The police take a moment to notice what’s happening, but the cops on the jetty don’t move and the boats in the water are too far away to reach them. Sini turns her head and looks back and sees Phil swimming behind her. And the other climbers are launching themselves into the sea as well. A moment later they’re all in the water, kicking hard, six of them, all weighed down with kit but getting closer. Then Sini reaches out and grabs the bottom rung of the ladder and hauls herself up.

Faiza is watching from the deck of the Argus, but the huge hull of the Mikhail Ulyanov is blocking her view and she can’t see what’s happening. Then her phone rings. It’s the team on the jetty. They tell her they’re hanging from the ladder, stopping that tanker from unloading its cargo of Arctic oil.

‘For me it was very logical,’ Sini remembers. ‘The issue hadn’t changed, it was the same fucking dirty oil, why wouldn’t I protest against it? They’d started drilling and this was the first oil coming from that platform. My motivations hadn’t changed in jail, if anything they’d become stronger. So in the end, whether or not I’d jump, I guess it wasn’t really a question.’

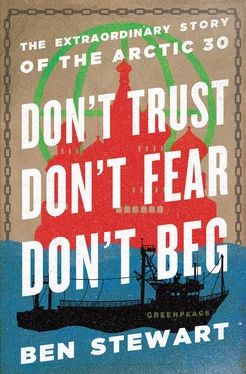

In September 2013 I took a phone call from Mads Christensen, at the end of which he asked me to lead the international media team pushing for the release of the Arctic 30.

‘We need to make them famous,’ he said. Then he hung up.

I lowered the phone and wondered if I’d actually agreed to take the job. I didn’t say I wouldn’t do it, so I guessed that meant I was doing it. Suffering as I do from acute imposter syndrome, I thought momentarily about calling him back and politely declining the offer, but I knew half the people in jail and some of them were good friends. I’d climbed power station chimneys with them and broken into polluting factories at their side. I’d sailed to Greenland with Iain Rogers, Colin Russell and Mannes Ubels. I was slated to join the Sunrise on its mission to the Russian Arctic, but my boss wouldn’t let me go and Alex went instead. It could have been me in that Russian prison cell.

The next three months were spent in a maelstrom of black coffee, boiled sweets and fear, as we managed a publicity operation spanning dozens of countries across the world. I neglected the people I loved and gave myself over entirely to the Room of Doom. The only times I left that place for an extended period were a strategy meeting in Copenhagen, a failed attempt to spend a weekend away with my girlfriend, and the moment the Arctic 30 were released.

After the news from Ana Paula’s hearing I sped to St Petersburg and checked into the Peterville hotel. Half an hour after Sini and Camila were freed I stood at the end of a corridor watching them bouncing on their heels and grinning wildly as they opened the door to their room. Behind them Ana Paula and Anne Mie were hugging each other. Since September those faces had stared back at us from posters on the wall of the bunker and from newspaper front pages, and now they were there, in front of me. Perhaps it was a product of the pedestal we all put them on while we were working for their release, but I remember thinking they all looked a lot shorter than I imagined they’d be.

The following evening I sat with Frank in the Peterville café, each of us nursing a beer, and he told me about that night at SIZO-1 when his cellmate yanked the U-bend from the wall and he heard the voice of Roman Dolgov broadcasting through the plumbing system. Then Frank told me more stories – about Popov, his cellmates, the guard who loved Depeche Mode – and as he spoke I jotted down notes on a napkin. I thought those stories might be the basis of an email to my colleagues around the world to whom I was sending updates from St Petersburg. Frank and then Anthony reeled off more tales, I scribbled on more napkins and stuffed them into my pockets, but eventually I stopped writing and just sat back and listened. And at some point that night I thought somebody should write a book about it all.

Back then I was still utterly consumed with the campaign to get them home and, more immediately, the job of managing the huge media interest in the men and women pouring out of jail. Dozens of journalists were travelling to St Petersburg or had already arrived. A Swiss TV crew refused to leave the hotel bar until they’d interviewed Kruso. A British newspaper reporter was stalking the corridors looking for Alex, determined to negotiate an exclusive deal.

Five weeks after they were freed, I came home with the British activists, and soon after they stepped onto the concourse at St Pancras station I slipped away, took a train home to my family for a belated Christmas and collapsed exhausted onto my bed. For two days I didn’t leave the house. But when I did surface, I pulled those napkins from various pockets and read through them again, and I thought, yes, somebody should definitely write a book about it all.

I left it a month, then started interviewing the activists, in person and on Skype. And I spoke to many of my colleagues from the hubs in Copenhagen, London, Amsterdam and Moscow. I was fortunate that a team of volunteers transcribed those interviews – more than forty hours in total (you can listen to some of them at www.donttrustdontfeardontbeg.com). I then retreated to a house in the countryside for a fortnight, carrying a three-inch pile of printed interviews and a pack of luminous magic marker pens.

My plan was to highlight the quotes that might conceivably be moulded into a narrative, but by the time I reached the end of the pile, most of the sheets were almost entirely covered in bright green, pink and yellow ink. So many stories, so many characters. It felt like there were a dozen books in there, and I was yet to find a single one of them.

Only by concentrating on four or five of the thirty – and a smaller number of the campaigners – did something digestible begin to emerge. The result is a book that fails to tell a host of remarkable stories. An entire second volume could be written about the experiences of Faiza, Kieron, Roman, Colin, Andrey, Denis, Anthony and the others.

I had a few stories myself, and in the first draft I sought to tell them. The text was littered with ‘I’, ‘we’ and ‘us’. But when I read back through the chapters, those parts – the ones told in the first person – struck a bum note, like a chord played on a badly tuned piano. This isn’t my story; it’s the story of the activists who were jailed in Russia for scaling an Arctic oil platform. Trying to relate my own experiences amid those tales from SIZO-1 felt like jumping out of the crowd at a football match and running onto the pitch dressed in a replica kit.

So I exorcised myself from this book. Nevertheless, some of the events relayed here are ones I witnessed or participated in.

That three-inch pile of paper contained some gaps of recollection and detail. Dima’s memory for conversations, especially between him and Popov, was extraordinary, but not everyone remembered so easily. Therefore I occasionally reconstructed details and dialogue before checking my efforts with the activists to ensure accuracy.

The English of some of the Russian prisoners was so limited that the articulation of a single sentence would take an age, and they often used sign language as much as the spoken word. I have tried to reflect that in the nature of their dialogue, whereas the words spoken in Russian – for example by Vitaly to Dima – are more immediate and expressive because they were said in the mother tongue.

Vitaly, I should say, is not his real name. I have changed the names and some identifying characteristics of the Russian prisoners because I was not in a position to ask their permission to recount their stories. I feared – perhaps unrealistically, but who can say? – that those still behind bars might face retribution for some of the things I report them saying and doing, not least the support they offered their Greenpeace cellmates. I would not like to make the job of Popov any easier.

Читать дальше