This quintet of authors gathered to sketch the range of destinations where the world may be headed. We have summarized and refocused on the future many arguments from our previously written volumes. Intentionally, this is not a single-tune quintet. The hope was to achieve counterpoint and provoke each other into pursuing the implications of our individual themes. We have included the complexities, caveats, and dissents. We have not avoided the dramatic, even thunderous notes. Such tonalities seemed warranted by the enormity and gravity of the main themes. The coming decades will be anything but usual: that is, usual in the perspective of the last 500 years. The collective trajectory of humanity is taking a big turn, but not necessarily for the worse.

A rising note of optimism emerges in the finale. A big crisis and transformation, whatever its scenario, does not mean the world is coming to an end. There is no reason to believe, on the basis of the accumulated understandings of sociology, that history will ever end, as long as there are human beings connected in social organization. The direst scenarios involving a world nuclear war or environmental collapse, fortunately, seem avoidable precisely because collective extinction has been widely regarded as a real danger for some decades now. The end of capitalism is not a catastrophe of that sort. A crisis in the bearing structures of the modern world’s political economy is far from a doomsday prediction. Ultimately, the end of capitalism is a hopeful vision. Yes, it comes with its own dangers. We must remember how early twentieth-century attempts to foster anticapitalist alternatives in response to crisis developed totalitarian tendencies and ended in bureaucratic inertia. Nor should we forget how directly these anticapitalist projects arose from the state machineries and personnel constructed in the world wars. The crucial political vectors in the coming decades will have to be curbing militarism and institutionalizing democratic human rights around the planet. An impasse in the political economy of capitalism brings us to historical junctures where what has been long regarded utopian may yet acquire technically feasible foundations in a new kind of political economy. It may yet help us to deal better with threats to our planet’s biosphere, and many other tasks that humanity will be facing later in this century.

Those who worry about postcapitalism ushering in a period of deadly stagnation are surely wrong. Those who hope that postcapitalism will deliver a lasting paradise without its own crises are likely wrong, too. After the crisis—and, some of us predict, the postcapitalist transition of the mid-21st century—there will be a great deal happening. Hopefully, much of it will be good. We shall see, and soon enough.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

© Oxford University Press 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice, 1930–

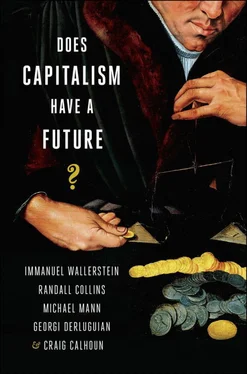

Does capitalism have a future? / By Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian and Craig Calhoun.

p. cm.

ISBN 978–0–19–933084–3 (hardback) — ISBN 978–0–19–933085–0 (paperback)

1. Capitalism. 2. Middle class. 3. Technological innovations—Forecasting. I. Wallerstein, Immanuel. II. Title.

HB501.W2935 2013

330.12’2—dc23

2013018969

9780199330843

9780199330850 (pbk.)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Prigogine, The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature (New York: Free Press, 1996), 166.

I explain this process in “The Concept of Hegemony in a World-Economy,” in Prologue to the 2011 Edition of The Modern World-System, II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750 (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2011), xxii–xxvii.

It is true that the “Marxists” divided into two camps as of the Russian Revolution, the Social Democrats (or 2nd International) and the Communists (or 3rd International). However, their differences were not about the two-step strategy, but rather about how to achieve the first step—taking state power. Furthermore, by 1968, the Social Democrats had stopped calling themselves Marxists, while the Communists were now calling themselves Marxist-Leninists. For the young persons who made up the bulk of the participants in the world-revolution of 1968, this debate between the adherents of the two Internationals, so important to the Old Left, seemed almost irrelevant, as these young persons tended to have disparaging opinions about both varieties of Old Left social movements.

One has to remember that, at that time, the principal policy of the Social Democratic parties—the welfare state—was accepted by their conservative alternate parties, which merely quibbled about the details. I consider New Deal liberals in the United States to be a variety of Social Democrats who simply declined to utilize the label for reasons peculiar to the political history of the United States.

Most Latin American countries had become formally independent in the first half of the nineteenth century. But populist movements there showed analogous strength to national liberation movements in the still formally colonial world.

I discuss them much more intensively in the last two volumes of my The Sources of Social Power : The Great Depression in Volume 3, Chapter 7, and Volume 4, Chapter 11: Global Empires and Revolution, 1890–1945 . (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), and the Great Recession in Volume 4: Globalizations, 1945–2012 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.)

The episode is related in Randall Collins, “Prediction in Macrosociology: The Case of the Soviet Collapse,” American Journal of Sociology 100.6 (May 1995): 1552–93. The original prediction of Soviet collapse was published by Randall Collins as “Long-Term Social Change and the Territorial Power of States,” Research in Social Movements, Conflict, and Change 1 (1978): 1–34.

Читать дальше