No. Because there it was, a ring of black rocks — not white, and far smaller than expected but exuding unmistakable Spiral Jetty —ness. Smithson warned that size is not the same as scale, that ‘size determines an object, but scale determines art.’ Fair enough, but I’d seen photographs with people — those centuries-old indicators of scale — on the Jetty , dwarfed by it. In the midst of all this sky and land the real thing was quite homely in size and scale. Unlike The Lightning Field, the Spiral Jetty looked better in photographs than it did in the rocky flesh.

We walked towards the circles of stone, could see that these circles were actually part of an unbroken spiral. This was the Spiral Jetty . We were no longer coming to the Spiral Jetty. We were at the Spiral Jetty, waiting for the uplift, the feeling of arrival — not just in the getting-there sense but in the way Lawrence had experienced it at Taos Pueblo. And it sort of happened. The weather had been quietly improving. The sky, in places, had turned from lead to zinc. Patches of blue appeared. And now, for the first time that day, the sun came out. There were shadows, light, a slow release of colour.

We clambered down to the Jetty —there was no path — through a slope of black rocks where someone had fly-tipped an exhausted mattress. The Jetty extended in a long straight spur before bending inwards. The water was plaster-coloured, slightly pink, changing colour as it was enfolded by the spiral, at its whitest in the middle of the coil.

We had hoped the Jetty would be visible. Not only was it visible — you could walk on it too. The magical coating of white crystal was largely gone, rubbed off, presumably, by people like us tramping all over it. But what’s the alternative? You can’t cordon it off like some relic in a museum, so we did our bit in helping to take off the residual shine, further restoring the Jetty to its original condition. Compared with Angkor Wat and the pyramids, the Jetty was not doing too well. It had aged at the rate of the rain-smeared concrete of the Southbank Centre or council estates done on the cheap and put up in a hurry. In less than forty years it already looked ancient. Which, actually, is the best thing about it. The Lightning Field looks perpetually sci-fi; in next to no time, the Spiral Jetty had acquired the bleak gravity and elemental aura of prehistory. It would be easy to believe that it had been built millennia ago by the people who first settled here — but why would they have settled here of all places?

The artist John Coplans wrote that entering the spiral involved walking counter-clockwise, going back in time; exiting, you go forward again. That’s true, part of the conceptual underpinning of the experience. But he forgot another, no less important, lesson of perambulatory physics, what might be called the Law of Sink Estate Directness. At Downing College, Cambridge, signs — and hundreds of years of observed convention — warn that only Fellows may walk on the grass. Rather than walk across the prairie-size quad, you have to take a frustrating detour around the edges. In less august settings any attempt at decoration or elaboration that involves lengthening people’s journey time is destined to fail. Rather than walk two sides of a square — even if it is named after Byron or Max Roach — people will cut across it diagonally, lugging orange-bagged souvenirs of their pilgrimage to Sainsbury’s cathedral, creating their own, urban version of a Richard Long. Before long — or contra Long — the grass starts to wear out and a so-called ‘desire path’ is formed. Same here. Although the stretches between the spiraling rock were underwater, the salt beds were soggy but firm. So you didn’t need to walk around the spiral, you could just step across! Why walk back in time when you can jump-cut across it in a flash? In moments you are at the end of the spiral — the dead centre of the space-time continuum, the still point of the turning world.

Near this centre earlier visitors had arranged rocks and stones so that they spelled out names in the white salt of the enclosed lake bed: missy (with a heart underneath), ida marie and estelle.

The sky continued to open up. With the sound of birds and lapping water, it was lovely in a subdued and desolate way. It felt abandoned but it was not a place of abandoned meaning. It had retained — or generated — its own dismal nodality. The answer to the obvious question — was it worth coming all this way? — might have been no, but it didn’t occur to us to ask. The Spiral Jetty was here. We were here. That was the simple truth. Could the more complex truth be that if it wasn’t so difficult to get to no one would bother coming to see it?

