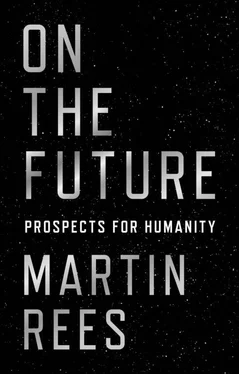

Yet long-term goals tend to slip down the political agenda, trumped by immediate problems—and a focus on the next election. The president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, said, ‘We all know what to do; we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it’. [8]He was referring to financial crises, but his remark is even more appropriate for environmental challenges (and it’s playing out now with the discouragingly slow implementation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals).

There is a depressing gap between what could be done and what actually happens. Offering more aid is not in itself enough. Stability, good governance, and effective infrastructure are needed if these benefits are to permeate the developing world. The Sudanese tycoon Mo Ibrahim, whose company led the penetration of mobile phones into Africa, in 2007 set up a prize of $5 million (plus $200,000 a year thereafter) to recognise exemplary and noncorrupt leaders of African countries—and the Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership has been awarded five times.

The relevant actions aren’t necessarily best taken at the nation-state level. Some of course require multinational cooperation, but many effective reforms need implementation more locally. There are huge opportunities for enlightened cities to become pathfinders, spearheading the high-tech innovation that will be needed in the megacities of the developing world where the challenges are especially daunting.

Short-termism isn’t just a feature of electoral politics. Private investors don’t have a long enough horizon either. Property developers won’t put up a new office building unless they get payback within (say) thirty years. Indeed, most high-rise buildings in cities have a ‘designed lifetime’ of only fifty years (a consolation for those of us who deplore their dominance of the skyline). Potential benefits and downsides beyond that time horizon are discounted away.

What about the more distant future? Population trends beyond 2050 are harder to predict. They will depend on what today’s young people, and those as yet unborn, will decide about the number and spacing of their children. Enhanced education and empowerment of women—surely a priority in itself—could reduce fertility rates where they’re now highest. But this demographic transition hasn’t yet reached parts of India and sub-Saharan Africa.

The mean number of births per woman in some parts of Africa—Niger, or rural Ethiopia, for instance—is still more than seven. Although fertility is likely to decrease, it is possible, according to the United Nations, that Africa’s population could double again to four billion between 2050 and 2100, thereby raising the global population to eleven billion. Nigeria alone would then have as large a population as Europe and North America combined, and almost half of all the world’s children would be in Africa.

Optimists remind us that each extra mouth brings also two hands and a brain. Nonetheless, the greater the population becomes, the greater will be the pressures on resources, especially if the developing world narrows its gap with the developed world in its per capita consumption. And the harder it will be for Africa to escape the ‘poverty trap’. Indeed, some have noted that African cultural preferences may lead to a persistence of large families as a matter of choice even when child mortality is low. If this happens, the freedom to choose your family size, proclaimed as one of the UN’s fundamental rights, may come into question when the negative externalities of a rising world population are weighed in the balance.

We must hope that the global population declines rather than increases after 2050. Even though nine billion can be fed (with good governance and efficient agribusiness), and even if consumer items become cheaper to produce (via, for instance, 3D printing) and ‘clean energy’ becomes plentiful, food choices will be constrained and the quality of life will be reduced by overcrowding and reductions in green space.

1.4. STAYING WITHIN PLANETARY BOUNDARIES

We’re deep into the Anthropocene. This term was popularised by Paul Crutzen, one of the scientists who determined that the ozone in the upper atmosphere was being depleted by CFCs—chemicals then used in aerosol cans and refrigerators. The 1987 Montreal Protocol led to the ban on these chemicals. This agreement seemed an encouraging precedent, but it worked because substitutes existed for CFCs that could be deployed without great economic costs. Sadly, it’s not so easy to deal with the other (more important) anthropogenic global changes consequent on a rising population, changes that are more demanding of food, energy, and other resources. All these issues are widely discussed. What’s depressing is the inaction—for politicians the immediate trumps the long term; the parochial trumps the global. We need to ask whether nations need to give more sovereignty to new organisations along the lines of the existing agencies under the auspices of the United Nations.

The pressures of rising populations and climate change will engender loss of biodiversity—an effect that would be aggravated if the extra land needed for food production or biofuels encroached on natural forests. Changes in climate and alterations to land use can, in combination, induce ‘tipping points’ that amplify each other and cause runaway and potentially irreversible change. If humanity’s collective impact on nature pushes too hard against what the Stockholm environmentalist Johan Rockström calls ‘planetary boundaries’, [9]the resultant ‘ecological shock’ could irreversibly impoverish our biosphere.

Why does this matter so much? We are harmed if fish populations dwindle to extinction. There are plants in the rain forest that may be useful to us for medicinal purposes. But there is a spiritual value too, over and above the practical benefits of a diverse biosphere. In the words of the eminent ecologist E. O. Wilson,

At the heart of the environmentalist worldview is the conviction that human physical and spiritual health depends on the planet Earth…. Natural ecosystems—forests, coral reefs, marine blue waters—maintain the world as we would wish it to be maintained. Our body and our mind evolved to live in this particular planetary environment and no other. [10]

Extinction rates are rising—we’re destroying the book of life before we’ve read it. For instance, the populations of the ‘charismatic’ mammals have fallen, in some cases to levels that threaten species. Many of the six thousand species of frogs, toads, and salamanders are especially sensitive. And, to quote E. O. Wilson again, ‘if human actions lead to mass extinctions, it’s the sin that future generations will least forgive us for’.

Here, incidentally, the great religious faiths can be our allies. I’m on the council of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences (an ecumenical body; its seventy members represent all faiths or none). In 2014 the Cambridge economist Partha Dasgupta, along with Ram Ramanathan, a climate scientist from the Scripps Institute in California, organised a high-level conference on sustainability and climate held at the Vatican. [11]This offered a timely scientific impetus into the 2015 papal encyclical ‘Laudato Si’. The Catholic Church transcends political divides; there’s no gainsaying its global reach, its durability and long-term vision, or its focus on the world’s poor. The Pope was given a standing ovation at the United Nations. His message resonated especially in Latin America, Africa, and East Asia.

The encyclical also offered a clear papal endorsement of the Franciscan view that humans have a duty to care for all of what Catholics believe is ‘God’s creation’—that the natural world has value in its own right, quite apart from its benefits to humans. This attitude resonates with the sentiments beautifully expressed more than a century ago by Alfred Russel Wallace, co-conceptualiser of evolution by natural selection:

Читать дальше

![Мартин Рис - Всего шесть чисел. Главные силы, формирующие Вселенную [litres]](/books/414169/martin-ris-vsego-shest-chisel-glavnye-sily-formir-thumb.webp)