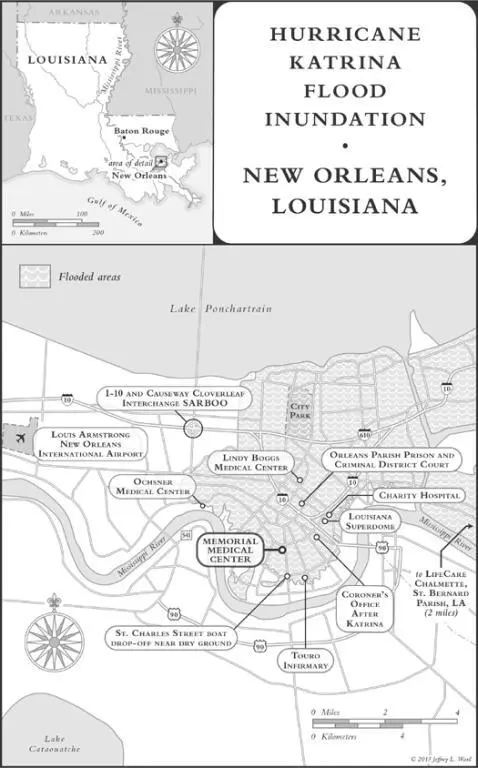

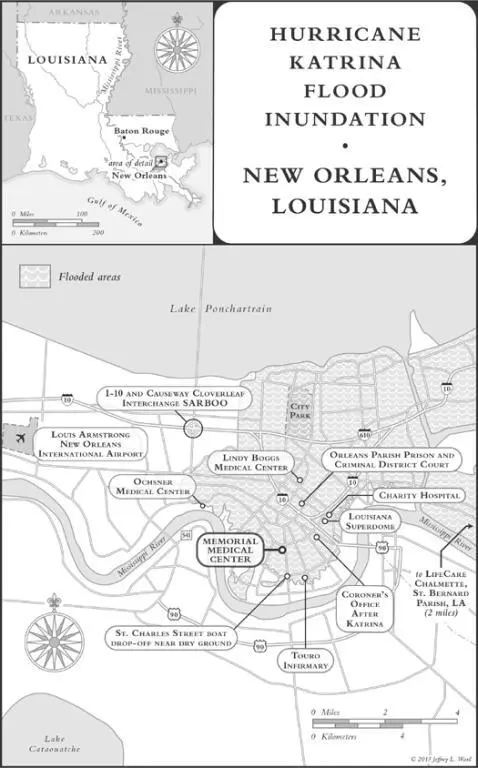

In the late morning, she had gone downstairs to Memorial’s incident command leaders, provided a list of LifeCare’s most critical patients, and told them that LifeCare was trying to do whatever was possible to move its own patients. An Acadian ambulance paramedic on-site at Memorial registered surprise that LifeCare was awaiting direction from corporate officials, as he believed Acadian had a transportation contract with LifeCare, and he wanted to help them.

In the command center, Memorial’s leaders informed Robichaux that the helipad was operational and LifeCare could land helicopters on it. Robichaux came back upstairs and shared the news via the chat connection with a corporate contact in Shreveport, Robbye Dubois, LifeCare’s senior vice president for clinical services. Robichaux sent Dubois a list of fifty-three LifeCare patients who needed to leave Memorial (two of the original fifty-five had died). Most critically, seven relied on ventilators, one on an assisted-breathing device, and five needed dialysis.

The reply from Shreveport appeared letter by letter on the screen, tracking backward, excruciatingly, whenever a typed mistake was corrected. Shreveport employees were in contact with a man named Knox Andress, who, they believed, worked with FEMA in Baton Rouge. He’d said FEMA and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals were aware of LifeCare’s situation and planned to evacuate patients on ventilators first. Because all of the hospitals needed help, he could not tell them when, exactly, the cavalry would arrive.

They waited. An employee in Shreveport offered to make calls for LifeCare staff members in New Orleans who wanted to let their families know they were OK. Some had been unable to contact loved ones for almost two days. Phone numbers and messages were passed on the chat connection: “Yvette is alive, love you guys”; “I’m alright cant reach you, tell Marvin that I love him.”

Then, in the midafternoon, came an urgent offer from Memorial, followed by confusion. LifeCare patients could go out on the Coast Guard helicopters heading for Baton Rouge. LifeCare had twenty minutes to decide whether to send patients this way.

