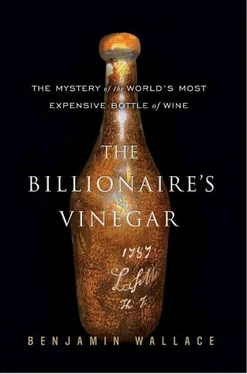

NOT LONG AFTER David Molyneux-Berry had turned down Frericks’s cellar on behalf of Sotheby’s, the Munich businessman had consigned it to Christie’s. When Rodenstock subsequently learned about it, he insisted that he had sold bottles to Frericks on the condition that they would drink them together and with the understanding that they weren’t for resale.

Alleging that he had sold Frericks the Jefferson bottles at a “friendship price” and strictly for the purpose of a Lafite vertical to which he, Rodenstock, was to have been invited, Rodenstock persuaded Broadbent to postpone the sale of the Frericks cellar. Frericks responded by obtaining a court order, issued on December 4, 1990, enjoining Rodenstock from publicly claiming that they had had such an agreement, on penalty of 500,000 marks or six months in jail. Rodenstock appealed the injunction, but later withdrew his appeal.

In the meantime, Frericks, now acutely suspicious, pulled his bottles from Christie’s and began telling anyone who would listen that Rodenstock’s objections to a resale must be due to the bottles being inauthentic. The two men traded accusations in Munich’s tabloids. Frericks suggested that Rodenstock himself had tampered with the bottles. Frericks considered having the wine scientifically analyzed, but hesitated before doing so. If his suspicions were wrong, he would be destroying an irreplaceable historical artifact that had cost him a lot of money to buy. Ultimately, however, he resolved to have one of the two Jefferson bottles tested by GSF. Rodenstock then turned the tables by producing before-and-after photos purporting to show that the seal on the bottle when Rodenstock sold it to Frericks in November 1985 was different from the seal on it now, and that the corks and ullage had changed as well. On July 15, 1991, Frericks swore in court that “[a]t no time did I alter the bottle… I never had the bottles resealed or sealed.” Four days later, on the outskirts of Munich, he and Broadbent came together to open it.

At GSF, Broadbent held the bottle in front of a candle: the sediment looked authentically old. Manfred Wolf, a bearded chemist in a short-sleeved shirt, poured two-thirds of the wine through a funnel into a glass container for analysis. Broadbent splashed a small amount out of the Jefferson bottle into a wineglass. Holding a sheet of white paper out as a backdrop, with Frericks looking on, Broadbent tilted the glass sideways against it, the wine becoming a wider, shallower, more translucent pool. He peered through his half-moon reading glasses. The brownish hue indicated great age. Broadbent sniffed, then sipped. The nose and palate, too, suggested an ancient wine. It tasted, Broadbent said, like the Mouton opened five years earlier at Mouton. He felt relieved. It remained only for the scientists to confirm his sensory impressions.

For much of his career, Broadbent’s eminence as a taster had owed nothing to Rodenstock. In 1980 the Christie’s auctioneer had published his magnum opus. The Great Vintage Wine Book was an encyclopedia of tastes, a compendium of notes on every wine that had passed Broadbent’s lips since he first began jotting down his impressions in 1952. The oldest red Bordeaux he had tasted, and the only one from the eighteenth century, was the 1799 Lafite he had tasted one year earlier at Marvin Overton’s vertical in Fort Worth. He had tasted no big-bottle Pétrus older than 1945. The oldest Yquem dated to 1867. There were no notes from Rodenstock tastings, and the German’s name did not appear in the book.

By the time Broadbent updated the book in 1991, his reputation had become wholly entwined with Rodenstock’s. Nearly all of the oldest and rarest bottles he had tasted, from a 1747 Yquem to a 1771 Margaux to the Jefferson bottles to a series of prewar Pétrus in large formats, were supplied by Rodenstock, whose tastings Broadbent had attended annually starting in 1984. In this edition, Broadbent said he had now tasted “one thousand wines” at Rodenstock tastings, and, with the GSF results pending, felt the need to include an appendix laying out his old case for the Jefferson bottles’ authenticity, as well as retailing Rodenstock’s claim that he “was not aware of the significance of the initials T.J. until the first bottle (of the 1784 vintage) was opened at Château d’Yquem.”

In the six months after the opening at GSF, Broadbent would also fly twice to Bordeaux to see the printer of the labels on the large-format Pétrus bottles that had been at the center of much of the skepticism about Rodenstock. The wines dated from as far back as the 1920s, but the printer named at the bottom of the labels, Imprimerie Wetterwald Fréres, was still in business. On the first visit, Broadbent took along a double magnum of Pétrus 1945 that had come from Rodenstock, and a regular bottle of Pétrus 1945 from an unspecified “impeccable source.” The bottles had different labels, but the printer explained to Broadbent that while offset lithography was used for regular-size labels, a different method was used for larger ones. Broadbent came away believing the double-magnum label to be “genuine.” He next returned to Bordeaux with a double magnum of Pétrus 1921 from Rodenstock. “Wetterwald and his printers looked at it through magnifying glasses and pronounced it correct,” Broadbent wrote later. If the GSF tests on Frericks’s Jefferson bottle went as well, maybe the whole controversy could finally be put to rest.

ON THE DAY of the test in Munich, Yeter Göksu, standing near Broadbent, had taken a sip of the wine and thought it tasted horrible—sweet and insipid. In her opinion, only an idiot would buy this wine for so much money. An elegant Turkish-born physicist in her forties, with black hair and green eyes, Göksu had recently been conducting experiments on whether food irradiation, the practice of zapping food with gamma rays or electron beams to extend its shelf life, had negative health effects. She had been focusing mainly on dried spices.

Half a liter of the wine in the Frericks bottle went to Wolf, the chemist, who worked in a different branch of the institute; Göksu got the dregs. She would use thermoluminescence, the same technology with which she analyzed irradiated cumin, to date the sediment. Her lab was a suite of rooms in a massive building across the road from her office. They were kept cool and lit by a dim red bulb. If the materials to be studied were exposed to light, it would contaminate the signal they yielded; it was the wine’s purported history of containment in a dark bottle in a dark cellar that allowed it to be dated now by thermoluminescence.

In her lab, Göksu first poured out the five centimeters of liquid remaining in the bottle. Half she set aside for two other scientists to work with; the other half she would analyze herself. Then she turned the bottle upside down to shake out the sediment. A flat, rectangular object with a reddish, coppery hue clunked out onto the table. This was strange. What was a piece of metal doing in the bottom of a two-hundred-year-old bottle of wine? She gave it to some colleagues, Bernhard Hietel and Friedrich Schulz, who operated a linear particle accelerator elsewhere on the campus.

Their specialty was bombarding objects with a high-speed beam of protons fired down a barrel that began in one room and went through a wall into another. By measuring the wavelengths of the energy thrown off by the collision, the physicists could determine the constituent elements of the target. The piece of metal was, as they suspected from its appearance, solid lead. They next bombarded some of the wine itself to see how much lead was in it. Their test showed 11.3 milligrams of lead per liter, a toxic concentration. But this was inconclusive, as other nineteenth-century control bottles, which didn’t have pieces of lead resting in their sediment, also showed a lead content five times as high as some bottles of Bordeaux from the 1980s. To the two men, the lead appeared to be a piece of the protective foil “capsule” that envelops the mouth and neck of modern wine bottles.

Читать дальше