Ben Goldacre - Bad Science

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ben Goldacre - Bad Science» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Bad Science

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bad Science: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Bad Science»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Bad Science — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Bad Science», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The alternative therapy literature is certainly riddled with incompetence, but flaws in trials are actually very common throughout medicine. In fact, it would be fair to say that all research has some ‘flaws’, simply because every trial will involve a compromise between what would be ideal, and what is practical or cheap. (What sets the CAM literature apart is, in some respects, the interpretation: medics sometimes know if they’re quoting duff papers, and describe the flaws, whereas homeopaths tend to be uncritical of anything positive.)

That is why it’s important that research is always published, in full, with its methods and results available for scrutiny. This is a recurring theme in this book, and it’s important, because when people make claims based upon their research, we need to be able to decide for ourselves how big the ‘methodological flaws’ were, and come to our own judgement about whether the results are reliable, whether theirs was a ‘fair test’. The things that stop a trial from being fair are, once you know about them, blindingly obvious.

Blinding

One important feature of a good trial is that neither the experimenters nor the patients know if they got the homeopathy sugar pill or the simple placebo sugar pill, because we want to be sure that any difference we measure is the result of the difference between the pills, and not of people’s expectations or biases. If the researchers knew which of their beloved patients were having the real and which the placebo pills, they might give the game away – or it might change their assessment of the patient – consciously or unconsciously.

Let’s say I’m doing a study on a medical pill designed to reduce high blood pressure. I know which of my patients are having the expensive new blood pressure pill, and which are having the placebo. One of the people on the swanky new blood pressure pills comes in and has a blood pressure reading that is way off the scale, much higher than I would have expected, especially since they’re on this expensive new drug. So I recheck their blood pressure, ‘just to make sure I didn’t make a mistake’. The next result is more normal, so I write that one down, and ignore the high one.

Blood pressure readings are an inexact technique, like ECG interpretation, X-ray interpretation, pain scores, and many other measurements that are routinely used in clinical trials. I go for lunch, entirely unaware that I am calmly and quietly polluting the data, destroying the study, producing inaccurate evidence, and therefore, ultimately, killing people (because our greatest mistake would be to forget that data is used for serious decisions in the very real world, and bad information causes suffering and death).

There are several good examples from recent medical history where a failure to ensure adequate ‘blinding’, as it is called, has resulted in the entire medical profession being mistaken about which was the better treatment. We had no way of knowing whether keyhole surgery was better than open surgery, for example, until a group of surgeons from Sheffield came along and did a very theatrical trial, in which bandages and decorative fake blood squirts were used, to make sure that nobody could tell which type of operation anyone had received.

Some of the biggest figures in evidence-based medicine got together and did a review of blinding in all kinds of trials of medical drugs, and found that trials with inadequate blinding exaggerated the benefits of the treatments being studied by 17 per cent. Blinding is not some obscure piece of nitpicking, idiosyncratic to pedants like me, used to attack alternative therapies.

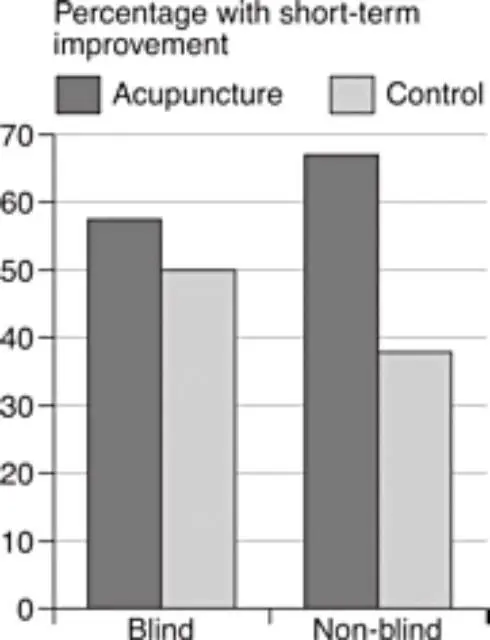

Closer to home for homeopathy, a review of trials of acupuncture for back pain showed that the studies which were properly blinded showed a tiny benefit for acupuncture, which was not ‘statistically significant’ (we’ll come back to what that means later). Meanwhile, the trials which were not blinded – the ones where the patients knew whether they were in the treatment group or not – showed a massive, statistically significant benefit for acupuncture. (The placebo control for acupuncture, in case you’re wondering, is sham acupuncture, with fake needles, or needles in the ‘wrong’ places, although an amusing complication is that sometimes one school of acupuncturists will claim that another school’s sham needle locations are actually their genuine ones.)

So, as we can see, blinding is important, and not every trial is necessarily any good. You can’t just say, ‘Here’s a trial that shows this treatment works,’ because there are good trials, or ‘fair tests’, and there are bad trials. When doctors and scientists say that a study was methodologically flawed and unreliable, it’s not because they’re being mean, or trying to maintain the ‘hegemony’, or to keep the backhanders coming from the pharmaceutical industry: it’s because the study was poorly performed – it costs nothing to blind properly – and simply wasn’t a fair test.

Randomisation

Let’s take this out of the theoretical, and look at some of the trials which homeopaths quote to support their practice. I’ve got a bog-standard review of trials for homeopathic arnica by Professor Edward Ernst in front of me, which we can go through for examples. We should be absolutely clear that the inadequacies here are not unique, I do not imply malice, and I am not being mean. What we are doing is simply what medics and academics do when they appraise evidence.

So, Hildebrandt et al . (as they say in academia) looked at forty-two women taking homeopathic arnica for delayed-onset muscle soreness, and found it performed better than placebo. At first glance this seems to be a pretty plausible study, but if you look closer, you can see there was no ‘randomisation’ described. Randomisation is another basic concept in clinical trials. We randomly assign patients to the placebo sugar pill group or the homeopathy sugar pill group, because otherwise there is a risk that the doctor or homeopath – consciously or unconsciously – will put patients who they think might do well into the homeopathy group, and the no-hopers into the placebo group, thus rigging the results.

Randomisation is not a new idea. It was first proposed in the seventeenth century by John Baptista van Helmont, a Belgian radical who challenged the academics of his day to test their treatments like blood-letting and purging (based on ‘theory’) against his own, which he said were based more on clinical experience: ‘Let us take out of the hospitals, out of the Camps, or from elsewhere, two hundred, or five hundred poor People, that have Fevers, Pleurisies, etc. Let us divide them into half, let us cast lots, that one half of them may fall to my share, and the other to yours … We shall see how many funerals both of us shall have.’

It’s rare to find an experimenter so careless that they’ve not randomised the patients at all, even in the world of CAM. But it’s surprisingly common to find trials where the method of randomisation is inadequate: they look plausible at first glance, but on closer examination we can see that the experimenters have simply gone through a kind of theatre, as if they were randomising the patients, but still leaving room for them to influence, consciously or unconsciously, which group each patient goes into.

In some inept trials, in all areas of medicine, patients are ‘randomised’ into the treatment or placebo group by the order in which they are recruited onto the study – the first patient in gets the real treatment, the second gets the placebo, the third the real treatment, the fourth the placebo, and so on. This sounds fair enough, but in fact it’s a glaring hole that opens your trial up to possible systematic bias.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Bad Science»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Bad Science» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Bad Science» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Роман Зыков - Роман с Data Science. Как монетизировать большие данные [litres]](/books/438007/roman-zykov-roman-s-data-science-kak-monetizirova-thumb.webp)