Molyneux-Berry made a point of not wanting to know the source of any bottle before he had made an assessment of its authenticity. He didn’t want to have an unconscious bias. “I don’t want to know the provenance,” he said. “That could color my own opinion. I’m just picking up each bottle, writing down what I think: fake… real… I don’t want to be like a jury told of a prior criminal record.”

In July, Molyneux-Berry took a break from cataloging, flying to Moscow to judge a sommelier competition before returning to the United States to resume his work in the Koch cellars. Molyneux-Berry had left the paper trail to others in Koch’s organization, and as they narrowed down the channels—not easy, given the compartmentalized information structure of the rare-wine market—news filtered back to him that several of the bottles he had deemed fake had come from Rodenstock.

Regarding Michael Broadbent, his old rival, Molyneux-Berry was split. He respected Broadbent’s success and his talent. He thought less of the lengths to which Broadbent was willing to go in order to win. “He told me,” Molyneux-Berry recalled, “‘My major weakness is I’m a salesman. I have to cut the deal.’”

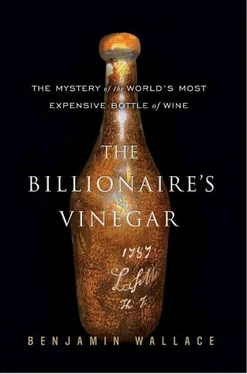

Looking back now on the original Christie’s catalog featuring the bottle bought by the Forbes family, Molyneux-Berry noted that Broadbent hadn’t even mentioned Monticello (Molyneux-Berry had consulted with them first thing upon being offered the Frericks consignment in 1989): “There’s a fear in the way it’s cataloged. I suspect he was sick as a parrot about the authenticity, but he couldn’t resist the opportunity. It was the juiciest carrot he’d ever got.”

Molyneux-Berry wasn’t losing sleep over Rodenstock’s fate, which he thought might be worse than losing a lawsuit. “One or two of these guys are ferocious,” he said, referring to Rodenstock’s Hong Kong customers. “They will chop his head off, not ask for their money back. If we find a torso that looks like Hardy Rodenstock’s, we’ll know they’ve gotten their revenge.”

FOR NOW, AN intact Rodenstock was still making the society scene. In early 2006 he appeared with Prince Albert of Monaco at an event where Rodenstock made a donation to one of the prince’s charities. In May, Rodenstock attended Riedel’s 250th-anniversary celebration in Kufstein. But there were indications that he was getting nervous. In August he reached out to Walter Eigensatz, Mr. Cheval Blanc, who hadn’t spoken to him in years. Rodenstock called him and asked after his health, speaking of the good wines they had shared and suggesting they get together sometime. Eigensatz was measured in his response, leaving Rodenstock with the stark warning that he should “be careful.” It was clear to Eigensatz that Rodenstock was trying to make nice with his enemies. “A year ago he was telling people he hoped I’d die,” Eigensatz said a month later.

Michael Broadbent, pedaling blithely into the gloaming, seemed only mildly concerned by what was happening. “He was reluctant to tell me where he got them,” Broadbent told a guest in late 2005, speaking in Room Number 7 of the London headquarters of Christie’s. The room, its walls lined with red fabric, was one of a suite of tiny, windowless compartments on the ground floor that were reserved for specialists to meet with clients. Broadbent and the visitor were seated at a small square table. The former head of the wine department wore a dark pin-striped suit. Gold cuff links peeked out from the sleeves.

Broadbent’s tasting notes now exceeded 85,000, and he had only two blank red notebooks left. The manufacturer had changed the color to black, but Broadbent didn’t expect to have to make the change. “I’ll be dead by then,” he said. For a seventy-eight-year-old man who had devoted his life to alcohol, Broadbent looked fantastic. His face bore none of the exploded capillaries of the vodka-dependent; his liver functioned properly; his waistline remained in check; his mind was still acute.

“He was reluctant to tell me where he got them,” Broadbent was recalling. “That’s the only big question. And I said to Hardy, I said, ‘Look, if you tell me where you got these, and I’m happy, my Christie’s clients will be happy that I’m satisfied.’” Two decades on, to Broadbent’s unceasing irritation, Rodenstock had still not obliged him.

Broadbent had recently been fielding all kinds of inquiries about the bottles, including one from a woman who ran the New York charity to which Bill Sokolin had donated his broken Jefferson bottle. She had contacted Broadbent in an effort to ascertain its provenance. Broadbent, in turn, had put the question to Rodenstock. On August 21, Broadbent had received a fax from Rodenstock, who had just attended the Salzburg music festival, where he reported that he had had “a lovely time.”

Broadbent had begun to get nervous, as the possible repercussions of a full-fledged investigation began to dawn on him. In a handwritten fax to Rodenstock on October 4, he wrote:

Dear Hardy,

Jefferson bottles. You and I are bored stiff with this subject. Unhappily, more pressure from the USA. I had a huge file, including Frericks, but neither I nor my secretary can find it. I seriously need all the filing you have on the Bonani/Hall analyses, and anything else relevant. It is important that I produce the evidence, again, for your reputation, Christie’s, and mine is at stake.

Warm regards as always, Michael

Rodenstock faxed a reply six days later, saying that he had been contacted by Koch’s investigator. Rodenstock promised to send copies of the before-and-after photos he had presented as evidence in the Frericks case, which he falsely claimed “clearly show that the bottle has been tampered with after it has left my cellar. Frericks certainly had fiddled about with the wine himself. The sealing wax is without any doubt no longer identical with the sealing wax the bottle had when Frericks had bought it from me.”

Now Broadbent’s nervousness seemed to have receded and been replaced by weariness. Talk turned to Sotheby’s, toward which Broadbent’s hostility had hardly abated. “Of course, I hate her,” Broadbent said now of Serena Sutcliffe. “I find her totally pretentious.” He continued, “But the great joy was, Serena is incredibly proud of her lingual abilities. Philippine de Rothschild was having a lunch party in London, and Serena was being over-the-top about something: her father was in the war, and I never had any relations in the war or killed in the war, things like that. She was just being absolutely obnoxious. And Philippine de Rothschild leaned over and said, ‘Serena, I cannot abide the way you speak French.’ And Serena was knocked back.” Broadbent did his best impression of Sutcliffe looking astonished. “And I said, ‘Tell me, what is it about her speech?’ Philippine said, ‘First of all, it’s very pretentious. She’s trying to speak in what she thinks is the French upper-class accent, and she’s using words that went out of favor years ago, and she just misses it.’” Broadbent grinned, clearly enjoying himself.

“I can tell you endless stories about her pretentiousness, silly mistakes she makes,” he said. “But I won’t. But she is very bright. She’s known as Pushy Galore in America. Some American told me that. She is pushy. I mean, she’s a hand-presser, particularly in Bordeaux, and she charms them all, but some people there can’t stand her, either.” He paused. “But she’s done a great deal and put Sotheby’s on the map. Whereas they were lagging hopelessly before.”

The conversation grazed other topics, then Broadbent said, “It’s terribly hot in here. Let’s go and have a drink.” King Street was still slick from the morning rain. The world headquarters of Christie’s was situated in the heart of St. James, a neighborhood of bespoke shirtmakers, old-line wine merchants, and private men’s clubs dating to the time of Britain’s seventeenth-century glory.

Читать дальше