I have also altered identifying characteristics of some of the other Russians featured in this story, again to minimise the possibility of retribution being wrought. The scene in which Phil smuggles the footage out of prison was shifted from the place it actually happened, to protect ‘Mona’ from serious criminal charges (it’s best she doesn’t find herself in the women’s section of SIZO-1).

I wanted to give a more realistic portrayal of the incarcerated women than the one offered by some media outlets during their time in jail. In many newspapers there was an assumption that the women would be coping less well with their ordeal than the men. Alex became keenly aware of the discrepancy when she googled her name at the Peterville hotel. Many of the photographs were of her crying in the cage at her first appeal in Murmansk. That moment appeared to define her, and it is something for which Greenpeace – myself included – bear some responsibility. In some countries the organisation made Alex the face of the campaign and used the image of her at the appeal hearing on advertisements and leaflets. When, after her release, she saw how her tears had been used, she tried but failed to hide her disappointment. I tried but failed to hide my culpability. I had authorised those adverts.

‘These stereotypes piss me off,’ she told me. ‘I don’t like the way everyone portrays the women compared to the men. When I needed to cry, I cried. When I needed to scream, I screamed. Being true to yourself and your emotions isn’t a weakness, it’s not something I’m ashamed of. But the way the articles are written, people were more worried about me because I cried, or they were more worried about the women because we’re women.’

In reality the women were as strong – if not stronger – than the men. Often the younger activists coped better than the older ones, in part no doubt because they were less likely to have long-term partners or children back home. In St Petersburg after their release the women were a source of constant, unbridled, positive energy. I remember one night standing in the Helsinki bar, drinking shots of vodka with Kieron, watching Alex, Camila, Sini and Faiza dragging everyone – Russian strangers included – off their chairs and onto the dancefloor. A Michael Jackson track had just come on, one that used to be played on Bridge TV back at SIZO-1, and they were recreating the dance moves they made in their cells. And I remember saying to Kieron, ‘When I grow up I want to be Sini Saarela.’

Sometime later I asked Kieron how he managed to survive each night back in that isolation jail in the Russian Arctic.

‘You don’t really,’ he said. ‘You just tell yourself that the fifteen years might happen. You tell yourself to get used to that sick feeling because eventually that might be reality. I wrote a letter to Nancy’ – his girlfriend, later his wife – ‘and I said to her, look, if this goes really bad there’s no way I expect you to wait for me. My big fear was missing out on having a family because being forty-four in fifteen years I would’ve lost the person I wanted to marry, lost my career, the people I love, and every semblance of joy and success I’ve had would be totally obliterated by this fifteen years of darkness. I actually remember thinking I won’t make it fifteen years. I honestly didn’t think I’d get that far. Would I top myself? Yeah, I think I probably would. But you have to keep hoping.’

As hard as it is to imagine, many of the prisoners’ families had it just as bad, and I regret not being able to tell more of this story from their perspective. I interviewed some of them but the narrative became increasingly cluttered, so instead I sought to have Pavel Litvinov represent them in this account. Despite his remarkable history, he was, in late 2013, just one more terrified parent. In the absence of more of their experiences, this book is dedicated to the families of the Arctic 30.

It was an incredible honour for me to interview Pavel. I knew of his iconic protest in Red Square, having long ago read Lenin’s Tomb – David Remnick’s remarkable book about the fall of the Soviet Union, in which he features prominently. But despite being moved by his courage and inspired by his activism, I didn’t realise until September 2013 that he is Dima’s father. Only when he brought his considerable energy to the campaign to free his son did I become aware that this was the same Pavel Litvinov.

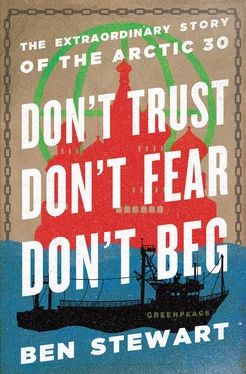

I sought to raise an important question in the book, but it’s not one I tried myself to answer. Was Greenpeace naïve to scale the side of a Russian Arctic oil platform and expect to sail away unmolested by Putin’s judicial machine? I have heard a dozen different answers. One senior colleague told me he thought everything had gone exactly according to plan, that creative disruption brings about change, that if we’re serious about challenging the fossil fuel behemoths then people are going to have to go to jail. Equally I have heard many people at Greenpeace claim that nobody could have predicted what would happen. After all, a year earlier the crew of the Arctic Sunrise had launched an almost identical protest and the FSB had done nothing. And others – including some of the thirty – say yes, it was naïve of Greenpeace to have sailed for the Prirazlomnaya and not thought jail for its activists was the likely outcome.

In a sense the question is subjective. There is perhaps no right or wrong answer. A more relevant question might be, ‘Was it worth it?’ And that is for nobody to answer but the thirty themselves. In interviews in St Petersburg most of them said yes, it was. But some would disagree, not least because of the impact on their families, and who could blame them?

Another question often asked is, ‘Did it change anything?’ I would say it did. Securing action on climate change is hard. We are all implicated in the fossil fuel economy, and most political and corporate leaders are yet to determine that it’s in their interests to truly roll back dependence on oil, coal and gas. We are caught in the same paradox as Dima was in his cell at SIZO-1 when he started smoking then realised he’d gain nothing by giving up. It only took one prisoner to light up to make it pointless for the others to quit, because they all shared the same air. And it’s a bit like that with climate change. Those with the power to effect change – prime ministers, presidents and CEOs – think there’s nothing in it for them to act alone, that it’s only worthwhile quitting fossil fuels when everybody else does, because we all share the same atmosphere.

The campaign to save the Arctic is not yet won. In fact it’s barely begun, and we don’t have much time left. But direct action – the manifestation of resistance, the ignition of controversy from apathy – speeds up the national and global conversation, it short-circuits ponderous political cultures and forces uncomfortable issues onto the agenda. It is asymmetric campaigning, a leveller, a way for the weak to take on and beat the strong, to make governments and corporations act against their immediate interests. To break that paradox.

The night he left Russia for home, I sat with Dima in the hotel bar as he wrote his statement for the press. With my laptop balanced on his knees he bashed away at the keyboard, then he passed me the computer and said, ‘Release that.’ He got up and walked towards the door, his pink bag slung over his shoulder, his wife’s hand in his, and I looked down at what he’d written.

I’ve never regretted what I did, not once, not in prison and definitely not now. Sometimes you just have to stand up and ask to be counted, and that’s what we did in the Arctic. They didn’t throw us in jail for what we did, they locked us up because of what we stood for. The Arctic oil companies are scared of dissent, and they should be. They may have celebrated when our ship was seized, but our imprisonment has been a disaster for them. The movement to save the Arctic is marching now. Our freedom is the start of something, not the end. This is only the beginning.

Читать дальше