Immanuel Wallerstein - Does Capitalism Have a Future?

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Immanuel Wallerstein - Does Capitalism Have a Future?» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Oxford University Press, Жанр: Публицистика, sci_economy, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

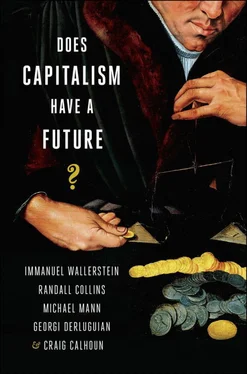

- Название:Does Capitalism Have a Future?

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oxford University Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-19-933084-3

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Does Capitalism Have a Future?: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Does Capitalism Have a Future?»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Does Capitalism Have a Future? — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Does Capitalism Have a Future?», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

ANTI-CAPITALIST REVOLUTION: PEACEFUL OR VIOLENT?

If the crisis of technology displacement becomes severe enough—a highly automated, computerized world in which very few people work, and most of the population is unemployed or competing for menial low-paid service jobs—would there be a revolution?

Here we must leave economic crisis theory and examine theory of revolution. Since the 1970s, the theory of revolution has been revolutionized. Skocpol [1979], Goldstone [1991], Tilly [1995], and others, by their comparative researches on the rise and fall of state regimes, have established what can be called the state breakdown theory of revolution. Successful revolution depends on what happens at the top, not on disaffected and impoverished masses from below. The chief ingredients are: first, a fiscal crisis of the state; the state becomes unable to pay its bills, and above all to pay its security forces, its military and police. State fiscal crisis becomes lethal when it is joined by the second ingredient, a split among elites over how to deal with it. We could add secondary factors, back in the chain of antecedents, typically although not always including military causes; a state fiscal crisis often comes from accumulated military expenses, and elite deadlock is especially exacerbated by military defeat, which delegitimates government and provokes calls for drastic reform. Splits among elites paralyze the state and open the way to a new coalition with radical aims. It is in this power vacuum—what social movement theorists now call the political opportunity structure—that social movements are successfully mobilized. Often they do so in the name of grievances from the bottom, but typically such radical movements are led by upper-middle-class fractions with the best networks and organizing resources. As de Tocqueville recognized long ago, the radicalism of a movement is not correlated with the degree of immiseration; exactly what does determine the degree of radicalism is more in the realm of the ideological and emotional dynamics of exploding conflict, although just how to theorize this remains unfinished.

Virtually all revolutions, up to this point in history, have come not from economic crisis of capitalist markets, but from government breakdown. The key component is fiscal crisis in the government budget itself, but this is usually independent of major crisis in the larger economy. This means revolutions can continue to happen in the future, through the narrower mechanism of state breakdown, the state-centered fiscal crisis, elite deadlock, and ensuing paralysis of state enforcement apparatus. State crises are more frequent than full-scale economic crises. What happens when we put this in the context of the long-term trend to technological displacement of the labor force? Several things are possible: revolutions can happen in particular states, not necessarily those with the greatest amount of technological displacement. Or, revolutions can happen that do not act on a policy of solving technological displacement. But also, revolutions can happen which do take an explicitly anticapitalist turn.

Since history is driven by multiple causes, the future is like rolling multiple dice, as in the Chinese game Yahtzee—waiting for sixes to come up on all five dice simultaneously. Thus we could have the general anticapitalist revolution sometime in the future, through the right combination of state breakdown, perhaps plus war defeat, plus the omnipresent technological displacement.

The crisis of capitalism sets the agenda. At some point the politically mobilized populace will have to deal with it. This could happen by the classic route of state breakdown: the legitimacy of the state is called into question; the state itself stops functioning (paralyzed by fiscal crisis and/or political splits within its own ranks, mirroring political polarization outside); the monopoly over organized violence breaks apart, as police and the military lose organizational coherence and factionalize. This may or may not produce extensive violence, whether in riots and crowd suppression, or in civil war. In some moments of revolution (for instance the French Revolution of February 1848) the period of tense crisis was resolved with relatively little violence, as the existing regime lost organizational coherence, no one wanted to take charge of continuing the existing regime, and a new parliamentary power was quickly constituted. Similarly in Russia in February 1917, after several days of sporadic violence and wavering between crowds and soldiers, the Czarist regime ended in a flurry of abdications and refusals to pick up the reins. These cases also show that in ensuing months and years the new revolutionary regime may have trouble consolidating power, especially when restorationist movements mobilize against it, and later violence is often more severe than the initial revolutionary transition. Separating the revolutionary moment from its aftermath, the process of revolutionary state breakdown need not be very violent. Political sociology has not yet taken up the issue of under what conditions postrevolutionary consolidation of government is peaceful or violent. All we can say is that the range of violence seen in historical revolutions and their consolidation would also be possible in the terminal crisis of capitalism. The most dangerous possibility is that the prospect of anticapitalist revolution, seen by its enemies as the threat of violent change, would give rise to a neofascist solution: an authoritarian regime supported by popular movements nostalgic to save capitalism, which would carry out enough redistribution so that the massively unemployed population would be kept alive, but under a police state constantly on the alert for subversion. We do not know how to estimate the chances of an attempted fascist solution, compared to a democratic postcapitalism. Wallerstein has conjectured that it may be 50–50.

But a favorable alternative may be quite likely: the institutional transformation from capitalism to a noncapitalist system of political economy—an institutional revolution—could come about through peaceful political process. If the crisis of capitalism is severe enough—a majority of the population structurally unemployed, robots and computers doing almost all the income-generating work but owned by a small number of wealthy capitalists, the economy in deep depression—at some point a political party could win electoral power on an anticapitalist program. Some governing party or coalition would have to replace capitalist production, distribution, and finances with a system that redistributes wealth outside the system of labor market and profit-taking.

This kind of electoral politics might seem far-fetched in the political atmosphere on the present—just twenty years after the fall of the Soviet bloc, coinciding with an enormous market expansion in nominally communist China and with the triumph of market ideologies everywhere. But political moods are prone to wide swings every twenty or thirty years: think back through each twenty-year segment of the 20th century. If the structural trend to technological displacement continues to deepen, a vast reversal of opinion another twenty years into the future is not at all unlikely.

A peaceful institutional revolution is possible. The deeper the structural crisis of the middle class, the more mobilization for electoral politics is facilitated. Along that route lies the prospect for a relatively nonviolent transition.

COMPLEXITIES OF HOW STRUCTURAL CRISIS WILL UNFOLD

The world is the product of multiple intersecting causalities. Everything is clothed in particularities of locality, sequence, and memory. Thus the structural crisis of capitalism will have many variations. What is at issue here are not the names, dates, and dramas, but the big dimensions of complication—major processes that can drastically change the nature of the crisis as capitalism becomes too self-destructive to continue.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Does Capitalism Have a Future?»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Does Capitalism Have a Future?» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Does Capitalism Have a Future?» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.