A visitor to Birobidzhan during the Brezhnev era might hear older men speaking Yiddish in the park, but apart from that, not much marked this place as a onetime Jewish homeland. Glasnost led to a modest revival of Jewish culture in the 1980s, but it also led to a new, possibly final, exodus, as thousands of Jews took advantage of newly relaxed travel laws to leave the country. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the floodgates truly opened, and thousands more streamed out, including most of the remaining Jews of Birobidzhan. By the end of 1992, fewer than 5,000 Jews were left here.

So, when Gary and I arrived in Birobidzhan in September 1995, we weren’t sure how much—if any—Jewish culture we’d find. I asked around to see if there was a synagogue in town, but nobody seemed to know. A taxi driver agreed to take us on a search, and after driving in circles, we managed to find a small wooden building with wrought-iron Stars of David in the windows. I knocked on the door, and a short, white-bearded man wearing a yarmulke answered.

This was Boris Kaufman, the self-appointed keeper of what turned out to be Birobidzhan’s only synagogue. There was no rabbi in Birobidzhan, Boris told us, so there were no official prayer services here. But twice a week, he led services for a small group of mostly elderly women. “Please join us for the next one, if you’d like,” he said. We eagerly accepted, excited to witness a service in this historic remnant of the once-thriving Jewish Autonomous Region.

When Gary and I arrived at the appointed time, Boris asked me to put on a headscarf. I wasn’t familiar with Jewish rituals, so I didn’t think anything of it, but once the service started it quickly became clear that Boris was making up his own rules. Because what we ended up witnessing was more evangelical tent revival than Jewish service.

Boris read from a Hebrew prayer book, shuddering and rocking back and forth in apparent religious ecstasy, while the old women, weeping and waving their hands, called out verses from the New Testament. “Jesus said, ‘I am the way, the truth and life!’” one shouted, as Boris rocked in his chair, a little smile on his lips. It was a jarring scene, as Boris later acknowledged. “Perhaps it bothers some people that we worship Jesus here; I don’t know. I’ve never asked them,” he told me. “But it’s not as though we took over the synagogue from Jews who wanted to hold services. The generation of older Jews who used to come gradually died out, and no one else came to fill the void.”

Boris Kaufman at the old synagogue, 1995 (PHOTO BY GARY MATOSO)

Yet Boris, who was ethnically Jewish, also told us he wanted to see Birobidzhan’s Jewish culture preserved. Every morning before the sun rose, he and his mentor, a twenty-something former Yeshiva student named Oleg Shavulski, sang Jewish prayers. A slender, sad-eyed man with a neatly trimmed beard, Oleg taught Boris how to wear the tefillin and translated Hebrew words the older man didn’t know. When we asked about the Jesus-worshiping gatherings in the synagogue, he sighed heavily. “Boris is confused,” he said. “But he will come around eventually. One does not come to the truth in one day or two days. It takes many days.”

Oleg was one of the most vocal proponents of revitalizing Jewish culture in Birobidzhan. He told us there were promising signs: Sunday school classes (taught by Oleg) had started up again, a new cultural center had opened, and School No. 2 was not only offering Yiddish classes again, they were also putting on a Rosh Hashanah pageant the following week.

Yet it was hard to avoid the feeling that this was too little, too late. With no rabbi, no functioning synagogue, and no prospects for getting either anytime soon, how much longer could the city’s Jewish community survive?

For that matter, how long could Birobidzhan itself survive in the face of its shattered economy? In the four years since the collapse of the USSR, factories had closed down, thousands of people had lost their jobs, and many who were still working hadn’t been paid in months. With its tree-lined streets and small-town feel, Birobidzhan wasn’t without its charms, but the lack of employment and a persistent sense of malaise were like a cloud hovering just overhead.

This place was dirt poor, and what little money did trickle in went straight to Sokhnut, an organization whose main purpose here was to help Jews get out. “No one wants to invest any money in this city,” Oleg said bitterly. “The easiest thing in the world is to leave, to quit. But there will always be Jews in Birobidzhan, and we must make it possible for them to have a normal spiritual life. Someone must be here to take care of those who stay.”

This, we discovered, was the central question for Birobidzhan’s Jews in 1995: Stay, and work to revive the city? Or call it a day, and move to Israel (or Europe, or North America)?

Sokhnut director Mikhail Diment, a weary-looking man of 60 whose office was decorated with a large Israeli flag, spent every day working to help people leave. “We are the one race that knows exactly where it came from,” he told me. “We are linked by faith, by the Torah. And Israel is our homeland.” Those who wanted to leave, he said, should feel no guilt for doing so.

Author David Waiserman, who was born and raised in Birobidzhan, was dismayed by the mass exodus. “The Jews who are leaving this city are leaving for one reason: economics,” he told me. “They got a call from somebody in Israel who said, ‘Hey, Moishe! Get over here and have a look at this place! They got nice cars here, and great food!’ So the people go.” He paused. “But my parents built this city. They are lying in its graveyard. How can I just pick up and go? This is where my roots are.”

Maria Shokhtova, a Yiddish teacher at School No. 2, told me that during her childhood in Ukraine, her father prayed “every morning and every night. He knew all the rituals, and we used to go to the synagogue.” But these days, she didn’t do any of those things—and she didn’t know anyone else who did, either. “I live in a little village called Waldheim with my daughter now,” she told me. “When we first came to Waldheim, it was all Jewish. Now you can hardly find any Jews there.” [1] Valdgeym , as it’s called in Russian, was the site of the Jewish Autonomous Region’s first collective farm ( kolkhoz ), founded in 1928.

Alexander Yakubson, a 48-year-old lawyer, was truly torn about what to do. He and his family had emigrated to Israel in 1991, then returned to Birobidzhan three years later to find it a changed place. “When we left Russia in 1991, the economy was more stable, the factories were still working. There was almost no crime,” he said. “When we returned last year, the picture was totally different. There are so many unemployed here now, so many people are poor. Now the Russians envy the Jews in this country, because the Jews can leave.”

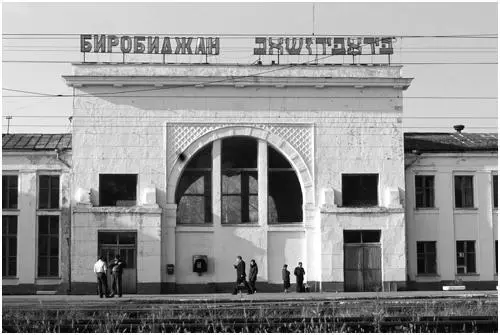

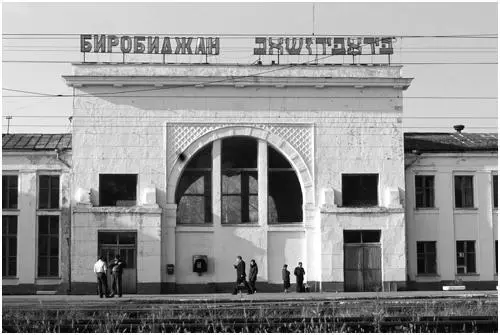

Birobidzhan train station sign, written in Russian and Yiddish, 1995 (PHOTO BY GARY MATOSO)

“My wife wants to go back to Israel,” he said. “I’m not sure what I want.”

Hearing the anguish in his voice, I couldn’t help but think that perhaps when you have two homelands, you really have none. Because you never know where you truly belong.

* * *

I titled my 1995 story “The Last Jews of Birobidzhan,” and as the 2005 trip drew near, I expected to find little more than a ghost town here, at least in terms of Jewish culture.

Читать дальше