Also, contrary to Beardsley’s griping, access is arranged in such a way as to maximise this experience. You leave your cars at Quemado and are taken up, in a group, at two-thirty in the afternoon. The drive takes half an hour, so you arrive at the least impressive time of the day. As we approached, a groan of disappointment swept through our party: we didn’t know exactly what we were expecting but we expected more . More what? More something. And then, gradually, you get it. You realize that this is not a piece of art to be seen but — the point bears repeating — an experience of space that unfolds over time.

This is one of the reasons why The Lightning Field is almost unphotographable. It is too spread out — and it takes too long. Everyone sees the same picture — the one on the cover of Robert Hughes’s American Visions —of a lightning storm dancing round the poles. That is what might be called the Lightning Field moment. Lightning may be rare in actuality, but it is right that The Lightning Field should be represented in this way. Every other attempt to reduce it to an image, a moment, sells it short.

Within the agreed limits of your visit — you’re taken up there and brought back — you can do whatever you like. Few religious sites permit such freedom of behaviour and response. You can drop acid. You can run around naked. You can drink a ton of beer and watch your woman pole-dance. You can sit on the porch reading about the Spiral Jetty. You can chant. You can chat with your friends. You can listen to music on your iPod, or you can just stand there with your hands in your pockets, shivering, wishing you’d brought gloves and a scarf. And then you have to leave.

We were picked up at eleven o’clock and driven back to Quemado. In a couple of hours the next bunch of pilgrims would be taken up there. If it hadn’t been for them — if it hadn’t been booked — we would all have stayed another night, for a week, for the whole summer.

As it was, we ate cherry pie in the El Sarape café and took some pictures to prove we’d all been here together. There’s a dusty Ping-Pong table in the otherwise deserted Dia office. Ethan and I played a couple of games before we all headed out of town.

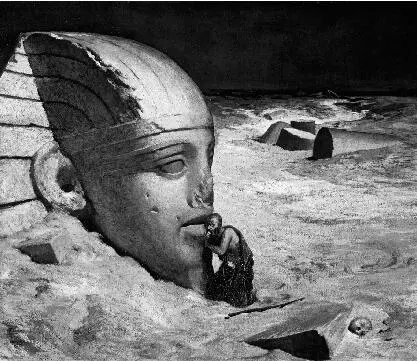

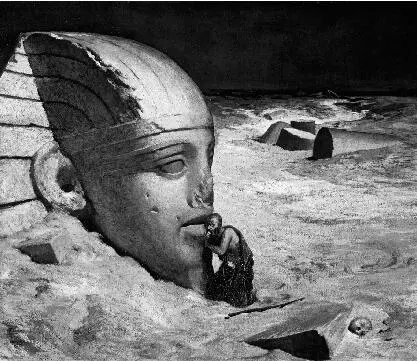

Thinking about places like the Hump, the Devil’s Chimney, The Lightning Field (or, for that matter, sites such as Angkor Wat or Borobudur), I keep coming back to the painting that I saw in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston on the day I’d hoped to see Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Elihu Vedder’s The Questioner of the Sphinx (1863) shows a dark-skinned wanderer or traveller, ear pressed against the head of the sphinx that emerges from the sea of sand in which it has been submerged for centuries. Apart from a few broken columns and a human skull (an earlier questioner?), nothing besides remains. In a way it’s an early depiction of the post-apocalyptic world (the sky is black but it doesn’t seem like night), a reminder, painted in the midst of the American Civil War, that plenty of civilizations before our own have suffered apocalyptic extinction. One could easily imagine that it’s not the head of the sphinx poking above the sand but the torch of the Statue of Liberty, Planet of the Apes —style. Vedder was in his twenties when he did this painting. He had not been to Egypt but had seen illustrations of the Sphinx at Gizeh. His painting seems emblematic of the experiences that crop up repeatedly in this book: of trying to work out what a certain place — a certain way of marking the landscape — means; what it’s trying to tell us; what we go to it for.

Time in Space

Maybe it is not the natives of Texas or Arizona who fully appreciate the scale of the places where they have grown up. Perhaps you have to be British, to come from ‘an island no bigger than a back garden’—in Lawrence’s contemptuous phrase — to grasp properly the immensity of the American West. So it’s not surprising that Lawrence considered New Mexico ‘the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had.’

The cramped paradox of English life: a tiny island that is often hard and sometimes impossible to get around. You can imagine a prospective visitor from Arizona studying a map of England and deciding, ‘Yep, we should be able to do this little puppy in a couple of days.’ But how long does it take to travel from Gloucester to Heathrow? Anything from two and a half hours to. . Well, best to allow five to be on the safe side.

In the American West you can travel hundreds of miles and calculate your arrival time almost to the minute. We had turned up for our rendezvous in Quemado at one o’clock on the dot. From Quemado, Jessica and I drove 450 miles to Springdale, on the edge of Zion, in Utah. There were just two of us now, a husband-and-wife team, and we got to Springdale exactly on time for our dinner reservation. After a couple of nights in Zion we headed to the Spiral Jetty .

Yes, the Spiral Jetty —the wholly elusive grail of Land Art! Instantly iconic, it was transformed into legend by a double negative: the disappearance of the Jetty a mere two years after it was created, followed, a year later, by the premature death of its creator, Robert Smithson. Water levels at the Great Salt Lake in northern Utah were unusually low when the Jetty was built in 1970. When the water returned to its normal depth the Jetty went under. On 20 July 1973, Smithson was in a light aircraft, reconnoitering a work in progress in Amarillo, Texas. The plane ploughed into a hillside, killing everyone onboard: the pilot, a photographer, and the artist. Smithson was thirty-five. After the Jetty sank and his plane crashed, Smithson’s reputation soared.

For a quarter of a century the Spiral Jetty was all but invisible. There were amazing photographs of the coils of rock in the variously coloured water — reddish, pink, pale blue — and there was the Zapruder-inflected footage of its construction, but the Jetty had gone the way of Atlantis, sinking beneath the waveless waves of the Salt Lake. Then, in 1999, a miracle occurred. Excalibur-like, it emerged from the lake. And not only that. The Jetty was made out of earth and black lumps of basalt (six and a half thousand tonnes of it), but during the long interval of its submersion it had become covered in salt crystals. In newly resurrected form, it was pristine glittering white.

Even now, after this spectacular renaissance, the Spiral Jetty is not always visible. If there is exceptionally heavy snowfall, then the thaw does for the lake what the globally heated polar ice pack threatens to do to the oceans. Once the snowmelt ends up in the lake, it can take months of drought and scorch to boil off the excess and leave the Jetty high and dry again. Was it worth travelling all this way to see something we might not be able to see? Well, pilgrims continued to turn up even during the long years when there was definitely nothing to see, so it seemed feeble not to give it a chance. (There is probably a sect of art-world extremists who maintain that the best time to have visited the Spiral Jetty was during the years of its invisible submergence, when the experience became a pure manifestation of faith.)

We drove north towards Salt Lake City. No need for a compass. Everything screamed north: the grey-and-white mountains looming Canadianly in the distance, the weather deteriorating by the hour. Opting for directness instead of scenery, we barrelled up the featureless expanse of I-15. Most of what there was to see was traffic-related: gas-station logos, trucks the size of freight trains, snakeskin shreds of tire on the soft (‘hard’ in England) shoulder. Salt Lake City did its bit, its level best, coming to meet us well before we got anywhere near it — and not quite saying goodbye even when we thought we’d got beyond it.

Читать дальше