André Malraux famously cherished the idea of a museum without walls. In a way, places like the Spiral Jetty are jails without walls. They are always about time, about how long they can detain or hold you. I remember the governor of a U.S. prison saying, of a particularly violent inmate, that he already had way more time than he’d ever be able to do. That’s exactly how the Jetty looked — like it already had more time than it could ever do — even though, relatively speaking, it had hardly begun to put in any serious time.

In uncertain tribute, we stayed longer than we needed to, waiting for any potential increments of the experience to make themselves felt. One or the other of us kept saying, ‘Shall we go?’ and, in this way, our visit was gradually extended. Nothing happened except the slow erosion of urgency and purpose. We were often ready to leave, but every time we thought about leaving we remembered the previous time we had thought about leaving and were glad the urge had not been acted on.

And then, eventually, without a word, when the desire to leave was all but extinguished, we began walking back to the car. The air was irritable with sandflies. I almost trod on a long, grey, indifferent snake. The lone and level lake stretched far away.

Sites such as those painted by Vedder are not always mired in the sands of the past: they are still coming into existence, are continually being created, even if they cannot always be seen — as when a construction worker mixed a Boston Red Sox T-shirt into concrete that was being poured into part of the new Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, aiming to curse it.

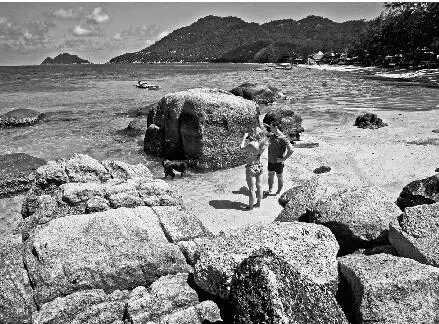

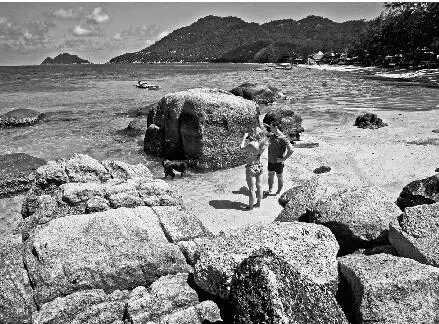

In a photograph taken by Chaiwat Subprasom in 2014, we can see the very beginning of the processes at work in the formation of one such potential site. At first glance it seems a nice if rather pointless holiday snap. More accurately, a photograph of people taking a rather pointless holiday snap. In this respect it — the snap — is exemplary, since 90 percent of the pictures now being taken are pointless. The weather is fine, the beach is nice, the water is a gentle, unthreatening turquoise, but it’s not as if the rock in the middle is covered in ancient petroglyphs or even graffiti. That leaves the dog. A nice enough doggy, to be sure, and there’s always something fun about a dog at the seaside — until it comes trotting back and leaves sand and saltwater all over your sofa. .

Except this is the beach on Koh Tao in Thailand where the bodies of two murdered British tourists had been discovered two weeks earlier. This knowledge changes everything — including our perception of the dog, who now seems to have sensed or scented something untoward. In its modest way the picture being taken by the woman in the bikini recalls Joel Sternfeld’s photographs of parking lots or street corners in On This Site: unremarkable spots transformed into photographic memorials by captions explaining that these are places where a rape, murder or abduction took place. The couple in the photograph probably offered a similar explanatory caption when they showed the picture to friends or posted it on Tumblr. Still, their picture was not anything like as interesting as this one: a photograph showing the transformation being made. It is the act — her act — of taking the picture that invests the site with meaning. Her picture might be pointless; the act of taking it is not. Quite possibly she is taking it not to make a visual record but to offer some kind of tribute, to pay her respects in the way that, had any been available, she might have left a bunch of flowers. This is often the case: people don’t take pictures in order to have a picture; they take pictures because that is what you do. Perhaps it’s better put interrogatively: what else can you do? The man provides the answer: you just stand there.

Читать дальше