She took me up to the third floor, where a giant screen covered one wall, with a row of cushy reclining chairs facing it. This was a “dacha” in the same sense that a Cadillac limousine is a “car,” and as I oohed and aahed my way around, Anya smiled, seeming pleased.

Sergei and Lyuba’s place was a short walk away, past a banya, through a gate, then past a fire pit and gazebo. Their dacha was equally huge, and the interior was chockablock with art, tchotchkes, and shelves full of books. Lyuba shuffled about the kitchen in a purple housedress and slippers while Sergei gave me the tour.

Like Anya’s, this dacha had multiple bedrooms, all of them—as Sergei proudly pointed out—with en suite bathrooms. “The builders told me it would be impossible for each room to have its own bathroom, because of the plumbing,” he said. “But I insisted. And now my friends all ask for pictures so they can show their own architects that it can be done.” He showed me his “man cave,” a book-lined study with curved walls and a view of the lake, and back down on the first floor, the indoor swimming pool. I thought of Anya’s grandmother’s joke, and while Putin probably does have a bigger dacha, you could totally have him over to this one and not feel self-conscious.

Sergei’s hair and mustache had grayed, but other than that he looked great—slimmer than in 2005, and with a perpetual grin on his ruddy face. As we waited for Lyuba to finish making dinner, he fetched a Russian army officer’s hat and thrust it into my hands. “Try it on!” he said. I did, and saluted—not like a Pionerka, that much I knew—while Sergei guffawed. He disappeared and returned with a cowboy hat bearing a silver sheriff’s star, and we giggled and took photos together in the opulent living room. For a man who’d made so much money and lived in relative splendor, he gave off the air of your favorite goofy uncle.

Lyuba called us to the table, and we sat down to a meal of pork chops, sliced ham, potato casserole, and that Russian classic: pod shuboy salad. Pod shuboy, or “under a fur coat,” is so named because a layer of herring is covered by an “overcoat” of sliced vegetables, eggs, beets, and mayonnaise. As he took a heaping spoonful, Sergei said, “Lyuba’s pod shuboy is better. Someone else brought us this one.” Then, as if loath to insult an innocent salad, he said, “But you know, this one is OK too.”

We drank wine and champagne out of crystal goblets, while Sergei tossed back vodka shots. The more he drank, the more red-faced and voluble he became, until the evening settled into a rhythm: Sergei would tell a story, waving his arms wildly, and Lyuba would add dry commentary as the rest of us laughed. It was as if we were playing out a Russian version of the sitcom Roseanne .

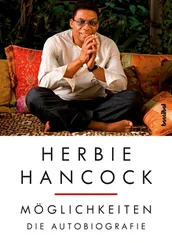

Lyuba and Sergei, posing at their dacha in 2015 with photos from 1995 and 2005 (PHOTO BY LISA DICKEY)

Toward the end of dinner, Sergei wanted to show me some videos from the old days. We settled into the living room to watch, and the first one flickered onto the TV screen: It was from a friend’s fortieth birthday party on October 7, 1995—just three weeks before Gary and I met them. “We’re still friends with that couple… and that guy,” Lyuba said, as the camera panned around the dinner table. “We still see all the same people.”

Then there were videos from the years when Anya and Masha were children. The girls wore stretchy knit pants over their diapers, and in nearly every clip, Masha was eating, and little Anya was mimicking washing clothes. “Why am I always washing?” Anya asked, laughing. “And why are our dresses so short?” It was true—in every scene, the girls’ little dresses barely came past their hips. “Ah, that was the style then,” said Lyuba, laconically.

It occurred to me that Sergei and Lyuba had told the truth, that if you plopped them down anywhere—into a 1970s communalka , say, or a Tsarist village—they’d behave no differently than now. They made corny jokes (Sergei: “I lost ten kilograms… and Lyuba found it!”) while the dogs scrabbled around and barked. They were quick to laugh at themselves, and at each other. At one point, Sergei announced that he had a piece of the Chelyabinsk meteor, [3] Thousands of tiny fragments of the meteor were found in the area around Chelyabinsk, many of which were boxed up and sold as souvenirs.

and after rummaging around upstairs for ten minutes, he came back down and proudly handed me a small, clear plastic container with a sliver of gray rock. “That’s not it!” exclaimed Lyuba. “That’s a piece of the Berlin Wall.”

“Ah, so it is,” said Sergei, peering closer. “Well, they do look kind of similar.” Then he broke out into that familiar grin, exclaiming, “Anyway—look, Liza! A piece of the Berlin Wall!” Lyuba rolled her eyes.

* * *

The next morning, Anya, Max, and I took a stroll to Lake Chebarkul, to see where the largest chunk of the meteor had fallen. As we walked through a light snowfall, Anya told me that she’d spoken with Masha. “She didn’t sleep at all last night,” she said. “She’s worried that she said too much at lunch, or was too vehement.”

“Ah, she was fine,” I replied. “She’s a patriot of her country. We all are.” In truth, I had been startled at the depth of Masha’s anger, but the fact that she’d expressed concern soothed whatever raw feelings I had left. In Anya’s view, Masha had become more fervent about politics since her son had been born, which I could understand. And while I disagreed with much of what Masha believed, I was grateful she’d said it so plainly. I suspected that many of the Russians I’d been spending time with felt the same way, but were afraid of offending the American visitor. Yet I much preferred to hear the truth about what people thought, rather than a sanitized version.

Later that afternoon, I got my wish. Max cooked shashlik on an outdoor grill, and the five of us dined in a freestanding glass-walled dining room a short walk from the dacha. Somehow, we got on the subject of racism.

Sergei and Lyuba started talking about the Arabic population in France—specifically, why they didn’t make an effort to assimilate, rather than continuing to follow their own customs. “They come to another county and then behave as they would at home,” he said. “When I’m in another country, I try to behave according to its standards.” I opined that while a certain degree of assimilation was helpful, it wasn’t necessary for immigrants to abandon their own culture for that of their host country. Both Sergei and Lyuba disagreed, saying that there were certain standards of behavior people needed to follow.

He then told a story about an encounter on one of his many trips to the United States. “I was riding a bus, and there was a black guy next to me,” he said. “When I got up for a minute, he slumped over and took up my seat.” This made Sergei angry, and he wanted to throw the man off the bus. But when he confronted the man, “other black people on the bus, in the back, started to make menacing comments.” Sergei didn’t want to back down, but “then a white guy up front said, ‘You’d better come up here.’” He did, though he was furious.

“If I had been in my own country, I would have happily thrown that guy off the bus,” he said. “If he was white, nobody would have cared. But in America, people practice reverse racism. Nobody will confront a black person, because they’re too scared something will happen.” I ventured that the history of race relations in America was long and complicated, and that it continued to infuse modern race relations, but even as the words came out of my mouth, I knew they sounded like so much liberal mush to Sergei. He shook his head. “People should behave properly, no matter their race.”

Читать дальше