Ben Goldacre - Bad Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ben Goldacre - Bad Science» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Bad Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bad Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Bad Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Bad Science — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Bad Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

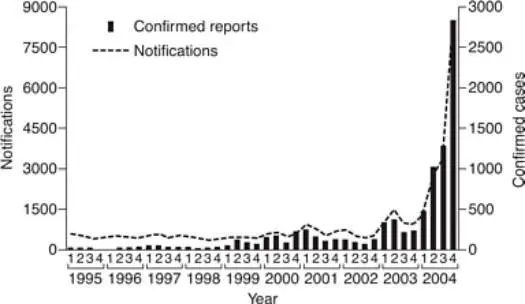

Mumps began rising again in 1999, after many years of cases in only double figures: by 2005 the United Kingdom had a mumps epidemic, with around 5,000 notifications in January alone.

A lot of people who campaign against vaccines like to pretend that they don’t do much good, and that the diseases they protect against were never very serious anyway. I don’t want to force anyone to have their child vaccinated, but equally I don’t think anyone is helped by misleading information. By contrast with the unlikely event of autism being associated with MMR, the risks from measles, though small, are real and quantifiable. The Peckham Report on immunisation policy, published shortly after the introduction of the MMR vaccine, surveyed the recent experience of measles in Western countries and estimated that for every 1,000 cases notified, there would be 0.2 deaths, ten hospital admissions, ten neurological complications and forty respiratory complications. These estimates have been borne out in recent minor epidemics in the Netherlands (1999: 2,300 cases in a community philosophically opposed to vaccination, three deaths), Ireland (2000: 1,200 cases, three deaths) and Italy (2002: three deaths). It’s worth noting that plenty of these deaths were in previously healthy children, in developed countries, with good healthcare systems.

Though mumps is rarely fatal, it’s an unpleasant disease with unpleasant complications (including meningitis, pancreatitis and sterility). Congenital rubella syndrome has become increasingly rare since the introduction of MMR, but causes profound disabilities including deafness, autism, blindness and mental handicap, resulting from damage to the foetus during early pregnancy.

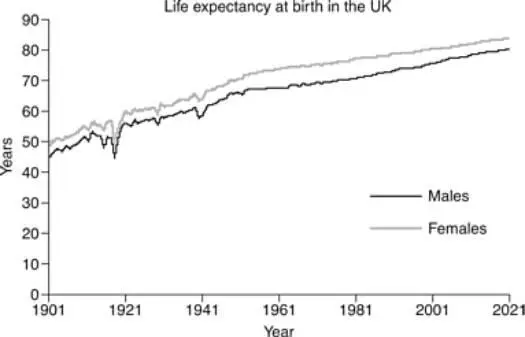

The other thing you will hear a lot is that vaccines don’t make much difference anyway, because all the advances in health and life expectancy have been due to improvements in public health for a wide range of other reasons. As someone with a particular interest in epidemiology and public health, I find this suggestion flattering; and there is absolutely no doubt that deaths from measles began to fall over the whole of the past century for all kinds of reasons, many of them social and political as well as medical: better nutrition, better access to good medical care, antibiotics, less crowded living conditions, improved sanitation, and so on.

Life expectancy in general has soared over the past century, and it’s easy to forget just how phenomenal this change has been. In 1901, males born in the UK could expect to live to forty-five, and females to forty-nine. By 2004, life expectancy at birth had risen to seventy-seven for men, and eighty-one for women (although of course much of the change is due to reductions in infant mortality).

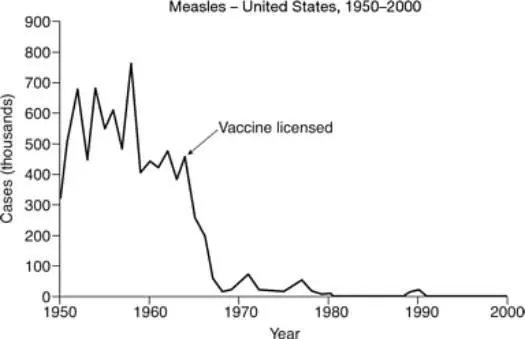

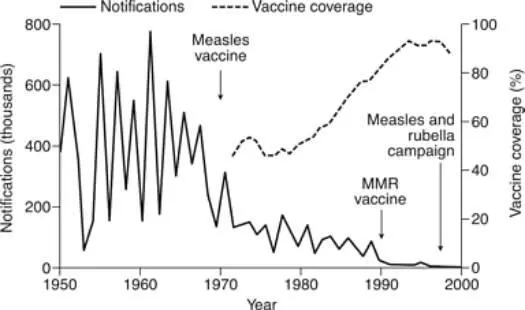

So we are living longer, and vaccines are clearly not the only reason why. No single change is the reason why. Measles incidence dropped hugely over the preceding century, but you would have to work fairly hard to persuade yourself that vaccines had no impact on that. Here, for example, is a graph showing the reported incidence of measles from 1950 to 2000 in the United States.

