid of him. “I never shall forget the indulgence with which he treated Hodge, his cat: for whom he himself used to go out and buy oysters, lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature,” Boswell wrote in The Life of Johnson . “I am, unluckily, one of those who have an antipathy to a cat, so that I am uneasy when in the room with one; and I own, I frequently suffered a good deal from the presence of this same Hodge. I recollect him one day scrambling up Dr. Johnson’s breast, apparently with much satisfaction, while my friend smiling and half-whistling, rubbed down his back, and pulled him by the tail; and when I observed he was a fine cat, saying, ‘Why yes, Sir, but I have had cats whom I liked better than this’; and then as if perceiving Hodge to be out of countenance, adding, ‘but he is a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed.’ ”

Читать дальше