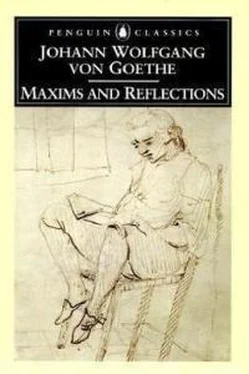

Иоганн Гёте - Maxims and Reflections

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Иоганн Гёте - Maxims and Reflections» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Maxims and Reflections

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Maxims and Reflections: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Maxims and Reflections»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Maxims and Reflections — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Maxims and Reflections», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The element of moral teaching which runs through Goethe's mature works like a golden thread, re–appears in the maxims free and detached from the poetic and romantic environment which in such varied shapes is woven around it in Werther, Tasso, Meister , above all in Faust . To do the next duty; to meet the claims of each day; to persist with a single mind and unwearied effort on a definite, positive, productive path; cheerfully to renounce what is denied us, and vigorously to make the best of what we have; to restrain vague desires and uncertain aims; to cease bewailing the vanity of all things and the fleeting nature of this our world, and do what we can to make our stay in it of lasting use,—these are lessons which will always be needed, and all the more needed as life becomes increasingly complex. They are taught in the maxims with a great variety of application, and nowhere so concisely summarised as in one of them. "The mind endowed with active powers," so it runs, "and keeping with a practical object to the task that lies nearest, is the worthiest there is on earth."

Goethe has been called, and with truth, the prophet of culture; but the word is often misunderstood. We cannot too clearly see that what is here meant is not a mere range of intellectual knowledge, pursued with idolatrous devotion: it is moral discipline, a practical endeavour, forming wise thought and noble character. And this is the product, not of learning, but of work: if we are to know and realise what there is in us, and make the best of it, our aim must be practical and creative. "Let every man," he urges, "ask himself with which of his faculties he can and will somehow influence his age." And again: "From this time forward, if a man does not apply himself to some art or handiwork, he will be in a bad way. In the rapid changes of the world, knowledge is no longer a furtherance. By the time a man has taken note of everything, he has lost himself." The culture of which he speaks is not mainly intellectual. We use the word in a way that is apt to limit and conceal its meaning, and we often apply it to a strange form of mental growth, at once stunted and overfed, to which, if we may judge by its fruits, any breath of real culture would be fatal. It has nothing to do with learning in the general and narrow sense of the word, or with the often pernicious effects of mere learning. In the language of the hour we are wont to give the exclusive name of culture to a wide acquaintance with books and languages; whether or not it results, as it has before now resulted, in a want of culture in character and outward demeanour, in airs of conceit, in foolish arrogance, in malice and acrimony.

A uniform activity with a moral aim—that, in Goethe's view, is the highest we can achieve in life. "Character in matters great and small consists," he says, "in a man steadily pursuing the things of which he feels himself capable." It is the gospel of work: our endeavour must be to realise our best self in deed and action; to strive until our personality attains, in Aristotle's word, its entelechy; its full development. By this alone can we resolve all the doubts and hesitations and conflicts within that undermine and destroy the soul. "Try to do your duty, and you will know at once what you are worth." And with all our doing, what should be the goal of our activity? In no wise our own self, our own weal. "A man is happy only when he delights in the good–will of others," and we must of a truth "give up existence in order to exist"; we must never suppose that happiness is identical with personal welfare. In the moral sphere we need, as Kant taught, a categorical imperative; but, says Goethe, that is not the end of the matter; it is only the beginning. We must widen our conception of duty and recognise a perfect morality only "where a man loves what he commands himself to do." "Voluntary dependence is the best state, and how should that be possible without love?" And just in the same sense Goethe refuses to regard all self–denial as virtuous, but only the self–denial that leads to some useful end. All other forms of it are immoral, since they stunt and cramp the free development of what is best in us—the desire, namely, to deal effectively with our present life, and make the most and fairest of it.

And here it is that Goethe's moral code is fused with his religious belief. "Piety," he says, "is not an end but a means: a means of attaining the highest culture by the purest tranquillity of soul." This is the piety he preaches; not the morbid introspection that leads to no useful end, the state of brooding melancholy, the timorous self–abasement, the anxious speculation as to some other condition of being. And this tranquillity of soul, Goethe taught that it should be ours, in spite of the thousand ills of life which give us pause in our optimism. It is attained by the firm assurance that, somewhere and somehow, a power exists that makes for moral good; that our moral endeavours are met, so to speak, half–way by a moral order in the universe, which comes to the aid of individual effort. And the sum and substance of his teaching, whether in the maxims or in any other of his mature productions, is that we must resign ourselves to this power, in gratitude and reverence towards it and all its manifestations in whatever is good and beautiful. This is Goethe's strong faith, his perfect and serene trust. He finely shadows it forth in the closing words of Pandora , where Eos proclaims that the work of the gods is to lead our efforts to the eternal good, and that we must give them free play:—

Was zu wünschen ist, ihr unten fühlt es;

Was zu geben sei, die wissen's droben.

Gross beginnet ihr Titanen; aber leiten

Zu dem ewig Guten, ewig Schönen,

Ist der Götter Werk; die lasst gewähren.

And so too in Faust : it is the long struggle to realise an Ideal, dimly seen on life's labyrinthine way of error, that leads at last to the perfect redemption:—

Wer immer strebend sich bemüht,

Den können wir erlösen.

And throughout the perplexities of life and the world, where all things are but signs and tokens of some inner and hidden reality, it is the ideal of love and service, das Ewig–Weibliche , that draws us on.

But this assurance cannot be reached by a mere theory; and Goethe is not slow to declare how he views attempts to reach it in that way. " Credo Deum! that," he reminds us here, "is a fine, a worthy thing to say; but to recognise God when and where he reveals himself, is the only true bliss on earth." All else is mystery. We are not born, as he said to Eckermann, to solve the problems of the world, but to find out where the problem begins, and then to keep within the limits of what we can grasp. The problem, he urged, is transformed into a postulate: if we cannot get a solution theoretically, we can get it in the experience of practical life. We reach it by the use of an "active scepticism," of which he says that "it continually aims at overcoming itself and arriving by means of regulated experience at a kind of conditioned certainty." But he would have nothing to do with doctrinal systems, and, like Schiller, professed none of the forms of religion from a feeling of religion itself. To see how he views some particular questions of theology the reader may turn with profit to his maxims on the Reformation and early Christianity, and to his admirable remarks on the use and abuse of the Bible. The basis of religion was for him its own earnestness; and it was not always needful, he held, for truth to take a definite shape: "it is enough if it hovers about us like a spirit and produces harmony." "I believe," he said to Eckermann, "in God and Nature and the victory of good over evil; but I was also asked to believe that three was one, and one was three. That jarred upon my feeling for truth; and I did not see how it could have helped me in the least." As for letting our minds roam beyond this present life, he thought there was actual danger in it; although he looked for a future existence, a continuation of work and activity, in which what is here incomplete should reach its full development. And whatever be the secrets of the universe, assuredly the best we can do is to do our best here; and the worst of blasphemies is to regard this life as altogether vanity; for as these pages tell us, "it would not be worth while to see seventy years if all the wisdom of this world were foolishness with God."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Maxims and Reflections»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Maxims and Reflections» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Maxims and Reflections» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Иоганн Гёте - Итальянское путешествие [litres]](/books/398657/iogann-gete-italyanskoe-puteshestvie-litres-thumb.webp)