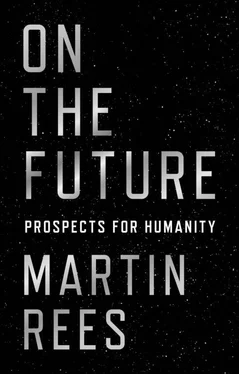

The potentials of biotech and the cyberworld are exhilarating—but they’re frightening too. We are already, individually and collectively, so greatly empowered by accelerating innovation that we can—by design, or as unintended consequences—engender global changes that will resonate for centuries. The smartphone, the web, and their ancillaries are already crucial to our networked lives. But these technologies would have seemed magical even just twenty years ago. So, looking several decades ahead we must keep our minds open, or at least ajar, to transformative advances that may today seem like science fiction.

We can’t confidently forecast lifestyles, attitudes, social structures, or population sizes even a few decades hence—still less the geopolitical context against which these trends will play out. Moreover, we should be mindful of an unprecedented kind of change that could emerge within a few decades. Human beings themselves—their mentality and their physique—may become malleable through the deployment of genetic modification and cyborg technologies. This is a game changer. When we admire the literature and artefacts that have survived from antiquity, we feel an affinity, across a time gulf of thousands of years, with those ancient artists and their civilisations. But we can have zero confidence that the dominant intelligences a few centuries hence will have any emotional resonance with us—even though they may have an algorithmic understanding of how we behaved.

The twenty-first century is special for another reason: it is the first in which humans may develop habitats beyond the Earth. The pioneer ‘settlers’ on an alien world will need to adapt to a hostile environment—and they will be beyond the reach of terrestrial regulators. These adventurers could spearhead the transition from organic to electronic intelligence. This new incarnation of ‘life’, not requiring a planetary surface or atmosphere, could spread far beyond our solar system. Interstellar travel is not daunting to near-immortal electronic entities. If life is now unique to the Earth, this diaspora will be an event of cosmic significance. Yet if intelligence already pervades the cosmos, our progeny will merge with it. This would play out over astronomical timescales—not ‘mere’ centuries. Chapter 3 presents a perspective on these longer-term scenarios: whether robots will supersede ‘organic’ intelligence, and whether such intelligence already exists elsewhere in the cosmos.

What happens to our progeny, here on Earth and perhaps far beyond, will depend on technologies that we can barely conceive today. In future centuries (still an instant in the cosmic perspective), our creative intelligence could jump-start the transitions from an Earth-based to a space-faring species, and from biological to electronic intelligence—transitions that could inaugurate billions of years of posthuman evolution. On the other hand, as discussed in chapters 1and 2, humans could trigger bio, cyber, or environmental catastrophes that foreclose all such potentialities.

Chapter 4offers some (perhaps self-indulgent) excursions into scientific themes—fundamental and philosophical—that raise questions about the extent of physical reality, and whether there are intrinsic limits to how much we’ll ever understand of the real world’s complexities. We need to assess what’s credible, and what can be dismissed as science fiction, in order to forecast the impact of science on humanity’s long-term prospects.

In the final chapter I address issues closer to the here and now. Science, optimally applied, could offer a bright future for the nine or ten billion people who will inhabit the Earth in 2050. But how can we maximise the chance of achieving this benign future while avoiding the dystopian downsides? Our civilisation is moulded by innovations that stem from scientific advances and the consequent deepening understanding of nature. Scientists will need to engage with the wider public and use their expertise beneficially, especially when the stakes will be immensely high. Finally, I address today’s global challenges—emphasising that these may require new international institutions, informed and enabled by well-directed science, but also responsive to public opinion on politics and ethics.

Our planet, this ‘pale blue dot’ in the cosmos, is a special place. It may be a unique place. And we are its stewards in an especially crucial era. That is an important message for all of us—and the theme of this book.

1

DEEP IN THE ANTHROPOCENE

1.1. PERILS AND PROSPECTS

A few years ago, I met a well-known tycoon from India. Knowing I had the English title of ‘Astronomer Royal’, he asked, ‘Do you do the Queen’s horoscopes’? I responded, with a straight face: ‘If she wanted one, I’m the person she’d ask’. He seemed eager to hear my predictions. I told him that stocks would fluctuate, there would be new tensions in the Middle East, and so forth. He paid rapt attention to these ‘insights’. But then I came clean. I said I was just an astronomer—not an astrologer. He abruptly lost all interest in my predictions. And rightly so: scientists are rotten forecasters—almost as bad as economists. For instance, in the 1950s an earlier Astronomer Royal said that space travel was ‘utter bilge’.

Nor do politicians and lawyers have a sure touch. One rather surprising futurologist was F. E. Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, crony of Churchill and the UK’s Lord Chancellor in the 1920s. In 1930 he wrote a book titled The World in 2030 . [1]He’d read the futurologists of his era; he envisaged babies incubated in flasks, flying cars, and such fantasies. In contrast, he foresaw social stagnation. Here’s a quote: ‘In 2030 women will still, by their wit and charms, inspire the most able men towards heights that they could never themselves achieve’.

Enough said!

* * *

Back in 2003 I wrote a book which I titled Our Final Century? My UK publisher deleted the question mark. The American publishers changed the title to Our Final Hour . [2]My theme was this: Our Earth is forty-five million centuries old. But this century is the first in which one species—ours—can determine the biosphere’s fate. I didn’t think we’d wipe ourselves out. But I did think we’d be lucky to avoid devastating breakdowns. That’s because of unsustainable stresses on ecosystems; there are more of us (world population is higher) and we’re all more demanding of resources. And—even more scary—technology empowers us more and more, and thereby exposes us to novel vulnerabilities.

I was inspired by, among others, a great sage of the early twentieth century. In 1902 the young H. G. Wells gave a celebrated lecture at the Royal Institution in London. [3]‘Humanity’, he proclaimed,

has come some way, and the distance we have travelled gives us some insight of the way we have to go…. It is possible to believe that all the past is but the beginning of a beginning, and that all that is and has been is but the twilight of the dawn. It is possible to believe that all that the human mind has accomplished is but the dream before the awakening; out of our lineage, minds will spring that will reach back to us in our littleness to know us better than we know ourselves. A day will come, one day in the unending succession of days, when beings, beings who are now latent in our thoughts and hidden in our loins, shall stand upon this earth as one stands upon a footstool, and shall laugh and reach out their hands amidst the stars.

His rather purple prose still resonates more than a hundred years later—he realised that we humans aren’t the culmination of emergent life.

But Wells wasn’t an optimist. He also highlighted the risk of global disaster:

Читать дальше

![Мартин Рис - Всего шесть чисел. Главные силы, формирующие Вселенную [litres]](/books/414169/martin-ris-vsego-shest-chisel-glavnye-sily-formir-thumb.webp)