For those who think that single vaccines for the components of MMR are a good idea, you’ll notice that these have been around since the 1970s, but that a concerted programme of vaccination – and the concerted programme of giving all three vaccinations in one go as MMR – is fairly clearly associated in time with a further (and actually rather definitive) drop in the rate of measles cases.

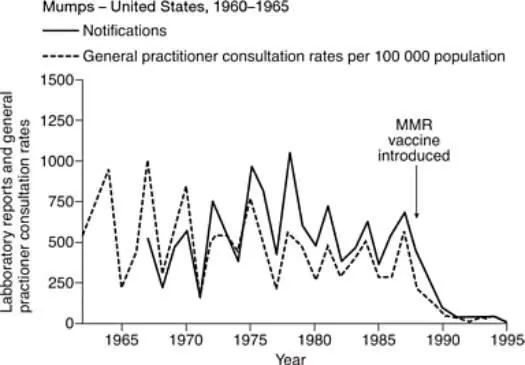

The same is true for mumps:

While we’re thinking about mumps, let’s not forget our epidemic in 2005, a resurgence of a disease many young doctors would struggle even to recognise. Here is a graph of mumps cases from the BMJ article that analysed the outbreak:

Almost all confirmed cases during this outbreak were in people aged fifteen to twenty-four, and only 3.3 per cent had received the full two doses of MMR vaccine. Why did it affect these people? Because of a global vaccine shortage in the early 1990s.

Mumps is not a harmless disease. I’ve no desire to scare anyone – and as I said, your beliefs and decisions about vaccines are your business; I’m only interested in how you came to be so incredibly misled – but before the introduction of MMR, mumps was the commonest cause of viral meningitis, and one of the leading causes of hearing loss in children. Lumbar puncture studies show that around half of all mumps infections involve the central nervous system. Mumps orchitis is common, exquisitely painful, and occurs in 20 per cent of adult men with mumps: around half will experience testicular atrophy, normally in only one testicle, but 15 to 30 per cent of patients with mumps orchitis will have it in both testicles, and of these, 13 per cent will have reduced fertility.

I’m not just spelling this out for the benefit of the lay reader: by the time of the outbreak in 2005, young doctors needed to be reminded of the symptoms and signs of mumps, because it had been such an uncommon disease during their training and clinical experience. People had forgotten what these diseases looked like, and in that regard vaccines are a victim of their own success – as we saw in our earlier quote from Scientific American in 1888, five generations ago (see page 276).

Whenever we take a child to be vaccinated, we’re aware that we are striking a balance between benefit and harm, as with any medical intervention. I don’t think vaccination is all that important: even if mumps orchitis, infertility, deafness, death and the rest are no fun, the sky wouldn’t fall in without MMR. But taken on their own, lots of other individual risk factors aren’t very important either, and that’s no reason to abandon all hope of trying to do something simple, sensible and proportionate about them, gradually increasing the health of the nation, along with all the other stuff you can do to the same end.

It’s also a question of consistency. At the risk of initiating mass panic, I feel duty bound to point out that if MMR still scares you, then so should everything in medicine, and indeed many of the everyday lifestyle risk exposures you encounter: because there are a huge number of things which are far less well researched, with a far lower level of certainty about their safety. The question would still remain of why you were so focused on MMR. If you wanted to do something constructive about this problem, instead of running a single-issue campaign about MMR you might, perhaps, use your energies more usefully. You could start a campaign for constant automated vigilance of the entirety of the NHS health records dataset for any adverse outcomes associated with any intervention, for example, and I’d be tempted to join you on the barricades.

But in many respects this isn’t about risk management, or vigilance: it’s about culture, human stories, and everyday human harms. Just as autism is a peculiarly fascinating condition to journalists, and indeed to all of us, vaccination is similarly inviting as a focus for our concerns: it’s a universal programme, in conflict with modern ideas of ‘individualised care’; it’s bound up with government; it involves needles going into children; and it offers the opportunity to blame someone, or something, for a dreadful tragedy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Bad Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Bad Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Bad Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Роман Зыков - Роман с Data Science. Как монетизировать большие данные [litres]](/books/438007/roman-zykov-roman-s-data-science-kak-monetizirova-thumb.webp)