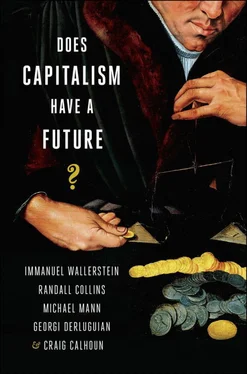

Immanuel Wallerstein - Does Capitalism Have a Future?

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Immanuel Wallerstein - Does Capitalism Have a Future?» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Oxford University Press, Жанр: Публицистика, sci_economy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Does Capitalism Have a Future?

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oxford University Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-19-933084-3

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Does Capitalism Have a Future?: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Does Capitalism Have a Future?»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Does Capitalism Have a Future? — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Does Capitalism Have a Future?», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the end, where do we agree or disagree? We share in common the assessment of our present world situation—including its intellectual and political climate—where we identify the blind spots and therefore the dangers of screwing up in the future. These agreements make up the main body of our concluding statement. But we are not hiding our theoretical differences regarding the ways in which we construe the world and its future prospects. In getting together to write this book, the immediate hope was that our unity as well as our differences would provide for a panoramic vision and a productive debate. The greater hope was that, if we succeeded in getting the attention of sufficiently many readers, we could also make a difference.

We agree that the world has entered a stormy and murky historical period which will last several decades. Big historical structures take time to shift or unravel. The recent Great Recession forces us all to think deeply about world prospects. The central question is not just the prospects for continued American economic dominance and geopolitical hegemony, nor where on the globe such dominance will pass to next, but whether major structural transformation is likely to happen. Although we disagree on some points of the prognosis, there is considerable commonality in our sociological vision. All of us are arguing on the basis of the accumulated scholarship in the realm of macrohistorical sociology—the comparative study of past and present broadly informed by Marxian and Weberian traditions focusing on the structures of social power and conflicts. We are sensitive to multiple dimensions of causality, and tend to agree on many features of how capitalism, state politics, military geopolitics, and ideology operate. Our disagreements are largely about the intersections of different orders of causality: on whether a particular dynamic sector can become so powerful as to overwhelm the other causal spheres, or whether the multicausal world always generates a high degree of unpredictability; and on whether an overarching perspective can display a higher-order system bringing together all the causal sectors into a larger historical pattern.

In this concluding chapter we will first outline the macrosociological way of describing current globalization, its origins and possible futures. The latter part of our conclusion is about social science in its mostly deadlocked present state and its potential for becoming more useful in the immediate future. In other words, we are going to sketch here what we all consider a more realistic picture of the world and the ways of arguing about it.

THE MAKING OF OUR PRESENT

The (so far) Western Great Recession marks the end of the medium-run historical phase that began some forty years earlier, in the crisis of the 1970s. This recent period was confusing enough, as evidenced by a multiplication of misnomers: neoliberal, postindustrial, post-Fordist, post-Cold War, postmodern, postconsumerist, etc. Since the late 1980s, globalization has become the most fashionable generic description of the current world situation. All these names seem to us problematic. Globalization is presented as the grand historical cause of what really were the geoeconomic consequences of the 1970s crisis and subsequent shifts in the world allocation of production processes, or simply what came to be called outsourcing. These labeling dilemmas, however, relate to the fact that the current phase in the long historical trajectory of capitalism has lacked coherence or true novelty. Even the arrival of the Internet, as Randall Collins argues, has revived the old dilemmas of machines displacing human labor and livelihoods. The major condition of the period from the 1970s to the 2000s period was not the emergence of any new structuring forces but rather the undoing of former ones. We mean primarily the exhaustion or extinction of all three Old Left currents: the social democrat and liberal reformism in the “First World” of core Western states; the communist revolutionary dictatorships of rapid industrial development in the “Second World”; and the national populist movements in the Third World.

The past triumphs of the Old Left had flowed directly from the geopolitical upheavals of the twentieth century: not from the abstract march of progress or even the growth of class consciousness per se but directly from the dire experiences of world wars and mobilizations on the homefront that gave opportunity to the peoples, both White and non-White, men and women. In this book Immanuel Wallerstein and Michael Mann, in their own ways, sketch the general lines of this transformation within capitalism, while Georgi Derluguian shows in greater detail what enabled the rise of the communist states and what processes and forces produced their divergent outcomes. The two world wars enormously boosted the long-running trend toward more extensive and invasive modern states. After 1917, in many countries leftist forces suddenly found themselves in a position to capture the wartime state machinery and redeploy its capacities for industrial growth and social redistribution. The intervening Great Depression in the 1930s opened to leftists—but also to fascists—windows of political opportunity by severely discrediting and bankrupting the residual aristocratic monarchies, the oligarchic liberal regimes and their colonial empires of nineteenth-century vintage. The Cold War after 1945 stabilized the results of this epochal transformation for several more decades. The Cold War (another misnomer, actually meaning the “cold peace” of multiple truces and implied diplomatic understandings) institutionalized the internal reformist compromise and welfare provision in the Western democracies, thus containing the specter of revolution long haunting the West. The same Cold War ensured peaceful coexistence with the Soviet bloc, thus containing the old Western specter of war. And by extending international political patronage and economic aid to the former colonies, the Cold War world order channeled the specter of anti-White revolt of colonial peoples into the optimistic and cooperative expectations of universal modernization. Those were the good times of generous payoffs for the trials and sacrifices of wartime decades.

The good times suddenly crashed in the 1970s. Craig Calhoun reminds us that the sequence of another political transition did not start from the resurgent Right. Rather, it was the youthful New Left that first challenged Cold War compromises by demanding still better times minus the official hypocrisies and sclerotic bureaucratism. True, contemporary establishments everywhere—West, East, and South—were showing many signs of bureaucratic pathology and despotism disguised with hypocrisy. Importantly, however, those detested establishments by the 1970s represented later stages of the various political regimes originating in the modernizing, socially reformist, anticolonial, or revolutionary takeovers of the earlier heroic epoch. For all the loudly proclaimed ideological differences, the wartime generation of states held in common their reliance on what the Americans called the triad of Big Government, Big Unions, and Big Business, or their functional equivalents in the Soviet industrial ministries and national republics. All these political and economic structures drew their power and legitimacy from the mass provision of modern education, housing, health and welfare services; typically lifelong industrial employment; and, not least of all, comfortable middle-class careers in the bureaucratic, military, and professional hierarchies.

Certainly many powerless social groups and peoples in different countries felt excluded from this bureaucratically organized prosperity. Typically, these were the racial, religious, immigrant, and gender minorities in the developed countries; the non-Russians and subproletarians in the Soviet republics; and the masses of recent rural arrivals in the sprawling shantytowns of the Third World. But such marginalized groups could rarely raise a political voice. Things would change, however, in the 1960s with the arrival of energetic student activists and dissidents in the intelligentsia spreading organizational techniques along with the ideologies and singable slogans of rebellion against “the System.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Does Capitalism Have a Future?»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Does Capitalism Have a Future?» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Does Capitalism Have a Future?» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.