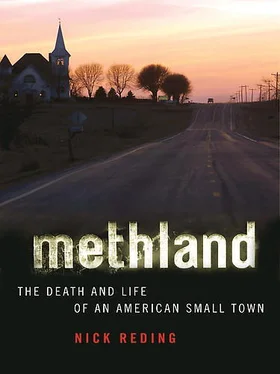

So, too, had there been by 2005 thousands of stories across the country blaming meth for delusional violence, morbid depravity, extreme sexual perversion, and an almost otherworldly, hallucinogenic dimension of evil. In 2004, an Ojibwa Indian named Travis Holappa in Embarrass, Minnesota, had been tied to a chair in a rural swamp, tortured, shot eleven times, and then decapitated after running afoul of meth dealers. In a suburb north of Atlanta, in the space of one week that same year, thirteen bodies were found, bound and murdered execution-style in a single home used as a meth stash house. In Ottumwa, Iowa, a ten-year-old girl’s stepfather was jailed for his habit of getting high on crank and then repeatedly forcing the girl, at gunpoint, to perform oral sex on him, an act that he justified, in his hallucinogenic, psychotic state, by saying to police that the girl was the devil and that she had begged him to do it. In Oelwein, in June of 2005, a man high on meth beat another with a glass vase, and thinking he was dead, rolled him in a blanket, then shoved his body behind the couch, where his teenage daughter found him the next afternoon. And yet, methamphetamine was once heralded as the drug that would end the need for all others.

Nagayoshi Nagai, a Japanese chemist, first synthesized desomethamphetamine in 1898. Almost from the beginning, the drug was celebrated for the simple fact that it made people feel good. It was not, however, until Akira Ogata, another Japa nese chemist, first made meth in 1919 from red phosphorus and ephedrine, a naturally occurring plant that grows largely in China, that mass production of the drug became viable. Red phosphorus, the active ingredient on the striker plate of a matchbook, can be mined. Ephedrine, like coca or poppies, can be farmed. By 1933, meth was heralded in the United States as a drug on par with penicillin. In 1939, the pharmaceutical giant Smith, Kline, and French began marketing the drug under the name Benzedrine. In Japan, meth was sold as Hiropon; in Germany, it was marketed under the name Pervitin. In addition to narcolepsy and weight gain, methamphetamine in 1939 was prescribed as a treatment for thirty-three illnesses, including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, the common cold, hyperactivity, impotence, fatigue, and alcoholism. In a world in which the winners were defined by the speed with which they could industrialize, meth suppressed the need for sleep, food, and hydration, all the while keeping workers “peppy,” as the ads read. The miracle cure could even aid in the nightmare of war, once the industrializing nations of Germany, Britain, Japan, and the United States began fighting for world dominance.

According to a presentation given by former Harvard sociologist Patricia Case, reports authorized by the U.S. government in 1939 suggested that meth had “psychotic” and “anti social” side effects, including increased libido, sexual aggression, violence, hallucinations, dementia, bodily shaking, hyperthermia, sadomasochism, inability to orgasm, Satanic thoughts, general immorality, and chronic insomnia. Nonetheless, Japanese, American, British, and German soldiers were all given methamphetamine pills to stay awake, to stay focused, and to perform under the extreme duress of war. Methedrine, according to Case, was a part of every American airman’s preflight kit. Three enormous plants in Japan produced an estimated one billion Hiropon pills between 1938 and 1945. According to a 2005 article in the German online news source Spiegel , the German pharmaceutical companies Temmler and Knoll in only four months, between April and July 1940, manufactured thirty-five million methamphetamine tablets, all of which were shipped to the Nazi army and air corps. A January 1942 doctor’s report from Germany’s Eastern Front is illuminating. Five hundred German soldiers surrounded by the Red Army began trying to escape through waist-high snow, in temperatures of sixty degrees below zero. Soon, the doctor wrote, the men began lying on the snow, exhausted. The commanding officers then ordered their men to take their meth pills, at which point “the men began spontaneously reporting that they felt better. They began marching in an orderly fashion again, their spirits improved, and they became more alert.” In an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 1985, one of Hitler’s doctors, Ernst-Günther Schenck, revealed that the Führer “demanded interjections of invigorating and tranquilizing drugs,” including methamphetamine. It’s widely believed by many that Hitler’s subsequent and progressive Parkinson’s-like symptoms, if not his increasingly derelict mental state, were a direct result of his meth addiction.