Before they could answer, the offer was withdrawn. The Memorial representative had assumed that LifeCare’s patients were included in the patient count sent to the Coast Guard, but it wasn’t true. When Memorial incident commander Susan Mulderick had reached an air evacuation coordinator at the Coast Guard’s emergency command center in Alexandria, Louisiana, by phone in the early afternoon, he had logged her request to transport two hundred people—just slightly more than the number of Memorial patients. “LifeCare patients were not included. Repeat NOT included,” Robichaux typed to her Shreveport colleagues.

Memorial, Robichaux wrote, had worked on the assumption that FEMA was coordinating LifeCare’s transport, an understanding that seemed to have stemmed, like in a game of telephone, from the conversation between LifeCare’s Shreveport representatives and Andress, the man they believed worked with FEMA. Only, as they would find out much later, Knox Andress was a nurse at a Catholic hospital in Shreveport who had volunteered as a hospital disaster-preparedness coordinator for his region of northwest Louisiana after 9/11. His volunteer title, “HRSA District Regional Coordinator,” was based on the federal hospital bioterrorism preparedness grant to the state. He displayed it proudly on his CV, and he took his role very seriously, participating in local and national training programs as a student and speaker. He did not, however, work for FEMA.

The most important message was this: “MMC told us that they are going first. First the critical then the other patients.” That meant even Memorial’s less sick patients were being prioritized over LifeCare’s generally very sick ones.

Robbye Dubois, in Shreveport, said that she thought the helicopters heading to Memorial were coming for both Memorial and LifeCare patients. “We have spoken to the folks at FEMA and we were supposed to be included in the move.” It was hard to imagine that FEMA and the Coast Guard wouldn’t be coordinating with each other. Besides, these were federal resources. How could Memorial monopolize them? If the goal was to get the critically ill patients out first, then why should Memorial’s noncritical patients go out before LifeCare’s critical ones?

At around five p.m., Robichaux spoke with the LifeCare New Orleans administrator who had evacuated with his family. She told him Tenet’s patients were being lined up for evacuation, which was a little depressing for the LifeCare staff. From the pharmacy computer on the hospital’s seventh floor, Robichaux also pressed her colleagues in Shreveport for specifics. Had FEMA actually said that the Coast Guard airlift at Memorial could include LifeCare?

A LifeCare staff member in Shreveport called Knox Andress again to check. “All he is telling me is that they have our information and will get back to us,” she wrote to Robichaux. “I specifically asked several times if we were to be included with MMC and all I got is they have our information and will be evacuating all hospitals.” The hospitals were, Andress had told her, going to be evacuated in a certain order, though it was unclear what that order would be.

Corporate Senior Vice President Robbye Dubois would keep making calls from Shreveport, trying to reach whomever she could who might help. “Please keep pushing from your end,” she wrote to Robichaux, urging her to go to the helipad and explain to the Coast Guard that LifeCare was a hospital within Memorial and also needed to be evacuated.

Dubois was working at a disadvantage. LifeCare had employed her for many years, and she commuted between its corporate headquarters in Plano, Texas, and her home two hundred miles away in Shreveport, where she was now, working out of a hospital. But her superiors were new, part of a management team appointed by the investment firm The Carlyle Group, which had acquired LifeCare earlier in the month. Most of them, including her new boss, LifeCare’s corporate COO, happened to be traveling and out of the office that day.

Dubois was not inclined to turn to her new boss for help in any case. The morning before Katrina struck, he had questioned whether evacuating the Chalmette campus of LifeCare alone was doing enough given the strength of the coming storm. He wanted suggestions on what might be done to help the other two New Orleans–area campuses after the hurricane hit, such as bringing in additional staff from Shreveport or Dallas to help. Dubois had sent him a terse reply. Hospital evacuations weren’t being recommended, the campuses were well staffed and supplied, and she had compiled a list of staff who could go to New Orleans from Shreveport.

Now, as conditions deteriorated, there was no way she was going to bring more LifeCare staff into danger to relieve the exhausted staff, which was what she believed her superiors wanted. When she floated the idea of hiring buses to aid in the evacuation, they did not seem enthusiastic. She decided to head up the corporate disaster response alone, assisted mainly by a LifeCare quality management director and an information technology specialist with her at the hospital in Shreveport. She would do whatever it took to aid these hospitals, to the best of her abilities, and ask permission later. She did not turn to higher-ups at the multibillion-dollar firm, who might have had more influence or resources at their disposal, because she felt she wouldn’t get help from them.

Back in New Orleans, Diane Robichaux went downstairs to Memorial’s command center. When she returned, she seemed to have accepted the status quo out of a sense that LifeCare was covered by at least one of the federal agencies. “OK got clarification again,” she wrote. A Memorial representative said the hospital was not using FEMA to evacuate its patients. It was using the Coast Guard to get patients to Baton Rouge on the way to other Tenet facilities.

Читать дальше