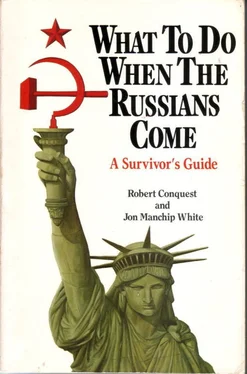

Robert Conquest - What to Do When the Russians Come

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Conquest - What to Do When the Russians Come» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1984, ISBN: 1984, Издательство: Stein and Day Inc., Жанр: Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What to Do When the Russians Come

- Автор:

- Издательство:Stein and Day Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:1984

- Город:New York

- ISBN:0-8128-2985-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What to Do When the Russians Come: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What to Do When the Russians Come»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What to Do When the Russians Come — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What to Do When the Russians Come», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

You will pick your targets with the greatest care. As far as possible, limit yourself to those related directly to the Russians. You will not help your fellow citizens if you make their already uncomfortable lives even more uncomfortable by destroying the power stations, dams, and other facilities on which they rely. If, for military or political reasons, it nevertheless seems necessary to carry out such actions, let the population know your reasons.

Never forget that they are liable to the most savage reprisals. Hostages will be taken and shot. You will have to judge the merits of an operation against the horrors that are bound to result. It will astonish you, at first, how remorselessly the Russians will behave—not only toward yourself, but toward your families, toward anyone brave enough to help you, and also toward the populace at large. They have always done so, and now there will be little or no world opinion to influence what is going on. The Russians can act as they like: that is to say, as they acted in Lithuania and the Western Ukraine and as they are now acting in Afghanistan, or worse. Their ultimate argument was, and remains, the tank and the firing squad.

Nevertheless, even in cases where the prospects are poor, where the Russians can hunt you down in your forests, starve you out in your swamps, and bottle you up in your canyons, you will remember that elsewhere groups are holding out, fighting back; that you are part of a great national effort.

You will have advantages over your comrades in the cities. You will be able to operate your radios fairly freely; you might possibly be able to arrange for supplies to be smuggled in from abroad. Yet yours will not be an easy lot. The vast landscape in which you feel at home will sometimes seem to have turned into a prison. You will become more and more hardened physically and psychologically; yet your strength will also be sapped by the climate, whether hot or cold, wet or dry. You will have difficulties with food supplies. The winters will be hard.

All the same, hold out. Do not at any time be tempted to parley with the Russians under a flag of truce. In 1945, the Polish underground leaders contacted the Russians. They were guaranteed safe-conduct but were immediately arrested and later tried and sentenced for anti-Soviet activity. In 1956, the Hungarian minister of war was induced to attend talks with the Red Army commander in Hungary. He too was arrested, tried, and hanged. American partisan chiefs are likely to get an even shorter shrift, so do not weaken. It seems a more enviable fate to die fighting on Pike’s Peak than in a cellar in Pittsburgh.

Partisans, generally speaking, cannot hold out forever unless they are aided from outside. Nevertheless, it has often taken a number of years even for the Communists, totally uninhibited as to methods, to destroy guerrilla movements even in comparatively small areas. The Lithuanian partisan struggle, in a small, well-forested but nonmountainous territory, was not abandoned till eight years had gone by. The same applies to the western Ukrainian partisans, in the more mountainous regions of the north Carpathians. In the larger territories of America, a longer struggle could probably be sustained, even though we may set against this the advantages of new Russian equipment.

It may be improbable that the Soviet system could be shaken to the point of collapse in so short a period. But nothing is impossible, and in the case of mass risings throughout the Soviet empire, American partisans could play a big part. In the more likely event that partisan warfare becomes ineffective long before the Soviet grip is shaken, it may be better for the partisan command to make a conscious decision to demobilize their surviving fighters, providing them with false papers and cover stories and fitting them into properly chosen backgrounds—as in both Lithuania and the Ukraine.

By that time, survivors would be few. If you are among them, you will act out the life of a loyal Soviet-American citizen and await your time. It may not come in your lifetime, but you can go to your grave with a clear conscience.

Good luck!

In the cities, and other areas easier to control than the mountains and forests, armed resistance will be difficult. For a few months, “urban guerrillas” in very small groups may succeed in carrying out sporadic acts of assassination and sabotage against the occupiers. But such groups have never succeeded in maintaining themselves for long in Communist-occupied countries. It may be that, in the special circumstances of America, such groups will last longer. But in a comparatively short time, at any rate, the complete ruthlessness of Communist secret police methods, involving in each case the probable arrest and torture of hundreds of people who might conceivably know anything, will probably have its effect. The illegal possession of a weapon will, in itself, in the early stages, carry the death penalty and, even later, will always involve sentencing to a labor camp even in the absence of any suspicion of rebellious intent.

Nevertheless, there will be Americans who feel impelled to strike back in this way. And, in spite of the disadvantages, some good results may yet be attained. Our advice is: Do not waste your efforts. A single, really massive act of sabotage against a carefully picked secret police or military target may be worthwhile; wrecking the odd train will not. The assassination of local, and if possible, of more important Quislings is also worthwhile, both in cheering the population and frightening the rulers.

After a few years, though, armed resistance in the cities on any organized basis will be virtually extinct. The resentments of the American people will not.

In fact, in all the countries that have come under Soviet occupation, the population has never become reconciled to the regime. The rulers have maintained support only from that small caste that has done well in terms of power and privilege and from a limited gang of indoctrinated young thugs. The sheer pervasiveness and ruthlessness of the secret police and the whole power apparatus is enormous. But only armed force, including the Soviet army itself and the prospect not merely of defeat but of greatly intensified military terror, has kept the people down.

Even so, time after time, whole populations have come together in great movements of resistance and rebellion that have at least temporarily thrown off the Soviet yoke.

Among Americans, with their special attachment to the principles of liberty, their special horror of foreign rule, you may expect that Communist control will never even begin to strike serious roots. People will be cowed, baffled, disorganized. Some may even hope to work “within” the new system and turn it in a more acceptable direction. But the invariable experience has been that Communist policies increasingly antagonize every section of the population—including major sections of the Party itself, who see that they cannot rule indefinitely on such a basis.

Even in democracies, governments become unpopular. And they would become even more unpopular if they stayed in power, even without terror, for a decade or decades. How much more is this true of an unpopular foreign-sponsored clique, bound by its principles to ever more hated and unsuccessful policies. A poll taken in Czechoslovakia at the end of 1967 showed that the then leaders of the Party and State had the support of 1 percent of the population.

The situation that will thus be established, throughout the Soviet empire, is that of a population faced with a political and military machinery developed over many years for the purpose of holding down resentment and preventing its expression. And of crushing it if, in spite of everything, it turns into full rebellion.

Yet as the years go by, you will sooner or later find yourself swept up in a mass movement against the occupier. These movements are very often started in the cities, in the form of strikes and demonstrations by the industrial workers (see p. 95). With no trade union rights, yet thrown closely together by the nature of their work, they are the first to be able to make some united protest at a reduction in the rations (or mere absence of necessary foods in the market), at deteriorating housing conditions, or sudden cuts in piece-rates—all of which have always, sooner or later, appeared in cities under Communist regimes. This is not, of course, the only way in which pent-up resentments will be released; some gross offense to national pride has also been the last straw in bringing people out onto the streets. In any case, after years of repression, during which you may have felt that no one else thought as you did, it will be immensely refreshing to find the bulk of the population coming together as comrades in a struggle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What to Do When the Russians Come»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What to Do When the Russians Come» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What to Do When the Russians Come» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.