Even into the 1980s, methamphetamine was widely prescribed in the United States. Ads for “Methedrine-brand Methamphetamine—For Those Who Eat Too Much and Those Who Are Depressed” appeared all during the 1960s, largely in women’s magazines. Obedrin Long-Acting, according to another ad, was there to help a woman “calmly set her appestat,” a particularly apt pun given that meth is well known to raise one’s body temperature to dangerously hyperthermic levels. In 1967 alone, according to Dr. Case, thirty-one million legal meth prescriptions were written in the United States. In Dexamyl ads in Life magazine throughout the 1970s, a woman wearing an apron could be seen ecstatically vacuuming her living room carpet. How much legal pharmaceutical methamphetamine was being sold illegally, or without a prescription, during the period from 1945 to 1975 is hard to imagine. Headlines from the New York Times circa 1959 give some indication, however, citing multicity FBI stings in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Phoenix, Denver, Indianapolis, Chicago, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Manhattan.

Curiously, the fate of towns like Oelwein, which for one hundred years had been places of great prosperity, began to change at just about the time that meth’s reputation began to disintegrate. Even as those towns started feeling the early effects of changes to the food-production industry, which would all but bankrupt them thirty years later, meth during the late 1970s and early ’80s was being illegally produced by bike gangs like the Hells Angels in California and the Sons of Silence in the Midwest. The change, which can be characterized by the shift from pharmacy to “lab,” is what would precipitate the modern American meth epidemic, itself only a large piece of the global meth pandemic. As Methedrine and Benzedrine became crank and speed, production moved from the controlled environment of corporate campuses to the underground production sites of bikers and outlaw chemists. The new form of meth, a drug that has always been popular among men and women doing hard labor, became both purer and vastly more available. It was no accident that just as rural economies were at the peak of their suffering in the mid-1980s, meth’s place in the United States was becoming more entrenched than ever.

Part of meth’s draw in U.S. small towns beginning in the 1980s is that it’s both cheap and easy to make from items available, in bulk, at the farmers’ co-op and the drugstore. The real basis of meth’s attractiveness, though, is much simpler: meth makes people feel good. Even as it helps people work hard, whether that means driving a truck or vacuuming the floor, meth contributes to a feeling that all will be okay, if not exuberantly so. By the 1980s, thanks to increasingly cheap and powerful meth, no longer was the theory behind the American work ethic strictly theoretical: there was a basis in one’s very biochemistry, a promise realized. And according to the magazine and newspaper ads, all of it came without any of the side effects which hardworking Americans loathe: sloth, fatigue, laziness.

In biochemical terms, methamphetamine is what is called an indirect catecholamine agonist, meaning that it blocks the reuptake of neurotransmitters. When you feel good, it’s because dopamine or epinephrine has been released into the synaptic gaps between the neurons in your brain. Metaphorically, this microscopic emission is a simulacrum at the tiniest, most ethereal level for the release and subsequent satiation one feels for having performed some kind of biologically essential task, such as having sex. Later, the neurotransmitter is soaked up out of the synapses, like water into a sponge, by the inverse neuronal process, one designed to be as efficient as it is perpetual. Indeed, running out of neurotransmitters, the feel-good chemicals that reward you for remaining biologically viable, would be tantamount to the nihilistic meaninglessness that Oelwein mayor Larry Murphy feared had engulfed his town by 2005.

Читать дальше