“Is Rodenstock a poseur, a cheat?” Broadbent asked rhetorically in a letter to Rarities. “Deceitful or just ingenuous? Plausible certainly, a little worrying perhaps. But to suggest that every marvelous tasting old bottle, or strange and ‘off’ bottle, is the result of his manipulation is distinctly unfair and, I believe, wide of the mark. But I wish he would be less secretive. It merely adds to everyone’s suspicions.”

A divide was opening around Rodenstock’s bottles. Depending on where you stood, it was either a substantial factual disagreement or a philosophical schism. The L. A. contingent, for the most part, deemed atypical bottles to be suspect, prima facie. Rodenstock and Broadbent argued that such bottles were illustrative of the very diversity they found thrilling in old wines. In this view, almost any flavor, no matter how weird, could be explained away as an artifact of some unknown circumstance in a wine’s maturation (storage conditions, say, or bottle variation—a truism about mature wines is that there are no great wines, only great bottles).

Insiders’ skepticism seeped into the wider wine world’s consciousness, as the leading wine magazines began to sneak occasional snide asides into their copy. In December 1987, Decanter reported a record price paid for a Jéroboam of Pétrus 1961 ($14,000), attributing it partly to the wine’s “rarity following a burglary at the château. Christie’s say they know of no other Jéroboam, so this was probably a unique chance for a wealthy buyer (unless Mr. Hardy Rodenstock of West Germany happens to have a cache). As far as is known, Thomas Jefferson did not buy this wine.”

Two years later the Wine Spectator published an April Fool’s account of a $5.7-million bid for a “red wine believed to have belonged to Julius Caesar.” The spoof went on to say that “[t]he ancient clay amphora, which bears the initials ‘J.C.,’ was found in a bombed-out cellar in Beirut, Lebanon, by well-known West German collector Hardy Rodenstock.” Moreover, Michael Broadbent had “verified the amphora as genuine” and stated that “[i]t may well be [drinkable]…. Only last year I tried a 2,100-year-old red wine from Crete. Although the color was somewhat faded and the flavors had dried out a bit, it still retained a delicate bouquet of pine resin, ancient Roman sandals, and Minoan bull droppings.” Rodenstock had been raising eyebrows for some time, but open mockery of the venerable Broadbent was something new.

The effects of the creeping cynicism on the rare-wine market were more serious, as auction houses experienced a softening of demand for old wines. At a June 28, 1990, sale at Christie’s London, only a few of the dozen nineteenth-century Bordeaux on offer sold.

The doubts caused rifts in Rodenstock’s inner circle, even before Walter Eigensatz became disillusioned. In 1987, Mario Scheuermann, the Hamburg journalist who had known Rodenstock since the late 1970s and had been to every one of his big tastings, attended the first Masters of Food & Wine event in Carmel, California. There, everyone asked him about rumors that Rodenstock’s bottles were fakes. Upon his return to Hamburg, Scheuermann called Rodenstock and told him what people were saying. Rodenstock reacted angrily. Scheuermann responded that he was just the messenger, but Rodenstock wasn’t pacified. He stopped speaking to Scheuermann. And once Eigensatz began openly expressing doubts about his bottles, Rodenstock several times threatened to sue his former friend.

Rodenstock increasingly alienated people in Bordeaux, with both his dispute with Lur Saluces and another campaign he waged against Christian Moueix, the young head of Pétrus who had publicly doubted Rodenstock’s big Pétrus bottles from the 1920s. This time his target was Moueix’s use of filtration, a controversial modern technique for clarifying wine before bottling. Rodenstock presented himself as a defender of tradition, and Bordeaux winemakers such as Lur Saluces and Moueix as destroyers of it.

Rodenstock’s personal elusiveness was now writ larger. He moved among his many homes, communicating mainly by fax, as he continued to solicit new clients. In 1989, when Adnan Khashoggi, the Saudi arms dealer who was Dodi Al-Fayed’s uncle, was briefly imprisoned in Berne, Switzerland, Rodenstock told people he had sent him a bottle of Pétrus and that, after his release, Khashoggi had placed a large order with him.

There was a sense of innocence lost among the German collectors. “In the beginning, we were all friends, interested in what each next wine would reveal, be like,” Frenzel said later. “There was a wonderful sense of camaraderie. The problem was, when the newspapers wrote stories, then came jealousy and competition. The tastings became bigger, there were more journalists, who were more and more competitive with each other. There were more people who weren’t into wine but were there for their image and the glamour. And then the women started coming to the tastings in 1989 or 1990, which made it worse. They brought out the worst qualities in their husbands: ‘Oh, you have a big watch, mine’s bigger.’” Frenzel thought it was the appearance of the big profile of Rodenstock in Wine Spectator, with its cover photograph of him chomping on a cigar, that turned many of his friends against him.

What had earlier been a sense of playful competition was now more acrimonious. Collectors who contributed rare bottles that showed badly resented Rodenstock’s bottles, which always seemed to come out smelling like roses, and spread rumors that the bottles must be rigged. “It’s the kindergarten syndrome,” Scheuermann said. “The five children in the sandbox won’t let the sixth in.” But none of the rifts was as public and bitter, or had farther-reaching repercussions, as that with the man known as Herr Pétrus.

HANS-PETER FRERICKS lived in a southern suburb of Munich, not far from where Rodenstock had moved after leaving the tiny Westerwald town of Bad Marienberg in 1985. Frericks had gotten rich selling bicycle and car accessories, such as windshield wipers, in supermarkets. When the German government passed a law in 1988 requiring that every car contain four pairs of PVC “anti-AIDS” gloves in their glove compartments for first-aid purposes, Frericks made a killing. He had anticipated the legislation and filled a warehouse with the gloves.

Despite his vaunted enthusiasm for Pétrus, some of his fellow German collectors viewed him as more of a status drinker than a serious wine person. Bearded and shiny-domed, Frericks was wont to get loud and drunk, and he once posed for a magazine photographer in a restaurant kitchen wearing an apron with nothing underneath, buttocks exposed. By the end of the 1980s, his interest in wine was waning, and in 1989, Frericks decided to dispose of a substantial portion of his cellar. He asked Sotheby’s to handle the sale. The head of the auction house’s wine department, at the time, was David Molyneux-Berry, whose habitual look incorporated a bow tie, glasses, Vandyke beard, and ponytail. He had been with the department since its founding in 1970, and had recently become director. Broadbent, competitive as ever, later recalled Molyneux-Berry as “something and nothing, really… When I knew him when we were both at Harvey’s, it was just David Berry. He became Molyneux-Berry when he went to Sotheby’s.”

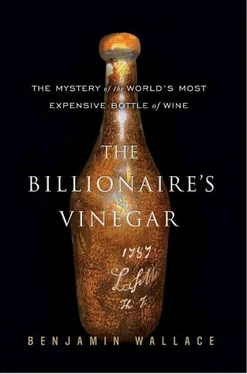

Molyneux-Berry took Count Heinrich von Spreti, who would later become head of Sotheby’s Germany, along to translate, and they drove to Frericks’s villa. In the cellar they found astonishing rarities, including two Jefferson bottles, a 1784 Lafite and a 1787 Lafite. Rodenstock had sold them privately to Frericks shortly before the Forbes auction revealed how high a price the bottles might fetch, and Frericks had paid only 15,000 and 12,000 marks respectively (equivalent to around $5,100 and $4,000).

Читать дальше