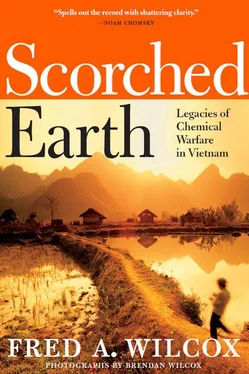

Some years after the last official American spray mission in the Central Highlands, the children’s father served with the army in that region. He recalls once when many men in his unit began choking, and became so ill that they had to be medivaced to a hospital. Pham Xong also served in Cambodia, close to the border of Vietnam, an area that was heavily sprayed with defoliants. Skeptics might argue that most of the dioxin in these regions had probably washed out of the soil; however, this does not take into account the fact that the half-life of dioxin on surface soil fluctuates between nine and twenty-five years, and in deeper levels from twenty-five to one hundred years.

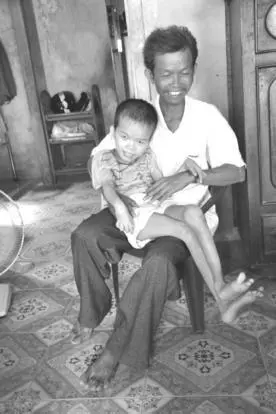

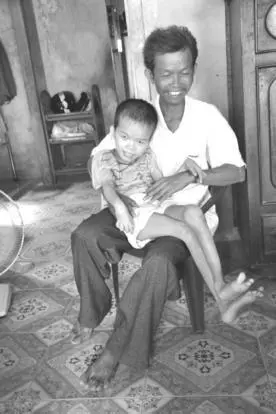

Father and son

According to Dr. Alan Schecter, one of the world’s experts on dioxin, “a person may be found with dioxin in his/her blood after 35 years of getting contaminated.” 1

Thirty-five years after the last spray mission in Vietnam, scientists have found astonishing levels—up to 1,000 times the permissible level in the United States—of dioxin at former military bases like Bien Hoa, Danang. There are no reliable studies of how many people living near these bases may have been heavily exposed to dioxin, or what the future consequences for these people and their offspring might be. It is clear that dioxin has entered the food supply of people who live near bases from which the Air Force flew thousands of defoliation missions.

In 1967, Arthur W. Galston, a renowned professor of Botany at Yale University, tried to warn the US against the continued, unbridled use of herbicides in Vietnam:

“We are too ignorant of the interplay of forces in ecological problems to know how far-reaching and how lasting will be the changes in ecology brought about by the widespread spraying of herbicides. The changes may include immediate harm to people in sprayed areas.” 2

Galston’s warning turned out to be prophetic. Just two years later, reports of birth defects in the offspring of Vietnamese women began to appear in Saigon newspapers.

At the New York Temporary Commission on Dioxin Exposure hearings in 1981, a Vietnam veteran testified that “before my son was ten and a half months old, he had to have two operations because he had bilateral inguinal hernia, which means his scrotum didn’t close, and his intestine was where his scrotum was, and his scrotum was the size of a grapefruit. He also has deformed feet… My oldest daughter has a heart murmur and a bad heart. Once she becomes active, you can see her heart beat through her chest as though the chest cavity is not even there, as though you were looking at the heart.” 3

At the same hearings, a Vietnam veteran’s wife testified that she was married to a Vietnam veteran who was in combat in 1967 and 1968.

“We have two sons,” she said, “a four-year-old and one who is four months. Our first son was born with his bladder on the outside of the body, a sprung pelvis, a double hernia, a split penis, and perforated anus.

“We have met other veterans,” she continued, “and their families. We have met their children. We have seen and heard about the deformities, limb and bone deformities, heart defects, dwarfism, and other diseases for which there is no diagnosis…. There are hundreds of children with basically the same problem, but in groups; so many bifidas, so many bone deformities, urological, neurological. But it is in groups of hundreds, not ones or twos.” 4

In a study, “Genetic Damage In New Zealand Vietnam War Veterans,” Louise Edwards writes:

Tuyet and Johansson (2001) conducted a study on Vietnamese women and their husbands who were exposed to Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. The authors found that 66 percent of all children had some type of major health problem. Thirty-seven percent of these children were born with some visible malformation or disability while 27 percent had developed a disability during the first year of life. Of the 60 children suffering from health problems, 40 were unable to attend school but were able to help with agricultural work and domestic chores. Twenty children were disabled very severely physically and mentally, and required 24-hour care needing to be attended to by their parents for every need. There were no cases of congenital malformation nor other disabilities among unexposed siblings of the husbands and wives, nor among the children of their siblings. 5

Addressing the concerns of New Zealand veterans who worried about the effects of Agent Orange/dioxin on their own children and future generations, the report stated:

The results from the SCE study show a highly significant difference between the mean of the experimental group and the mean of the control group (p < 0.001.) This result suggests, within the strictures of interpreting the SCE assay, that this particular group of New Zealand Vietnam War veterans has been exposed to a harmful substance(s) which can cause genetic damage. Comparison with a matched control group would suggest that this can be attributed to their service in Vietnam. The result is strong and indicates that further scientific research on New Zealand Vietnam veterans is required. 6

Pham Xong and his wife realized early on that their daughter was suffering from serious birth defects; however, they hoped to have at least one child who could live a normal life and help them in their old age. Instead, their son could neither walk nor talk, had seizures, and would never outgrow his handicaps. That’s when they decided not to have any more children. They are aware that there is no cure for dioxin exposure, yet they do not blame anyone for their plight.

Preparing to leave, I hesitate, trying to think of something we might do to ease this family’s burden. It’s difficult to say goodbye to families like this one. We walk into their barren little houses, produce a tape recorder, and ask painful questions. Then, we take photographs, and we leave an envelope containing 100,000 Dong, the equivalent of about $12, for which the recipients are genuinely grateful.

I could apologize for our government’s indifference to the plight of Agent Orange victims, but that feels rather self-indulgent, and might embarrass this gentle family. I could promise to return with a shaman who will give their son the power of speech and their daughter the ability to walk, but I don’t know anyone who possesses powers like that. The families we visit will never sit in an air-conditioned theater, munching buttered popcorn while beautiful actors make them feel happy and frightened and safe and wonderfully sad. They won’t join friends in a cheerful restaurant, drinking wine and eating until they’re pleasantly stuffed. Their children will not spend hours talking on a cell phone, planning weekend parties, being young and strong and full of optimism.

All we can do is promise that we will tell people about the extraordinary families we meet, the beautiful children, the determination, the courage, and the terrible suffering we encounter in Vietnam. We must hope, as the Vietnamese do, that this will be the last generation of children to suffer from the effects of chemical warfare.

Pham Xong and his wife pose with their children for photographs as a loving family, which they most certainly are.

During the monsoon rains last year, water poured into this tiny house, climbing so high (water marks on their green walls) that the family was in peril of drowning. A charitable organization will build the family a balcony, so that when the rains flood their living room this year, they won’t die.

A myth has been created by the chemical companies that the US government somehow designed Agent Orange and that this was a special, unique chemical. IS NOT TRUE.

Читать дальше