Surrogates, meanwhile, posited far-fetched arguments. Perhaps, they said, Koch himself had traced over the “original” engravings with a drill. Why? Because Koch was “a neurotic maniac.” Rodenstock suggested that Koch was upset because, at the 2000 Latour tasting where the men had had their only meeting, Rodenstock had made a comment to the effect that Koch was a prestige collector, rather than a true connoisseur. Specifically, Rodenstock recalled uttering the expression “the last shirt has no pockets,” the German equivalent of “you can’t take it with you.” Now, he theorized, Koch was avenging that remark. To the glossy society tabloid Bunte, Rodenstock dismissed Koch with a pearl of Bavarian trash talk: “The oak tree is not concerned with the pig that is scratching its back against the roots.”

THOSE WHO HAD vouched for the bottles over the last two decades varied in their responses. Jancis Robinson was quick to put news of the suits on her website, writing that “I should perhaps have smelled a rat,” but pointing out that she had mentioned the questions about the authenticity of Rodenstock’s bottles in a late-1990s newspaper column. Alexandre de Lur Saluces, who in 1986 had called Rodenstock “my friend” and said he saw “no reason to doubt the authenticity” of the Jefferson bottles, now stated that he had always been skeptical of the bottle he tasted in 1985. Winespectator.com, in the awkward position of belonging to someone who owned one of the bottles, stayed silent. Decanter.compublished a story that dealt with the role of Broadbent, despite his being one of its star columnists. Robert Parker’s opinion of the non-Jefferson Rodenstock bottles he drank in 1995 hadn’t changed: “[T]he wines I tasted were great wines—real or fake.” Robinson handled the delicate matter of her old friend Broadbent’s role by not mentioning it in her write-up of the scandal, instead leaving that work to a reader’s post she published on her site. “I knew he’d had a tough time in the [newspaper],” Robinson later explained. “I suppose I was being a bit protective of him.”

Those who had sold the bottles began pointing fingers, all in the same direction. Farr Vintners, which had sold more of the bottles on Rodenstock’s behalf than anyone else, emphasized that it had been a mere conduit. “Our position,” Farr’s Stephen Browett wrote in an e-mail, “is that we made it clear to our buyers at that time that we were not guaranteeing the quality of the bottles and made it absolutely clear that Mr. Rodenstock was the source of them. We just took a commission. At that time the wines had been authenticated by Michael Broadbent of Christie’s who was regarded as the world’s leading expert.” In another e-mail, Browett added, “I don’t think that anyone would have bought or sold these bottles without his expert opinion.”

“Looking back, more questions could have been asked” was the gentle bureaucratese used by Christie’s North America wine head Richard Brierley as he threw his department’s venerable, seventy-nine-year-old chairman emeritus under the bus. The auction house told the Wall Street Journal that Broadbent wasn’t available to comment.

Privately, Broadbent was shaken by the news of the lawsuits, if not enlightened. A few days after they were filed, he said Rodenstock was “an absolute fool for not revealing where he got the bottles,” as if there were still possibly a legitimate answer to that question. In Koch’s lawsuit and the subsequent news coverage, Broadbent saw “an obsessive witch-hunt.”

There was a general sadness among Broadbent’s many admirers, who could not deny that the affair had left him, as one collector put it, “very damaged.” His old-vintage bible, which continued to be quoted from liberally in every new Christie’s auction catalog, was riddled with tasting notes from Rodenstock bottles. Nearly all of the rarest wines, in a book premised on its comprehensiveness and inclusion of wines almost no other living person had tasted, Broadbent had drunk courtesy of the German. Any number of others had been drunk courtesy of friends of Rodenstock, and had likely come from him.

With his 2002 edition of his big book, far from quietly cutting back on the number of notes derived from Rodenstock tastings, Broadbent strewed them throughout. No one collector appeared as often as he, and Broadbent wrote of Rodenstock’s “close friends, among whose number I am lucky to count myself… Hardy is a remarkably modest man, but jealous of his sources, though many of his rare wines have been bought at Christie’s. Through his immense generosity I have not only had the opportunity to taste an enormous range of great and very rare wines, but have met a very wide circle of enthusiasts and collectors, becoming one of the privileged fixtures at Hardy’s events.” Unlike the previous edition, in this one Broadbent included no special appendix delving into the provenance of the Jefferson bottles.

No one was suggesting that Broadbent had had criminal intent, but only that he had put on salesman’s blinders. And again the Hitler diaries came rushing back with their striking parallels. One of the reputations that suffered most in that earlier scandal had been that of the Oxbridge historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who authenticated the diaries. Trevor-Roper’s misguided authentication, however, evaporated in a matter of days. Broadbent continued to insist that the Jefferson bottles were legitimate for more than twenty years, through many Rodenstock bottle sales, innumerable tastings of Rodenstock wines, and multiple editions of his increasingly Rodenstock-reliant book.

“I think he felt vulnerable,” Jancis Robinson said later. “This has been a very important part of what he has done, but I think even today he has been convinced that he has enough evidence.”

And Broadbent wasn’t giving up the fight. Twenty years before, the New York Post had reported that the real buyer of the 1784 Jefferson Yquem purchased by the “teetotaler” named Iyad Shiblaq was Dodi Al-Fayed. Broadbent knew otherwise. Following the 1986 auction, he and his wife had dined with Shiblaq at the Jordanian’s gambling club in London. Shiblaq himself had been the purchaser of the bottle.

Now Broadbent tracked him down and persuaded him to lend his bottle to Broadbent so he could have his own experts examine the engraving. Afterward, Broadbent declared that Christie’s had commissioned the new examination and that “we can confirm that the engraving is exactly correct, French and of the period,” but a Christie’s spokesman disavowed knowledge of the reappraisal, and Broadbent wouldn’t allow independent inspection of the experts’ report. In a chatty fax to Rodenstock in November, Broadbent revealed that the new appraisal had been done by Hugo Morley-Fletcher, the former head of Christie’s ceramics and glass department, who had done the original appraisal of the 1787 Lafite back in 1985; he was now a consultant who served as an expert on the TV program Antiques Roadshow UK . Koch’s team remained confident that the Shiblaq bottle was as fake as all the others.

In January, Broadbent underwent major heart surgery. Afterward, he cut down on his public appearances. When he attended an event honoring a Bordeaux winemaker in London, Jancis Robinson thought he looked “very frail.” In early May he retired from Christie’s board of directors, though he remained a senior consultant to the wine department.

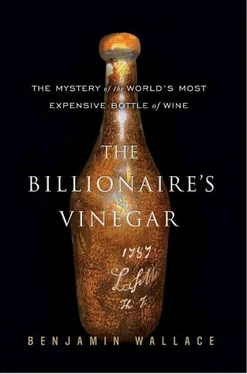

THE RARE-WINE POOL was indelibly tainted. “Whoever’s doing this,” Bipin Desai had said of fakes, the month before Koch filed his suit, “they have to be caught. They’re spoiling the old wine market—slowly, steadily destroying it like a cancer.” Estimates of the number of fakes in circulation were usually given as 5 percent of the market, but ran much higher for certain cult bottles. Suddenly the flashier offerings of some merchants began to seem almost ridiculous. There was the provenanceless 1784 Lafite advertised in the catalog for Christie’s September auction in New York, which the auction house yanked from the sale at the last minute. There was the 1787 Yquem sold earlier in the year by the Antique Wine Company in London to a private American collector for $90,000. Rumors were rife that some collectors were knowingly unloading fakes from their cellars at auction.

Читать дальше