Nir Rosen - Aftermath

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nir Rosen - Aftermath» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Nation Books, Жанр: Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Aftermath

- Автор:

- Издательство:Nation Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-786-72758-2

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Aftermath: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Aftermath»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

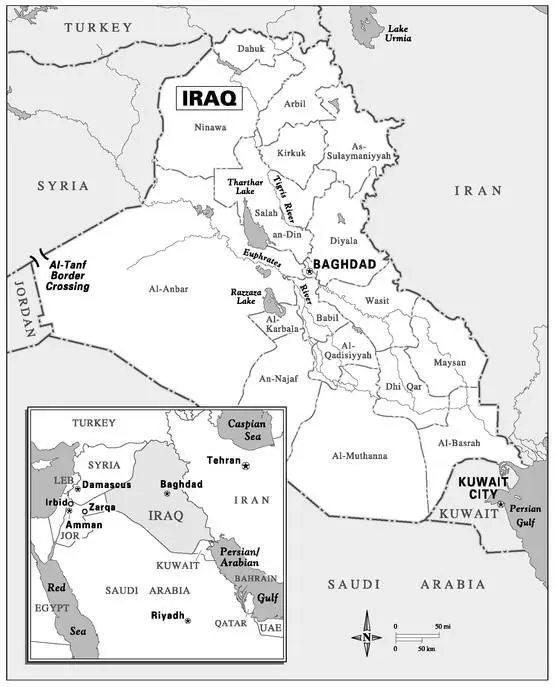

, an extraordinary feat of reporting, follows the contagious spread of radicalism and sectarian violence that the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the ensuing civil war have unleashed in the Muslim world.

Rosen—who the

once bitterly complained has “great access to the Baathists and jihadists who make up the Iraqi insurgency”— has spent nearly a decade among warriors and militants who have been challenging American power in the Muslim world. In

