Judge Weinstein concludes that:

The United States did not use herbicides in Vietnam with the specific intent to destroy any group. Nor were those herbicides designed to harm individuals or to starve a whole population into submission or death. The herbicides were primarily applied to plants in order to protect troops against ambush, not to destroy people. 30

And, in discussing the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which:

Prohibits the use in war of Asphyxiating Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Method of Warfare, June 17, 1925.

Judge Weinstein argues that:

The United States had not signed onto this agreement. Did sign in 1975. Included a caveat that if an “enemy state” or its “allies” fails to respect the Protocol, then the US will no longer be bound by its rules. Scholars disagree on what the Geneva Protocol means, or does not mean. Unlike the poisonous gases outlawed in the Geneva Protocol, herbicides were not designed to disable or kill human beings.” 31

Judge Weinstein, a brilliant legal scholar and an honorable man, ruled against US veterans and Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange on the basis of what he believed to be objective interpretations of national and international law. The appellate courts agreed with his decisions, and on February 27, 2009, the Supreme Court refused—without comment—to hear arguments on behalf of Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange.

In Vietnam, community workers say they need at least 1,000 new community organizations, known as “Peace Villages”—currently, they have twelve—to accommodate children who are suffering from the effects of chemical warfare. Throughout Vietnam, poverty-stricken parents struggle to take care of handicapped and seriously deformed children. They do not express anger, hatred, or blame. Holding boys and girls who cannot sit up on their own, mothers massage their children’s arms and legs, brush their hair, and welcome visitors who are there to offer their support and to witness the effects of toxic chemicals on human beings.

According to lawyers for the chemical companies: “the United States owes no duty in tort to enemy combatants, or even to noncombatants in a war zone. Imposing such a duty on the Government’s contractors would undermine the principle, obligating the United States to heed rules of civil conduct that can have no application in the theater of war…. Entertaining Plaintiffs’ challenge to those decisions [military decisions made by the president as commander-in-chief of the armed forces] would risk a stark lack of respect for the Executive Branch and risk multifarious and inconsistent pronouncements by various departments of government.” 32

Furthermore, say the chemical companies, the courts have no right to interfere with the commander-in-chief’s decisions during wartime.

No one knows, or will ever know, exactly how many American and Vietnamese citizens have died from exposure to dioxin since Victor Yannacone filed the Agent Orange product liability class action lawsuit in 1978. There is no count of the number of miscarriages and stillbirths Vietnamese and American women married to veterans have experienced in the past thirty-five years. The United States has no idea how many American children born with serious birth defects have fathers or mothers who served in Vietnam. No one will ever know how many American, Korean, Australian, New Zealand, and Vietnamese veterans have died from cancer and other Agent Orange related diseases since the war ended.

The Agent Orange tragedy has become a rather elaborate game of “you get your lawyer, I’ll get mine,” and “You get your scientist, I’ll get mine.” I’m not suggesting that all of the actors in this decades-long drama are nefarious characters or indifferent to human suffering. But I have to wonder what Thomas Jefferson and other founding fathers might have to say about the chemical companies’ arguments that the United States of America does not have to “heed the rules of civil conduct that can have no application in the theater of war.”

That the United States “owes no duty in tort to enemy combatants or even to noncombatants in a war zone.”

That the plaintiffs in the Vietnamese class action suit must not be allowed to question military decisions “made by the President as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.”

And that the courts have no right to interfere with decisions the commander-in-chief makes in wartime.

Does this mean that the president can initiate a campaign to bomb another nation, as Lyndon B aines Johnson did in 1964, based upon fabrications and lies? Can the United States attack another nation, using chemical weapons against its environment and its people for years, without being held responsible for maiming, starving, and killing noncombatants? Would questioning the commander-in-chief’s right to make military decisions that will result in the deaths of millions of innocent civilians indicate a lack of respect for the executive branch?

Lawyers for the chemical companies seem to be saying that when the president is acting as the commander-in-chief, he turns into a king. Would Jefferson agree?

CHAPTER 8

The Last Family

Occasionally I saw these [genetically deformed] children in contaminated villages in the Mekong Delta; and whenever I asked about them, people pointed to the sky; one man scratched in the dust a good likeness of a bulbous C–130 aircraft, spraying.

—John Pilger

On the outskirts of the city of Danang, women in conical hats tend rice paddies, bending in calf-deep water to plant new shoots. Brown cows and steel-gray water buffalo graze this ancient landscape, at peace now after centuries of invasions, uprisings, and war. We cross a narrow bridge, turn into a dirt road, and walk a short distance to a small, remarkably barren house, its walls scarred by monsoon flooding, and only the most rudimentary furniture—a low glass-covered wooden table, small red plastic chairs, no television or family shrine. It is the kind of home that one might find in the most destitute areas of Appalachia or on impoverished Indian reservations.

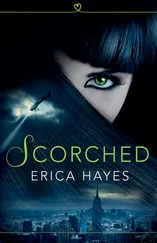

Nguyen Thi May sits on the floor, a twelve-year-old boy sprawled on her lap; her sixteen-year-old daughter, Trinh, leans close by her side. Until a recent operation on her legs, paid for by World Vision Vietnam, Trinh could not walk; now, her mother explains, she can move about “a little.” The girl’s skin is wrinkled and dry, like bark that might just peel away when touched, or catch fire in the Vietnam heat—we would later see a boy with this same condition, called x-linked ichthyosis, at a hospital in Ho Chi Minh City. When her mother bathes her, Trinh’s skin peels off, turns white, and then darkens like red wine. Trinh will never attend school or learn to care for herself, and while she smiles and waves one hand at her visitors, most of the time she stares about the room, expressionless.

Nguyen Thi May and her children

Nguyen Thi May’s husband, Pham Xong, confides that his son’s head is growing larger, while the boy’s body remains the same. Twelve-year-old Phan Van Truc suffers from seizures, and his parents say they never know when they might occur. He cannot speak or walk, he requires constant attention, and he will never get any better. His father worries that the boy appears to be getting weaker, a condition that defies explanation.

The children seem happy to see students from SUNY Brockport’s study abroad program, and when Brendan takes photographs of the boy sitting on his father’s lap, he grins and wiggles his feet. Pham Xong and Nguyen Thi May do not own a motorbike, and they move their children about on a rough-hewn wooden cart. One parent must be at home at all times, making it difficult for the family to earn money. Doctors have examined these children and determined that their birth defects are symptomatic of exposure to dioxin, but there are no funds available to examine the father’s sperm, blood, or fatty tissue. Pham Xong is forty-seven years old; his wife is forty-two, young enough, when their children were conceived, to have given birth to healthy offspring.

Читать дальше