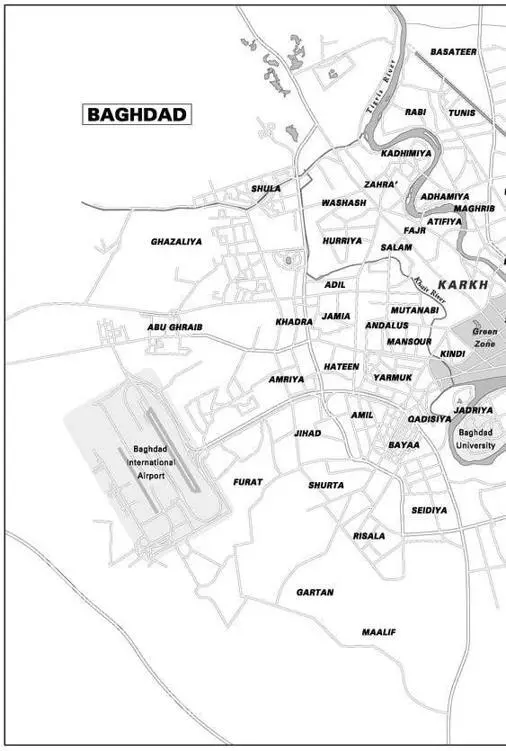

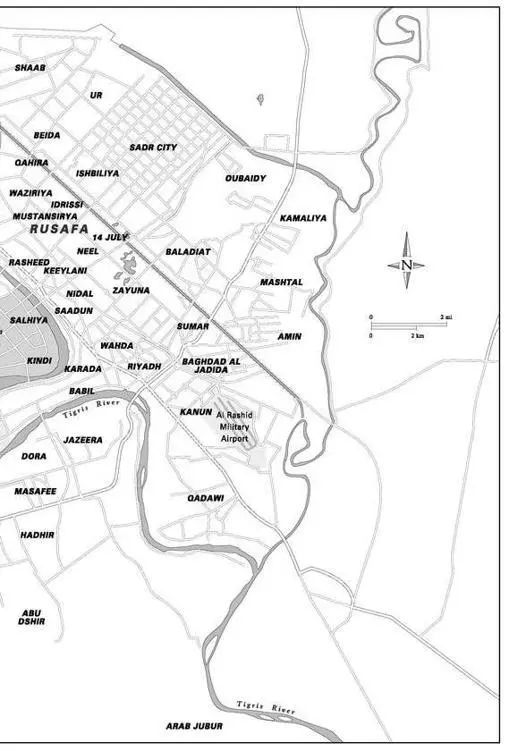

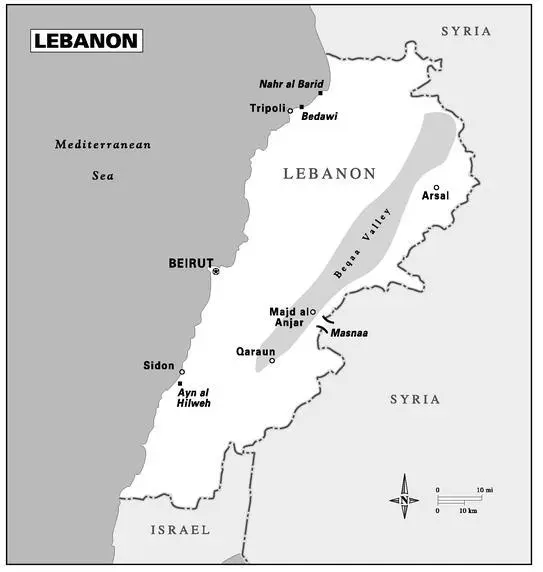

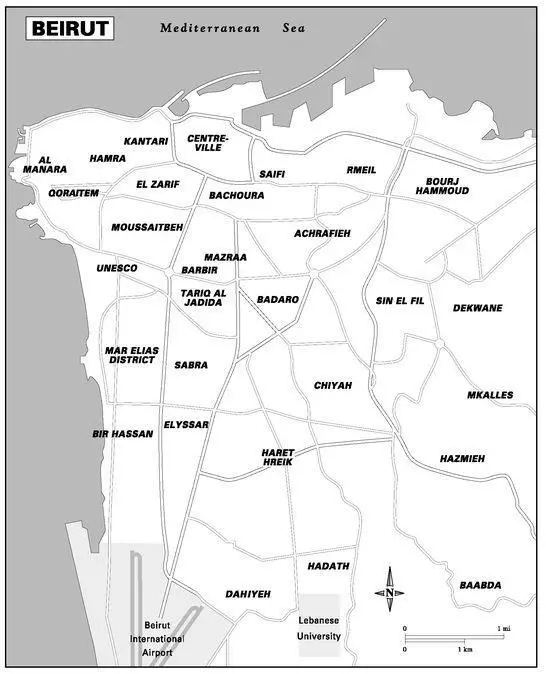

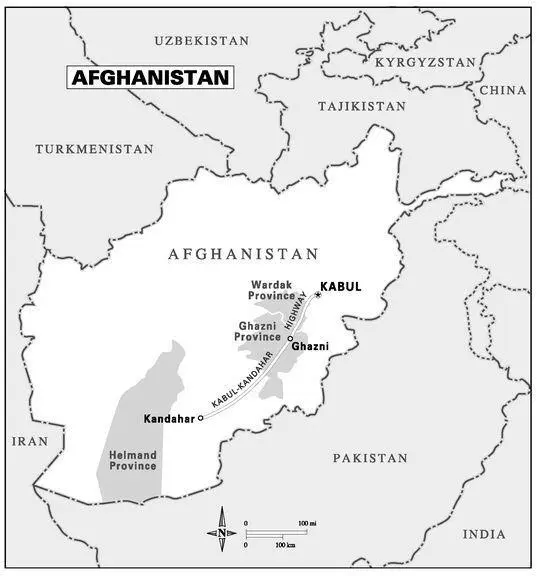

, he tells their story, showing the other side of the U.S. war on terror, traveling from the battle-scarred streets of Baghdad to the alleys, villages, refugee camps, mosques, and killing grounds of Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, and finally Afghanistan, where Rosen has a terrifying encounter with the Taliban as their “guest,” and witnesses the new Obama surge fizzling in southern Afghanistan.

Rosen was one of the few Westerners to venture inside the mosques of Baghdad to witness the first stirrings of sectarian hatred in the months after the U.S. invasion. He shows how weapons, tactics, and sectarian ideas from the civil war in Iraq penetrated neighboring countries and threatened their stability, especially Lebanon and Jordan, where new jihadist groups mushroomed. Moreover, he shows that the spread of violence at the street level is often the consequence of specific policies hatched in Washington, D.C. Rosen offers a seminal and provocative account of the surge, told from the perspective of U.S. troops on the ground, the Iraqi security forces, Shiite militias and Sunni insurgents that were both allies and adversaries. He also tells the story of what happened to these militias once they outlived their usefulness to the Americans.

Aftermath

From Booklist

This could not be a more timely or trenchant examination of the repercussions of the U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journalist Rosen has written for

, the

, and Harper’s, among other publications, and authored

(2006). His on-the-ground experience in the Middle East has given him the extensive contact network and deep knowledge—advantages that have evaded many, stymied by the great dangers and logistical nightmares of reporting from Iraq and Afghanistan. This work is based on seven years of reporting focused on how U.S. involvement in Iraq set off a continuing chain of unintended consequences, especially the spread of radicalism and violence in the Middle East. Rosen offers a balanced answer to the abiding question of whether our involvement was worth it. Many of his points have been made by others, but Rosen’s accounts of his own reactions to what he’s witnessed and how he tracked down his stories are absolutely spellbinding.

— Connie Fletcher